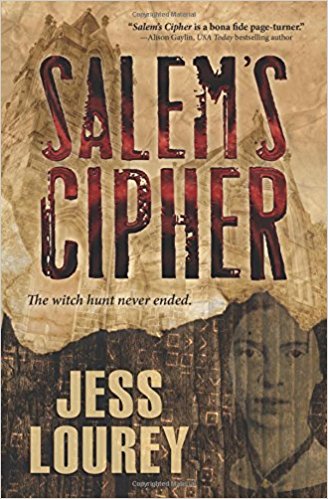

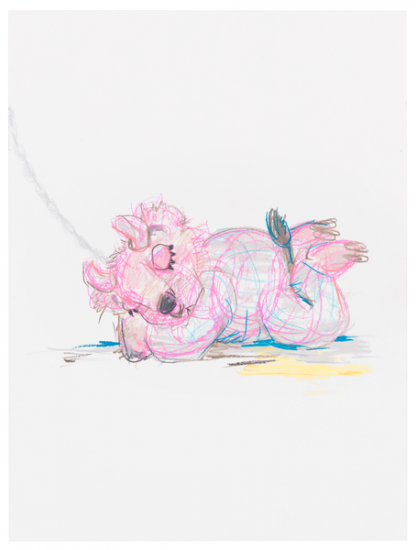

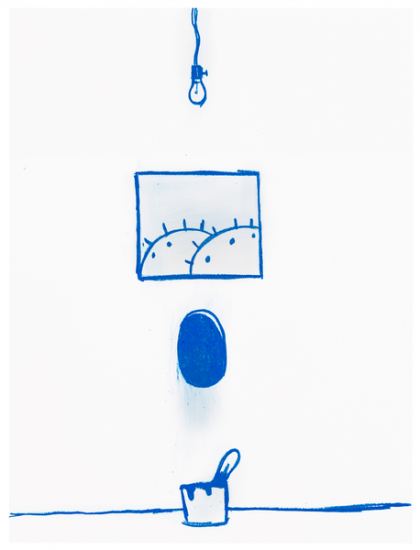

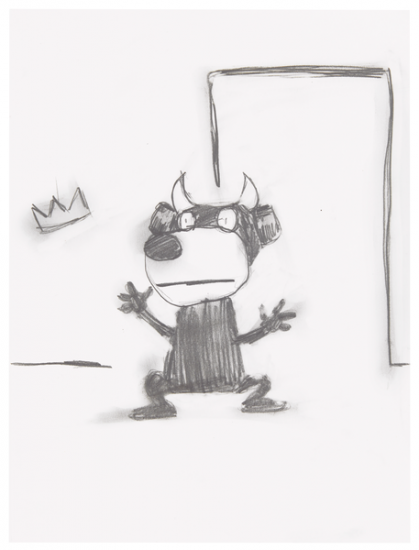

Nayland Blake, 3.8.15, 2015, Colored pencil on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

“The art life is…it’s just another way of saying the great life”–David Lynch

“Writing & Drawing Are Sister Arts,” announces banners flowing from an old-timey quill pen on a drawing in Nayland Blake’s solo exhibition #IDrawEveryDay at Matthew Marks Gallery. Even though this proper illustration, culled from a book of 19th century penmanship exercises, seems at odds with the bulls, bears and bunnies in the surrounding drawings, the work, titled 6.1.15, acts as the show’s manifesto. As with the sister arts of writing and drawing, Blake reveals how daily drawing practice can record a visual memoir of queer experiences, fantasies and possibilities.

While drawing may seem different from a secret diary under lock and key, it still records experience whether real or imagined. In Ann Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings, she looks to the memoir as an essential genre for preserving queer histories and feelings. She writes, “Memoir has potential to explore emotional terrain that is harder to get at through interviews; the sanctuary of writing, its privacy and deliberateness, potentially offers an arena for emotional honesty that is different from the live performance of an interview” (210).

Nayland Blake, 6.1.15, 2015, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

Like the memoir, drawing can be a private, deliberate practice that can form an archive of, as Cvetkovich describes, “ephemeral and unusual traces” (8). Except that in 2017, this visual diary can be shared on numerous social media platforms. Beyond the painfully curated lifestyles, branded content and constant abuse from a wacked-out president, social media has pioneered a certain type of visual memoir–memoirs no longer have to be beholden to the written word. Despite the continued prevalence of photography, hashtags like “#Inktober” also offer communal challenges to pursue ongoing drawing practices. Never has the art life, as Lynch promotes, been so readily accessible and encouraged.

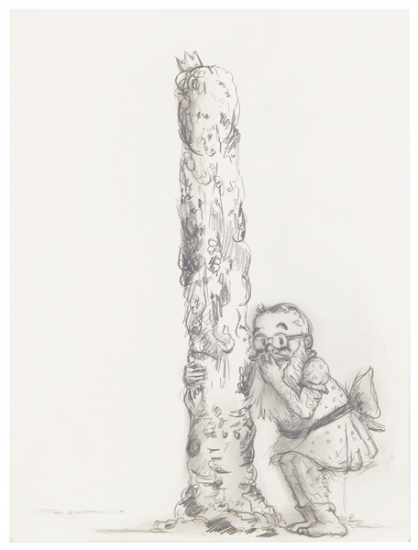

With this in mind, it should be no surprise that the title of Blake’s exhibition at Matthew Marks is a hashtag. Starting on January 15, 2015, Blake began to create at least one drawing a day. Many of these drawings have been posted on the artist’s own social media accounts. While Blake’s interdisciplinary artistic practice is diverse and wide-ranging, their drawings have always been a favorite of mine, namely their cartoonish creations posted to Instagram (and for a limited time, Hyperallergic) that feature Blake’s exploits with a crown-adorned potato friend. They’re hilariously sweet buddy comedies.

Installation view of Nayland Blake’s #IDrawEveryDay at Matthew Marks Gallery (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

Moving off social media into a gallery space, #IDrawEveryDay offers a different viewing experience than mindlessly scrolling through IG. With over 70 equally sized drawings, plus one sculpture, being confronted with such prolific artistic creation is staggering. Each titled for the date of their creation, Blake’s drawings make up a never-ending diary hung on a white wall.

Many of the drawings feature self-portraits of the artist, ranging from sketchy yet realistic likenesses to adorable caricatures. Similarly, some works are more reflectively somber, while others feature jokey visual puns. Take, for example, one drawing that presents a sign stating, “Just When It Gets” behind a hole in the ground from which a speech bubble emerges, “Good.”

Nayland Blake, 9.21.15, 2015, Colored pencil on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

This cartoonish drawing, reminiscent of old Warner Bros. animation and other vintage cartoons, reveals Blake’s interest in so-called (and I hesitate to even perpetrate this but I’m coming to a point) “low” art forms. Throughout their career, Blake has deftly merged queer subcultures, from leathermen to bears, with the pop aesthetics of comic books, stuffed animals, action figures, animation and cartoons. In #IDrawEveryDay alone, many of the drawings feature the recognizable thick, strong lines that look as if they came straight from the pages of Krazy Kat.

Blake isn’t the only queer thinker who sees the possibilities of this “low” aesthetic. In their The Queer Art of Failure, Jack Halberstam insists on the importance of the under-appreciated, as they quote Lauren Berlant, “silly archive,” which allows for “unexpected encounters between the childish and the transformative and the queer” (19-20). Not only donning the style of vintage cartoons and comics, Blake’s emphasis on drawing also resurrects an artistic medium that has historically been viewed as a lesser art. But, as Halberstam insists, “I believe…in the small, the inconsequential, the antimonumental, the micro, the irrelevant. I believe in making a difference by thinking little thoughts and sharing them widely” (21).

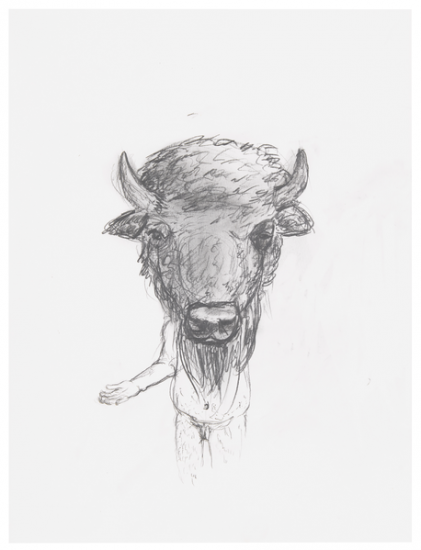

Nayland Blake, 11.11.15, 2015, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

By gathering together a selection of these daily drawings, certain patterns emerge even though, from a lone bottle of what looks like poppers to two trash cans, their subjects are eclectic. Like their interest in comics and animation, some of the imagery in #IDrawEveryDay directly correlates to other aspects of Blake’s artistic practice. For example, a few drawings such as 3.8.15 and 11.11.15 depict Gnomen, Blake’s bison-bear “fursona,” which has since come to life in the New Museum’s Trigger: Gender As A Tool And A Weapon.

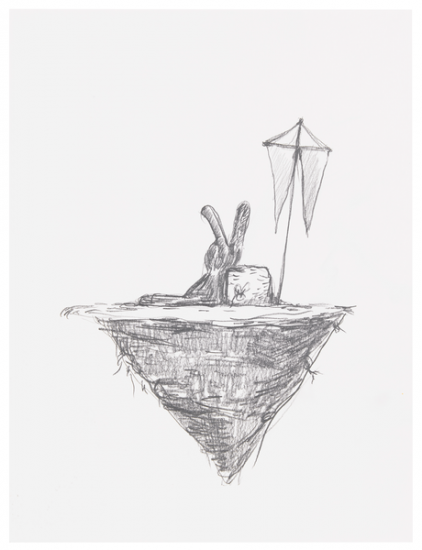

Similarly, bunnies emerge as a theme in the exhibition too as they have in Blake’s art since the 1990s in works like the Heavenly Bunny Suit. For example in the drawing 4.17.16, the silhouette of a rabbit floats adrift on an isolated island–a personification of rootless depression. As curator Maura Reilly describes in a blog post for the Brooklyn Museum, “Blake’s “bunnies” reference complex personal and social narratives about gender, sexual identity, and the artist’s own mixed race heritage.” In fact, both Gnomen and the bunnies reflect a furry form of hybrid identities.

Nayland Blake, 4.17.16, 2016, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

In An Archive of Feelings, Cvetkovich sees “cultural texts as repositories of feelings and emotions, which are encoded not only in the content of the text themselves but in the practices that surround their production and reception” (7). Like Cvetkovich articulates, Blake’s continual drawing practice allows for these complex amalgamations of identity to be reconfigured on a daily basis. One day can bring 3.8.15 with a pink sleepy Gnomen, linked to a chain extending off the page, while another can introduce a self-portrait of Blake wearing a billowy dress while carried romantically and tragically to the edge of a cliff by a bear. Drawing allows for a reinterpretation of the performance of identity, as well as a refusal to be tethered to mundane everyday reality and its restrictions on the possibilities of gender and sexual embodiment.

Even the exhibition’s singular sculpture Untitled seems to reference the fluidity of identity. A ruby red and pink assemblage featuring satin ribbon and leather, Untitled weaves together stereotypically gendered masculine and feminine materials to construct a thoroughly queer whole.

Nayland Blake, 1.26.15, 2015, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

By mirroring the fluidity of identity through an ongoing practice, Blake’s #IDrawEveryDay portrays the complexity of queer lived experience. In their essay “Queer Conversations: Old-Time Lesbians, Transmen and the Politics of Queer Research” in Queer Methods and Methodologies, Catherine J. Nash describes a similar multiplicity of queer perspectives. “Queer perspectives,” they explain, “assert a view of reality as fragmented and multiple and reject explanations that are grounded in the presumption of a directly knowable brute reality” (132).

Blake’s #IDrawEveryday allows for a similar glimpse into these multiple and fragmented realities. Nash goes on to assert, “Knowledge is therefore understood as partial, local and situated rather than capable of being woven into an over-arching grand narrative incorporating the entirety of possible human experience.” (132).

Nayland Blake, 6.15.16, 2016, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery)

Like Blake’s drawings–or Cvetkovich’s explored memoirs for that matter, these queer recorded personal histories, whether visual or linguistic, embrace complexity and contradictions. It isn’t easy to make an all-encompassing description of the exact subjects of #IDrawEveryDay and thank god for that. Instead, Blake embraces the chaotic mess of, as Nash observes, “possibilities and potentialities for lives lived in incongruent and conflicting relationships with normative systems of meaning–neither within nor without–but as a form of fluidity–a mobile instability in experiences, behaviors and practices of the self” (132). Blake echoes this sentiment in the press release, noting, “Drawings allow for internal contradiction. They can be something one minute and something else the next.”

Share this: