★★★½

When two young sisters are abandoned on the doorstep of the Pietà in Venice in 1695, they enter the care of an extraordinary institution: part foundling hospital, part secular convent, and part conservatorio. The girls of the Pietà learn to love God through the medium of music, whether by playing an instrument or by singing in the weekly Masses, which draw admiring crowds to the chapel beyond the grille that prevents any of the performers being seen. And the soloists of the Pietà become stars, their talents as well-known as any opera singer’s, even though they must remain screened away. Of these two abandoned sisters, one, the playful and exuberant Chiaretta, will turn out to have a voice that wins her legions of admirers. The other, Maddalena, looks in vain for an instrument that sparks the inner core of her being. But then she discovers the violin, at around the time that the Pietà hires a young priest to help with giving lessons: a virtuoso violinist and budding composer with flaming red hair, named Antonio Vivaldi.

Last time I read a novel about a composer, I wasn’t exactly scintillated. But of course Vivaldi has the advantage of a much more colourful life than Bach, who toiled virtuously away in Saxony and found a good organ to be the height of excitement. Vivaldi’s world blazes with passion and scandal. Here is Venice at its most scintillating: the Carnival and the canals; the water whose glitter is reflected back in his music; the tempestuous drama of the opera houses. But of course, this world is only hearsay to most of the girls of the Pietà, who come no closer to it than the grille in the visitors’ parlour. Some, however, are talented enough to be invited out to give concerts, which inevitably bring them face to face with all the temptations of the world. And this can be dangerous. For the gentlemen of Venice, there is no being so irresistible as a pure angel of the Pietà.

Corona’s novel focuses on the two different paths that our two sisters take, one of which leads beyond the Pietà walls to a life of constrained luxury; the other remaining within the Pietà for a life of music and teaching. It would’ve been easy to show this as a simple dichotomy between liberation and imprisonment, but Corona is more subtle than that and we see that in many ways the outside world offers a woman (especially a musically-talented woman) fewer chances for self-expression. I remember that I wasn’t entirely convinced by the romance in the last novel I read by Corona (The Mapmaker’s Daughter) and I’m pleased to say that it works better here. Indeed, Corona explores various kinds of attachment between men and woman, of which the physical kind isn’t always the most intense. And none of them are as important as the bond between sisters.

Although I love Vivaldi’s music, I don’t know much about the man and so I read Corona’s note with interest. She evidently did a lot of research before writing her novel, but it comes together well, without feeling forced. She borrowed the name Chiaretta or Chiara (she writes) from a soprano who actually performed at the Pietà, after Vivaldi’s day, while Maddalena is based on a reference to a ‘Maddalena Rossa’ from the Pietà archives. Corona laments that no diaries by the girls of the Pietà have survived; but, if that was the case in 2008 when she wrote the novel, it’s no longer so. New discoveries are being unearthed in archives all the time and, in 2014, Fabio Biondi and his orchestra Europa Galante published a CD (with a bonus DVD) called Il Diario di Chiara, based on the diary of one very such girl. She was a brilliant violinist (coincidentally called Chiaretta), who was abandoned at the age of two months old and taught by Vivaldi at the Pietà. She manifested such talent that she became the foundation’s leading violinist. In this way, fiction sets out a path that actually turns out to be historically very plausible.

Naturally one has to go to listen to Vivaldi after finishing this. I’m tempted to revisit The Four Seasons, which in recent years I’ve regarded as little more than an unimaginative choice for on-hold music. But Corona’s description of the seasonal pastimes evoked by each of the four movements has captured my imagination. I loved her efforts to show how startlingly modern this piece would have sounded at the time, offering occasionally discordant imitations of real sounds or sensations, rather than conforming to ideals about musical elegance. In fact, I should really listen to more of Vivaldi’s violin music full stop. I have many of his operas and oratorios, but his vast repertoire of instrumental concertos remains untapped; not to mention the vast majority of his sacred music. (As I write this, I’ve just bought Fabio Biondi’s recording of La Stravaganza.)

I’m surprised no one has made a film about Vivaldi yet (or maybe they have? Tell me if you’ve heard of one). Part of the reason must be that it’s very hard to find brilliant violinists who can also act (as is shown by The Devil’s Violinist, according to Amazon reviews). But, if one could find a way to have ‘stunt hands’ and just choose an actor, I think the lovely Peter Eggers would make a superb prete rosso. I actually had him in mind all the way through the novel. Vivaldi has been more popular among authors and there’s at least one other novel, which sounds very similar to this one, focusing on his teaching at the Pietà: Vivaldi’s Virgins. That homes in on Anna Maria dal Violin, who also features in this novel as one of the sisters’ friends. I’m keen to read it but obviously not right away, as it doesn’t sound all that different in spirit.

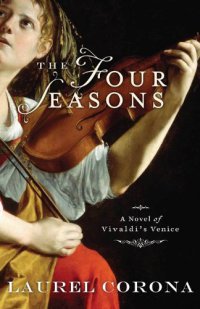

And what’s that lovely Baroque painting on the cover? Uncredited on the book jacket, it’s actually a detail from A Young Woman with a Violin by Orazio Gentileschi (father of Artemisia), which is now in the Detroit Institute of Art.

Buy the book

Share this: