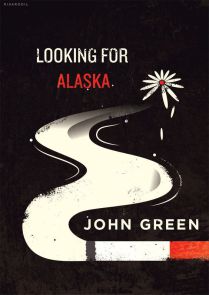

John Green is famous for writing. He writes painfully real characters, with beautiful storylines – and a distinct lack of the generic ‘happy ending’. His debut novel, Looking For Alaska, picked up a stream of awards, and people with (at least one) question: Did Alaska Young – the manic pixie dream girl of Culver Creek – commit suicide, or was her untimely death an accident?

My good friend, Christian, and I read this book at around the same time, and we have conflicting opinions as to how she died. I chose accident, he chose suicide. And since I’m starting this shiny new blog, I decided “where better to post a book-ish argument than a book-ish blog?” So, here goes nothing.

In my opinion, Alaska is Queen of the manic pixie dream girl trope. If you’re reading this and have no clue what that is, a manic pixie dream girl is a cinematic stock-type character who exists to help men and boys in movies and books to pursue their own happiness. The film critic, Nathan Rabin, coined the term when reviewing Kirsten Dunst’s character in Elizabethstown, describing the MPDG character as “that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures”. Now, Elizabethstown was released on October 4th 2005, and Looking For Alaska was published eight months before this, in March 2005.

So, basically, Alaska was busy being a MPDG before MPDGs were officially A Thing.

Turning back to the topic at hand, though, Alaska Young is the beautiful, complicated and mysterious “love interest”, who is full of secrets, cigarette smoke and pink wine. She’s obsessed with the line drawn between life and death, and is fixated with the quote and final words of Simon Bolivar “How will I ever escape this labyrinth?” She makes morbid jokes about death during the course of the book, saying things like “Y’all smoke to enjoy it, I smoke to die” and “I may die young, but at least I’ll die smart”, as well as referencing her unhappiness, saying “What you must understand about me is that I am a deeply unhappy person.”

However, through all her morbid yet quotable lines about death and depression, she doesn’t mention suicide. She wasn’t in a hurry to stop breathing and “pass on” to a different spiritual plane (or whatever you may believe) she was perfectly content with just smoking her cigarettes and drinking her pink wine – and driving at precarious speeds.

But Alaska is a mysterious girl, who functions on a need-to-know basis when it comes to things from her past. It’s only two days before her death, the Pudge finds out about one – if not the most – important event in Alaska’s life: The death of her mother. Clearly she blames herself for this, as she says, “I was a little kid. Little kids can dial 911. They do it all the time. Give me the wine.” This statement can also be used as evidence that she uses drinking to avoid what she’s feeling, since she doesn’t just leave the statement at “They do it all the time”, she asks for the wine almost as though it wasn’t a conscious demand (or at least I think so), naturally drinking away her issues.

She didn’t just drink to drown her feelings, though. She lived her life with reckless abandon, drinking and smoking and pranking to her heart’s content. As Pudge said, after her mother’s death, “She became impulsive, scared by her inaction into perpetual action … but more importantly she’d been scared of being paralyzed by fear again.” It became almost as though she had be reckless, she had to drive fast, drive drunk, have sex with a stream of guys, cheat on boyfriends, and chainsmoke, or she’ll just stop. She’ll stop being. And that must terrify her. That she’ll be just like her mother, cold and simply lying there, doing nothing.

So she made herself impenetrable. She mastered the right half of the Mona-Lisa’s smile, she became a technicolour mystery, with blue painted toenails, and a fiecre sense of loyalty – which is what I’m coming to next.

By now you’ve got to be thinking “But what’s this got to do with how she died?” and my dear reader, it has everything to do with how she died. Understanding the girl – or at least trying to – is what helps the explaination of what happned on the road that night.