From a piece by John C. Wright, from a few years ago:

In none of the stories I just mentioned, even stories where the image of Our Lord in His suffering nailed to a cross is what drives back vampires, is any mentioned made of the Christ. Is is always an Old Testament sort of God ruling Heaven, or no one at all is in charge.

So why in Heaven’s name is Heaven always so bland, unappealing, or evil in these spooky stories?

I can see the logic of the artistic decisions behind these choices, honestly, I can. If I were writing these series, I would have (had only I been gifted enough to do it) done the same and for the same reason.

It is the same question that George Orwell criticized in his review of THAT HIDEOUS STRENGTH by CS Lewis. In the Manchester Evening News, 16 August 1945, Orwell writes that the evil scientists in the NICE [the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments, who are the Black Hats of the yarn] are actually evil magicians of a modern, materialist bent, in communion with ‘evil spirits.’ Orwell comments:

Mr. Lewis appears to believe in the existence of such spirits, and of benevolent ones as well. He is entitled to his beliefs, but they weaken his story, not only because they offend the average reader’s sense of probability but because in effect they decide the issue in advance. [emphasis mine] When one is told that God and the Devil are in conflict one always knows which side is going to win. The whole drama of the struggle against evil lies in the fact that one does not have supernatural aid.

I myself happen to think Mr. Orwell’s criticism is utter rubbish.

Is Milton’s PARADISE LOST lacking in drama because one know which side is going to win? What about the story of the Passion of the Christ in any of its versions, including the child’s fairytale version as told in THE LION, THE WITCH, AND THE WARDROBE? Or what about any and every version of Dracula? While there may be modern versions where vampires are driven away by leather-clad vampiresses in shiny coats shooting explosive bullets while doing wire-fu backflips, in the older versions of the tale, it was the crucifix that drove off the evil spirits. Merely having God Almighty on your side does not remove the element of doubt nor the element of drama.

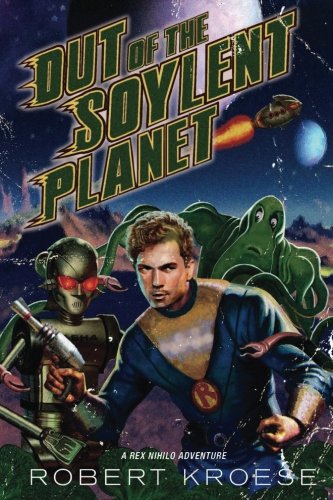

This is something that I’ve had to deal with with the Jed Horn series. Steve Tompkins said in his introduction to Kull: Exile of Atlantis, “a writer who avails himself of the name ‘Atlantis’ gives away his ending.” Similarly, the ending is already established by the mere presence of the Crucifix. THE sacrifice has been made, the war is already won. How can you tell a scary story with that backdrop?

The war is won, but battles may still be lost. And that is where the tension in the Jed Horn series ultimately lies, not only in the fear of being physically squished, tormented, or eaten by the monsters, but by the possibility that the characters might just fall, that this battle might be lost, regardless of the ultimate victory having already been won. The Battle of New Orleans was fought after the War of 1812 was officially over. Our own battles with the darkness are no different.

I tried to establish this in A Silver Cross and a Winchester, way back in 2013. The demons won’t succeed in bringing about the actual end of the world until God says otherwise. But they can still cause a great deal of harm in the meantime, which is why they must be opposed.

Go read the rest of John’s essay; as usual, he is rather more eloquent than I.

Jed Horn #4, Older and Fouler Things, is three weeks away. Go pre-order it.

Advertisements Share this: