Raymond Chandler wrote his first novel relating the adventures of Philip Marlowe in 1939. For those that have forgotten, it was titled The Big Sleep and, as one review described it, The Big Sleep is an unavoidable masterpiece of modern literature. Over seventy years later, following two excellent examples by Robert B. Parker, the author Benjamin Black (who is in reality John Banville) is keeping the tradition of the wise-cracking hard-boiled shamus alive with the latest installment in the Philip Marlowe legacy, The Black-Eyed Blonde.

Raymond Chandler wrote his first novel relating the adventures of Philip Marlowe in 1939. For those that have forgotten, it was titled The Big Sleep and, as one review described it, The Big Sleep is an unavoidable masterpiece of modern literature. Over seventy years later, following two excellent examples by Robert B. Parker, the author Benjamin Black (who is in reality John Banville) is keeping the tradition of the wise-cracking hard-boiled shamus alive with the latest installment in the Philip Marlowe legacy, The Black-Eyed Blonde.

But before discussing Black’s book I need to admit that I regularly listen to rebroadcasts of The Adventures of Philip Marlowe streaming on internet radio. I’ve probably heard them all, including the early Van Heflin episodes, and I now have a real enthusiasm for the voice work of Gerald Mohr whom I long considered one of the greasiest B-movie actors in movies. Radio is my constant companion and with the advent of the internet, my radio is always on and I don’t ever watch television or go to the movies (except streaming on Netflix).

One of the fun things about listening to a lot of old-time radio is getting to associate the voices of certain characters as they pop-up in roles on Johnny Dollar or Sam Spade or Gunsmoke. Three key names to remember are Howard McNear, Parley Baer, and Virginia Gregg, Gregg is the go-to female voice in just about every role requiring a female voice; Howard McNear and Parley Baer show up in the cast list of so many radio dramas that I lost count. For instance, they play Doc and Chester Proudfoot on the radio version of Gunsmoke and, if you follow through into television, both actors were prominent in The Andy Griffith Show, McNear playing Floyd the Barber and Baer playing the Mayor of Mayberry.

One of the fun things about listening to a lot of old-time radio is getting to associate the voices of certain characters as they pop-up in roles on Johnny Dollar or Sam Spade or Gunsmoke. Three key names to remember are Howard McNear, Parley Baer, and Virginia Gregg, Gregg is the go-to female voice in just about every role requiring a female voice; Howard McNear and Parley Baer show up in the cast list of so many radio dramas that I lost count. For instance, they play Doc and Chester Proudfoot on the radio version of Gunsmoke and, if you follow through into television, both actors were prominent in The Andy Griffith Show, McNear playing Floyd the Barber and Baer playing the Mayor of Mayberry.

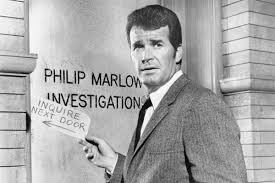

From another angle I was recently asked how seriously the on-screen portrayal of a character such as Philip Marlowe influenced my vision of the fictional character. Perhaps due to the fact that I regularly have read the book before I see the movie, my response indicated that my vision of the character came almost exclusively from the book and more often than not I was highly critical of the movie or television portrayal. I gave as an example the wimpy portrayal of Spenser by the actor Robert Urich on the television series Spenser For Hire. But there are so many other good examples.

Just look at a few of the Philip Marlowe portrayals: Dick Powell, Humphrey Bogart, Robert Montgomery, James Garner, Elliot Gould, Robert Mitchum, Philip Carey, Powers Boothe, Danny Glover, James Caan. If I had to choose, I probably would select Powers Boothe as the closest to my image of Philip Marlowe (although I love the Bogart film).

Just look at a few of the Philip Marlowe portrayals: Dick Powell, Humphrey Bogart, Robert Montgomery, James Garner, Elliot Gould, Robert Mitchum, Philip Carey, Powers Boothe, Danny Glover, James Caan. If I had to choose, I probably would select Powers Boothe as the closest to my image of Philip Marlowe (although I love the Bogart film).

But back to The Black-Eyed Blonde.

Benjamin Black’s (John Banville’s) novel follows in the same sentiment that all the other portrayals of Philip Marlow eventually succumb to: it is a good story, well-written, interesting, and even exciting at times, but Black is no Raymond Chandler and his vision of Philip Marlowe is good but not that good. Listen to Gerald Mohr as Marlowe: it may not be perfect but for radio it is the best out there.

I was born in the 1940s and grew up occasionally visiting Los Angeles, a Los Angeles which still maintained much of the ambiance, good and bad, that Philip Marlowe experienced in Chandler’s fiction. As I read these hard-boiled detective novels many years back I was often reminded of the old Los Angeles that existed into the 1950s. Fond memories of days before the freeways, the Walk of Fame, or the Dodgers. I later went to college in Los Angeles and even then some of the early days of the city remained, even if only in old photographs being sold on Hollywood Boulevard.

I was born in the 1940s and grew up occasionally visiting Los Angeles, a Los Angeles which still maintained much of the ambiance, good and bad, that Philip Marlowe experienced in Chandler’s fiction. As I read these hard-boiled detective novels many years back I was often reminded of the old Los Angeles that existed into the 1950s. Fond memories of days before the freeways, the Walk of Fame, or the Dodgers. I later went to college in Los Angeles and even then some of the early days of the city remained, even if only in old photographs being sold on Hollywood Boulevard.

I think it is this sense of a Los Angeles now long gone which made the Raymond Chandler stories and novels so immediate to me. The Black-Eyed Blonde doesn’t really have it. Despite being a decent story, The Black-Eyed Blonde could have been written with the Los Angeles of the 1980s in mind and maybe even with James Garner as the protagonist. One review actually referred to the novel as “soft-boiled.”

It’s okay—Read it—but not until you’ve read the master, Raymond Chandler.

Share this: