I was sitting at the dining table of a rented holiday cottage in West Bay, idly totting up the senses in which the title of Iain Sinclair’s chapter might be read: ‘After Sebald’ is the title of chapter four of The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City. Grant Gee’s 2012 film Patience is subtitled (parenthetically) After Sebald; and Sinclair follows in Sebald’s footsteps, to an extent, in company with the poet Stephen Watts, a friend of Sebald’s, who sometimes walked with him. Chronologically, Sinclair is, of course, after—later than—Sebald; he is also pursuing him, or an image of him. Much of his writing draws on similar tropes of memory and deep autobiography to those of Sebald: again, this is, in a sense, ‘after’ him. He also touches on the Sebaldian afterlife of conference, festschrift, memorial, tribute: and the influence of Sebald, as man, walker and writer, as presence, as image of ‘writer’, on others, including the writer Rachel Lichtenstein, with whom Sinclair has collaborated in the past. And the afterworld is an abiding concern in Sinclair’s fictional or metafictional world, not least here in the moving elegiac conjuring of Martin Stone. ‘Slow down. Lose yourself among walks laid out with sufficient complexity to confuse the dead. To keep them to allocated spaces. To the chipped ballast of memorial slabs holding them in the ground.’[1]

Post-lunch, convalescing from such mental exertions, I trip over Sinclair’s mention of a book called The Last of England (2004) by Randall Swingler. Now, to a close reader of Ford Madox Ford, that title, The Last of England, sets dogs barking and bell ringers swinging on their ropes.

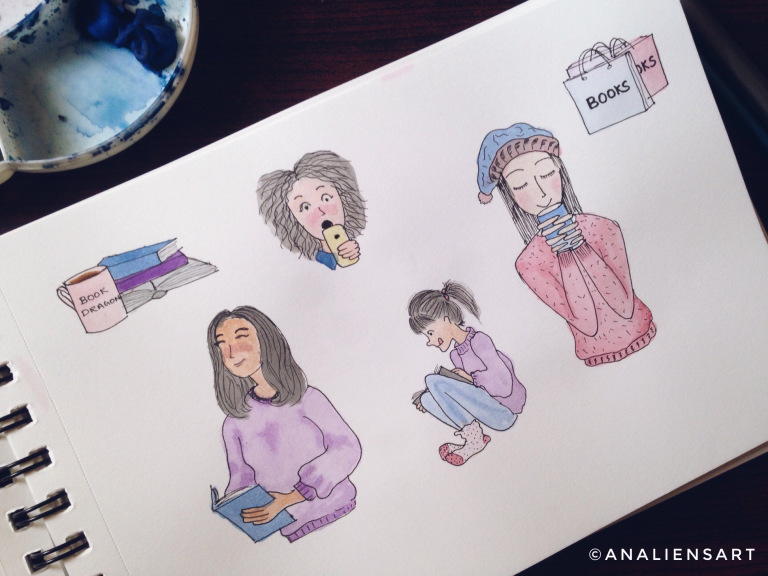

(Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England: Birmingham Museums Trust)

By way of brief explanation, for those immune to such infections, The Last of England is a famous painting by Ford Madox Brown, maternal grandfather of Ford Madox Ford. It exists in two versions—or three, counting the watercolour replica in the Tate—the oil on panel of 1855 (Birmingham Museums Trust) and the 1860 version (oil on canvas: The Fitzwilliam Museum), which seems entirely suitable in the context of any discussion of a writer whose name, nationality and status are far from stable and are strongly marked by doubleness, trebleness—or more. (Sentences like that sometimes appear to be occupational hazards for those with ambitions to write about Ford.)

As well as his several unsurprising references to the picture’s title in his 1896 biography of grandfather Brown, Ford used the phrase in his great postwar tetralogy, Parade’s End, twice in the opening volume and once in the final one. There is a finer symmetry than is at first apparent: the single mention in the closing volume is balanced by the fact that Last Post is itself ‘the last of England’ for Ford in several senses. The whole of the tetralogy had been written abroad but constituted his most searching fictional analysis of this country, while Last Post moved on from recent history to glance at possible futures. Thereafter, the material of his fiction lay elsewhere, in France and the United States. And, arguably, Last Post, his last ‘English’ novel, was the last of his books to be aimed at a primarily British audience.

Ford used the phrase twice more, in It Was the Nightingale, the autobiographical volume most closely related in its themes and treatment to his great novel. Once, because of the restrictions that were being brought in against immigration:

‘What then was to become of England of the glorious traditions? It had been political fugitives and martyrs that had given England her place among the nations. It had been the Flemish weavers, the Anabaptists, the Huguenots, the ceaseless tide of the discontented from every nation that had given England, not alone her tradition of freedom, but her crafts, her system of merchanting, her sense of probity, her very security. . . . This then was the last of England, the last of London. . . . ’

(Cue two minutes’ silence here, looking around us, as we must.)

The second instance concerns Ford’s leaving England for France in November 1922: ‘There was, as I passed through Trafalgar Square, a dense fog and the results of a general election coming in. . . . an immense shouting mob in a muffled and vast obscurity. The roars made the fog sway in vast curtains over the baffled light-standard. That for me was the last of England.’[2]

So, for a moment, familiar with the poet Ted Walker’s memoir and Derek Jarman’s film, plus a couple of other uses of the phrase in book titles, I paused, breathing a little heavily. Had I missed something really significant? I’d heard of Randall Swingler, come across him in a couple of literary histories, in memoirs by several figures, including E. P. Thompson and Julian Symons, which appeared in PN Review—which had also published George Barker’s ‘Elegy’ (‘Randall Swingler, that most honest man’)—and especially in Swingler’s ‘The Right to Free Expression’, published in Polemic, with annotations by George Orwell.[3] As a committed Communist, Swingler was never going to hit it off with Orwell: taking such exception to Orwell’s ‘The Prevention of Literature’ and referring to its author as ‘singularly independent of factual evidence’ made sure of that.

The 2004 publication date Sinclair mentioned made me pause, even within my pausing, though reprints or revised editions of Swingler, who died in 1967, were plausible. Then I suddenly registered the reference to J. H. Prynne, which pointed pretty definitely to Randall Stevenson’s volume in The Oxford English Literary History, Volume 12: 1960-2000: The Last of England?

Not to suggest for a moment that Sinclair’s bracing, exhilarating and often extremely funny book should be defined by a tiny error—but while some errors are merely errors, others exist for just such occasions, to connect with, and stimulate, those ready for such connection. In the past, I’ve commented to others about books particularly poorly proofread who turn out not to have noticed any errors at all; on the other hand, often having read a book I then see a review of it which points in tones of thunder to outrageous shortcomings, blunders and misrepresentations that completely passed me by. Swingler for Stevenson would be puzzling or a speck of grit in the eye for a minority of Sinclair’s readers, I suspect. Even if they noticed, would it really matter to them? Not unless they too had a selection of phrases like ‘the last of England’ wired up to the alarm system of their memory banks.

Besides, that ‘error’ (which already seems to need the qualification of quotation marks) seems quite at home in Sinclair’s chronicle of complex networks of connection and affiliation, all of a piece with a universe of chance encounters, names slightly misheard, images glimpsed through the interstices of blurry weather. ‘We impose connections in a futile attempt to find meaning in a maelstrom of possibilities.’ Elsewhere, he writes: ‘In the state that manifests itself when projects are launched, and when they dictate their terms by way of coincidences and excited discoveries, unexpected phone calls, emails from strangers, I found it difficult to sleep. The streets had become a displacement dream.’ And one more: ‘What I was groping towards was the conviction that different writers, laying down different maps of the same place, enlarge the potentialities of the city. Geography shifts. Individuals dissolve. Place is burnished and dissolved.’[4]

There’s a fascinating video on the London Review of Books website at the moment: Stewart Lee interviewing Iain Sinclair. The fact that Lee several times refers to Sinclair’s book as The Last of London seems to fit as well. . .

https://www.lrb.co.uk/audio-and-video

References

[1] Iain Sinclair, The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City (London: Oneworld, 2017), 58.

[2] Ford Madox Ford, It Was the Nightingale (London: Heinemann, 1934), 86, 137. One of the book’s later editors describes it, in fact, as ‘a companion volume to Parade’s End, reiterating the concerns of the tetralogy with renewed urgency’. See John Coyle, editor, Ford Madox Ford, It Was the Nightingale (1934; Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2007), xiv.

[3] George Orwell, Smothered Under Journalism: 1946, edited by Peter Davison, revised and updated edition (London: Secker and Warburg, 2001), 432-443. Davison’s footnote (443) mentions Swingler’s volumes of poetry and his editorial involvement with several journals in the 1930s and 1940s. Barker’s poem is in PN Review 27, volume 9, number 1 (September-October 1982).

[4] Sinclair, The Last London, 18 (I see I’ve quoted this once before but think it’s earned a repeat), 42, 54.

Share this: