Lorem ipsum •

Paul McCartney v. Fela Kuti •

Profanity •

Fascist haircuts •

September 18, 2001 PIG LATIN Don’t believe the type.

Don’t steal my tattoo idea. Before you read any further, say it aloud: I promise not to steal Todd’s tattoo idea. Okay, I trust you. Here it is: a couple words on my right shoulder or forearm, set in Hoefler & Co.’s elegant Gotham, if the tattoo artist can get it right, and a simple phrase: Lorem ipsum. Maybe, if I’m feeling up to it, the fuller Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. If you’ve had any exposure to design with type, you know the phrase—placeholder nonsense that shows you how the real text will flow once you’re getting ready to publish it. (A Google Image search reveals I’m already late to this tattoo idea, of course. If you ever have a brainstorm, stay away from Google.)

Don’t steal my tattoo idea. Before you read any further, say it aloud: I promise not to steal Todd’s tattoo idea. Okay, I trust you. Here it is: a couple words on my right shoulder or forearm, set in Hoefler & Co.’s elegant Gotham, if the tattoo artist can get it right, and a simple phrase: Lorem ipsum. Maybe, if I’m feeling up to it, the fuller Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. If you’ve had any exposure to design with type, you know the phrase—placeholder nonsense that shows you how the real text will flow once you’re getting ready to publish it. (A Google Image search reveals I’m already late to this tattoo idea, of course. If you ever have a brainstorm, stay away from Google.)

Lorem ipsum is already my personal, private joke. Over the years, I’ve ordered a number of shirts from Blank Label, an online store that applies your measurements to sort-of-custom fits, and I’ve taken advantage of the site’s option to let you dictate your own label. I now own about a dozen shirts that say Lorem Ipsum inside the collar, and only I know it’s there, and I still think it’s funny.

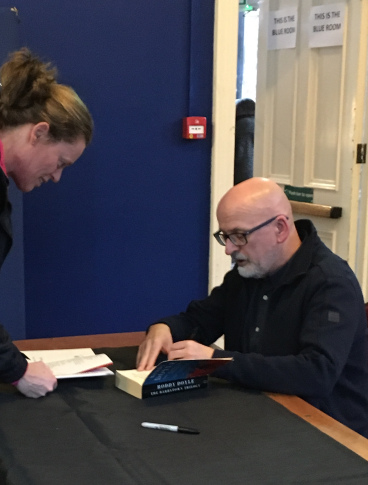

But there’s real intrigue to lorem ipsum. A Latin scholar would know right off the bat that it’s not real language. It recently occurred to me to feed the fake text into Google Translate, until I found a brief 2015 essay in Open Culture explaining its origins as typesetting gibberish. A printer several centuries ago grabbed a page within reach and set placeholder type based loosely on Cicero’s “De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum” (“On the Extremes of Good and Evil”), rendering it illegible so it wouldn’t be published accidentally.

The printer had the right idea. I’d rather let lorem ipsum slip into view than most other alternatives. Deadspin last month published “The Fallout from Sportswriting’s Filthiest Fuck-Up,” a poignant and excruciating history of the worst typographical error imaginable: a paragraph of juvenile profanity that snuck into print and destroyed the reputations, careers, and even lives, of those ensnared in the small-town scandal. Caveat emptor.

ROCKSHOW Chaos and creation. Tuesday night, I saw Sir Paul McCartney, who’s 75, play a live show for the second time in my life, with my sister, who also saw him for the second time, and our mom (fifth time) and dad (sixth). My mom is two years younger than Sir Paul; my dad, five years older. It would have been easy enough and fully understandable for Sir Paul to execute a set list dripping in indulgent nostalgia, and though there was no shortage of hits, he took some daring detours into what I assume were more personal favorites: “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “Junior’s Farm,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Here Today.”

Tuesday night, I saw Sir Paul McCartney, who’s 75, play a live show for the second time in my life, with my sister, who also saw him for the second time, and our mom (fifth time) and dad (sixth). My mom is two years younger than Sir Paul; my dad, five years older. It would have been easy enough and fully understandable for Sir Paul to execute a set list dripping in indulgent nostalgia, and though there was no shortage of hits, he took some daring detours into what I assume were more personal favorites: “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “Junior’s Farm,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Here Today.”

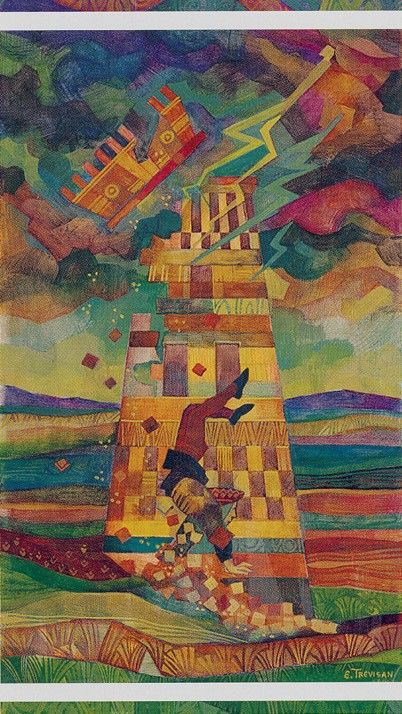

The lineup heavily represented Wings, particularly Band on the Run, and I found myself wondering about the album’s chaos and creation. The band recorded it in 1973 in the restive environment of Lagos, Nigeria, then under the sway of oil revenue, military rule, and the funk-cult bandleader Fela Kuti.

I can imagine Fela feeling wary of a wealthy English rock star coming to town and encroaching on the African Shrine, Fela’s ramshackle club: an opportunity, possibly, for cultural theft. But Paul and Fela quickly sorted out any misunderstandings. No collaboration seems to have taken place, and I’ve never detected the slightest hint of Fela’s serpentine funk on Paul’s album. But 40 years later, in 2013, in a brief interview timed to the release of the tribute album Red Hot + Fela, Sir Paul recalled how Fela’s initial wariness yielded to bonding. It’s a charming story, probably largely unknown to or forgotten by most fans of either superstar. And Sir Paul’s recall in the interview of Fela’s live keyboard riff is astonishing, especially when he sits down to play and sing it from memory.

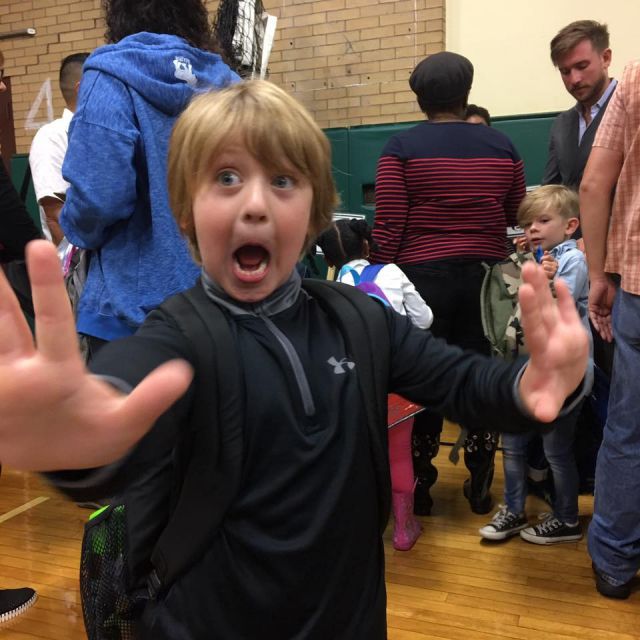

ON LANGUAGE Do solemnly swear. Years ago, as an editor at Details and the father of a newborn girl, I briefly tried to assign a counterintuitive essay about the charms of teaching your kid to swear. I knew a number of dads who could turn a phrase and spin a funny yarn about their darned kids and their darned mouths. I might have gotten the idea from a story Neal Pollack had told about he and his wife both struggling not to collapse into laughter when his six-year-old son experimented (and hit paydirt) with “dammit.” The Details essay never happened, and I didn’t understand it: who wouldn’t find it hilarious to hear a six-year-old swear?

Years ago, as an editor at Details and the father of a newborn girl, I briefly tried to assign a counterintuitive essay about the charms of teaching your kid to swear. I knew a number of dads who could turn a phrase and spin a funny yarn about their darned kids and their darned mouths. I might have gotten the idea from a story Neal Pollack had told about he and his wife both struggling not to collapse into laughter when his six-year-old son experimented (and hit paydirt) with “dammit.” The Details essay never happened, and I didn’t understand it: who wouldn’t find it hilarious to hear a six-year-old swear?

Well, I wouldn’t. Now that I have a six-year-old son who I’m sorry to say gets a genuine reaction from busting out certain four-, six-, and 12-letter-words, I can understand why I wasn’t getting any traction. A situation with a kid who likes getting profane at home wasn’t going to end well if he decided to test-drive his vocabulary in class. (We didn’t have this problem with his older sister. So far, we still don’t.)

I warn him at every opportunity of the consequences of using this language out of context, and he seems to take the point. But on this point, Rachel and I are terrible enforcers. A couple weeks ago, he started belting out the forbidden words while we were driving, and when we grownups in the front failed to contain ourselves, the resulting laughter eventually required a car repair. (I’d say more but I don’t want to jeopardize my insurance policy.) So why don’t parents think it’s charming to let their kids swear? Now I know. And where does he learn this language, anyway? No fucking clue.

INSTAGRAM Fascism week. So far this summer, on the streets of Manhattan, I’ve spotted exactly one MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN trucker cap, worn by a 60something guy dressed in a tourist’s golf shirt and khakis and a defiant pout. And I’ve spotted exactly one TRUMP T-shirt, on an anxious-looking 12-year-old kid with anxious-looking parents, adrift somewhere a block or two from the safe embrace of Times Square. If you spend time anywhere further from Manhattan (or closer to Trump Tower) than I do, your mileage may vary.

So far this summer, on the streets of Manhattan, I’ve spotted exactly one MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN trucker cap, worn by a 60something guy dressed in a tourist’s golf shirt and khakis and a defiant pout. And I’ve spotted exactly one TRUMP T-shirt, on an anxious-looking 12-year-old kid with anxious-looking parents, adrift somewhere a block or two from the safe embrace of Times Square. If you spend time anywhere further from Manhattan (or closer to Trump Tower) than I do, your mileage may vary.

I don’t know for sure that these were tourists, but that’s the only sensible explanation. I’m willing to write off the occasional inadvertent provocation of a clueless visitor who has no idea his cap or shirt would be deeply offensive to the average New Yorker. But I confess that when I witnessed an unambiguously fascist haircut on a young man in J. Crew-catalogue foppery yesterday, my shoulders tensed. The guy might as well have been wearing an armband. Regardless of whether he’s hip to the Richard Spencer connotations—I didn’t ask—I know that nobody happens innocently upon the “fashy” in a GQ spread and then brings a copy of the magazine to the barbershop. It seems impossible to wear this haircut in Midtown Manhattan, on the way to an office job, without knowing exactly what it says.

Unrelated: if you squint at this coif, you could imagine it on Kim Jong-un, and that’s my flimsy excuse for recommending Evan Osnos’s startling report from Pyongyang in The New Yorker this week. Of all the incredible details in his article, the one that amazes me most is that Osnos, an American and a journalist, got North Korea’s clearance to report the story in the first place.

PERSONAL HISTORY Insistence.The anniversary came and went. Given the real-time disasters unfolding this year, and the asymmetry of September 11, 2017, being the 16th anniversary and not the 15th or 20th, it passed with little fanfare. I had my own evil experience with September 11, 2001—everyone in New York at the time did; everyone everywhere did—and we all encountered it in our own way. I spent that day in subdued shock, of course. I walked from Midtown up to my sister’s apartment on the Upper West Side, my back turned to downtown. The first acquaintance I encountered on the street was Ben Katchor, the MacArthur-winning illustrator, who lived across the street from Tracy. I’d interviewed him a few months earlier for the Toronto Globe & Mail. We managed our hellos, and he managed to point out what a beautiful day it was, and then we both ran out of words, standing there on the corner of 102nd Street and Broadway, shaking our heads in a daze.

I was still feeling out of it two days later, on September 13, when Jason Adams and I reacted to a bomb threat at Grand Central by leaving our office at Blender magazine and hoofing it from Bryant Park back to Brooklyn, talking our way past every police checkpoint—14th Street, then Houston, then Canal—until we were right there: enveloped in the silent afternoon, not saying a word as we wove through downtown streets full of jagged concrete slabs and crushed cars and fire engines coated in gray dust.

One of the most vivid documents of that week, one I still re-read, is “Ago,” a small-batch blog post my friend Jason Cochran published seven days later. It’s still every bit as raw now, eerie and prescient, and it never fails to flood me again with those same buzz of dread and nausea, or the feeling Jason identified as insistence:

In one 90-minute stretch, some 5,000 souls were violently unleashed from their bodies, and it happened a little over a mile from my bedroom. The feeling of insistence, I believe, was them. The recently deceased, you often hear, find themselves confused about their new state. The World Trade Center people were telling me that they couldn’t understand what had happened to them. It had happened so quickly, without preparation. They were confused, and they felt lost. It was almost as if they were trying to get my attention for some confirmation.

More next time.

If you would rather get these posts by email, you can sign up here.

Advertisements testify!