Yup. Moses. [1] Not Jonah. [2] Our lectionary calls for the reading, at the September 3 service, of the story of the call of Moses. The sermon was actually based on a parallel scripture in Matthew, but I was completely taken by the reading from Exodus. I heard it as a large and simple story, almost a plot outline. It sounded preposterous and the more preposterous it sounded, the better I liked it. Today, I’d like to show you the overall arc of that plot outline and a few pictures that came to mind. I am thinking of the pictures as Postcards from the Edge and I am thinking today only of sharing the enjoyment they gave me.

To begin with, let’s imagine that the version of Exodus 3 we now have was composed in Babylon in the 6th Century B. C. for the needs of the Israelite exile community. Maybe some of that is true; maybe all of it. And let’s specify a particular author, so it will be easier to attribute the intentions of an author to him. I’m thinking of a name like Joseph bar Jonah. [3]

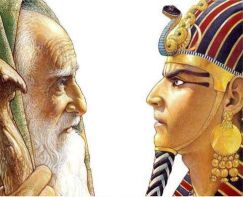

So Joseph writes up the story of the delivery of the Hebrew people from slavery in the land of Israel and since they are slaves [4] in Babylon at the time, there is no reason for him to get all subtle about it.

The Burning Bush

The bush appears to be on fire, but it is not being consumed by the fire. Moses, the  nobleman turned shepherd, had seen a lot of bushes on fire, but never one like this. It struck him as odd and he went to see it on the grounds that it was a natural oddity. I was an anomaly. It was The Anomaly.

nobleman turned shepherd, had seen a lot of bushes on fire, but never one like this. It struck him as odd and he went to see it on the grounds that it was a natural oddity. I was an anomaly. It was The Anomaly.

God waited to see whether Moses would go check out the bush. God didn’t know and had to wait, like Joseph bar Jonah’s readers, to find out. When Moses did turn aside, the first job was to change this encounter from a simple natural anomaly to a profound spiritual interaction. And that needed to happen quickly because Moses was about to get the job offer of his life and the whole thing was completely implausible.

God’s Name

Joseph bar Jonah didn’t need to convince his readers of the power of a name. A name in that society was like the combination to the safe in our society or access to the passwords or authority to write checks on someone else’s account. Knowing a name was a big deal.

Now…Moses didn’t know God’s name. Nor did the Israelites, to whom it would matter, since this God was their ticket out of slavery. [5] Nor did the Pharoah know the name of this god. It wasn’t familiar to him even when he was told what it was and, didn’t see any reason why he should consider it to have authority.

And the name God gives to Moses is completely impenetrable. I have been told by people who know a great deal more Hebrew than I do that the name God gave to Moses can be rendered “I am who I am” or “I will do what I will do.” [6] Those can be used as if they were a name, Yahweh, but knowing that name does not entail having a power over that being.

On the way to using the name Yahweh (or just YHWH), God identifies Himself historically. He says, “I am the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” We don’t know just what that meant to Moses, with his high-grade Egyptian education. Bar Jonah tells us that Moses’s mother and father were Levites. That means that he is in direct descent from Levi, the son of Jacob. So “I am the God of ….Jacob” means I am the God of your family in particular, as well as all the other families.

Now the children of Jacob, i.e. the children of Israel, had been in Egypt for about 400 years by that time [7], so “direct descendant” didn’t mean anything very obvious, even in a tight clan society. And that’s why the same claim didn’t move the elders of the Israelites in Egypt.

So…this is the fish story part…Moses was sent by a God he didn’t know to proclaim imminent release of the Israelites on behalf of a God they didn’t know either and all this was to be accomplished by persuading a polytheistic ruler that he should honor the wishes of a god he had never heard of and had no reason to obey. It is a lose, lose, lose proposition.

God’s Deeds

But as I said, the name God gave to Moses can be understood as “I will do what I will do” and the doing accomplished things that the name could not. Moses was scarcely willing to believe in the project himself, so God gave him three tricks to do. One has to do with a walking stick that turns into a snake and then back; one with a hand that is terribly diseased and then healthy; and one about water that turns into blood when you pour it out. Moses can, apparently, picture being persuasive in Egypt if he has these tricks in his repertoire. They certainly work for the elders of Israel the same way they worked for Moses. They didn’t believe in the name, but they did believe in the deeds.

But as I said, the name God gave to Moses can be understood as “I will do what I will do” and the doing accomplished things that the name could not. Moses was scarcely willing to believe in the project himself, so God gave him three tricks to do. One has to do with a walking stick that turns into a snake and then back; one with a hand that is terribly diseased and then healthy; and one about water that turns into blood when you pour it out. Moses can, apparently, picture being persuasive in Egypt if he has these tricks in his repertoire. They certainly work for the elders of Israel the same way they worked for Moses. They didn’t believe in the name, but they did believe in the deeds.

That must have stung bar Joseph’s readers just a little, because they had the name. But when the army of the foreigners came to haul them away, there were no deeds. Maybe bar Joseph is trying to plant the question, “So…where are the deeds?”

And the Pharoah, as I said, saw no need to honor the extravagant requests of an unheard of deity, but Moses’s tricks were more powerful than those of his own mages. That’s something to think about. And then God brought awful plagues upon the land and the people, just the plagues Moses predicted. So this unheard of God is a god of deeds and He can make you an offer you can’t refuse.

[1] “An extravagant or incredible story,” according to my online Merriam Webster Dictionary, first used in this sense in 1819.

[2] A “great fish” according to the author of Jonah. A “whale” according to the Matthean Jesus, using one of the translations of the Greek, kētos, which could be translated “whale, sea monster, or huge fish.” I am a fan of the translation “sea monster,”myself. It dramatizes all the right things and runs no risk at all of pretending to be scientific.

[3] The parallels with Jesus’s disciple Simon bar Jonah are intentional, though hardly necessary. If you’re going to tell a fish story, you might as well have fun with it.

[4] Not in the same sense as in Egypt, but they couldn’t go home and they couldn’t be the set apart nation, Israel, in Babylon—especially since the site of the Temple was in Jerusalem.

[5] And, according to Genesis 6:3, that is not the name God had used in His dealings with the Israelites, but rather El Shaddai. You see what I mean about this name thing.

[6] And since they are the same verb, they can be mixed and matched. So a scholar could, on good linguistic grounds, propose that God has told Moses that His name was “I am what I will do” or even “I will do what I am.” Either one can be supported by appeals to the history of Israel.

[7] Genesis 15:13. I’m not making a historical argument here, just passing along bar Jonah’s study notes.

Advertisements Share this: