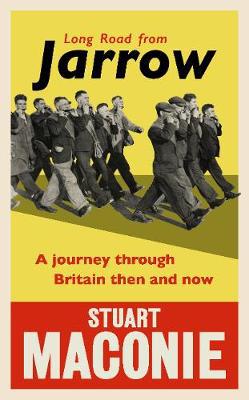

We seem to be living in an era of anniversaries. As well as the whole period from 2014 to 2018 being a commemoration of the Great War (with honour given to major individual battles like Verdun, the Somme and Passchendaele) 2017 has also seen the Centenary of the Russian Revolution, the Balfour Declaration and the birth of Arthur C. Clarke, the 50th anniversary of the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the film The Graduate and the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Closer to home it is the 150th birthday of the beautiful building my workplace is housed in (an excuse for a party of some sort? I do hope so…) I’m not sure I remember quite so many major anniversaries in my childhood and youth (the only ones that stand out are the Queen’s various Jubilees – mostly because of time off school/my own wedding….) but perhaps I just didn’t care enough to remember them. One event which has recently (October 2016) marked what I tend to refer to as a ‘tombola’ anniversary – one ending in a 5 or a 0 – is the Jarrow March. You know, the Jarrow March? The march from Jarrow to, um, London? Because of jobs? Or something? The one which so many people have forgotten about, never heard of or have dismissed as some kind of bolshie nonsense? Well, that’s the one which Stuart Maconie has made the subject of his latest piece of travel writing.

Maconie’s travel writing is always worth a read. He is a keen observer of the places he visits and is never afraid to give you his own views. In this book he decides to follow in the footsteps of the Jarrow Marchers, to find out why they marched, how they were received and whether they are remembered: also, he fancies a nice long walk. Along the way he compares 1936 – with its rise in right-wing politics, wide-spread unemployment and reliance on food handouts and other benefits, and frequent protest marches – with the present day. Some of the comparisons are quite chilling, if I’m honest – at some points the only improvement we seem to have is the NHS – but he is also happy to point out that his nightly accommodation, at least, was a great improvement on the drill halls, schools and churches the marchers were offered. He never downplays the physical effort the march represented but, in order to keep appointments with certain people he meets via social media, he does occasionally jump on a bus. These meetings are often with people who are able to fill in background information on the marchers but he also takes in choral music, a classical piano recital, a pub covers band and a wake. He speaks fondly of many of the marchers themselves (and their dog) and of the Jarrow MP, Ellen Wilkinson, but is scathing of most of the Labour party of the time (who made every effort to distance themselves from the marchers). He’s not fond of Corbyn either but does end his march by meeting Tracy Brabin, the MP for Batley & Spen (elected after the murder of Jo Cox) in the House of Commons.

Maconie’s travel writing is always worth a read. He is a keen observer of the places he visits and is never afraid to give you his own views. In this book he decides to follow in the footsteps of the Jarrow Marchers, to find out why they marched, how they were received and whether they are remembered: also, he fancies a nice long walk. Along the way he compares 1936 – with its rise in right-wing politics, wide-spread unemployment and reliance on food handouts and other benefits, and frequent protest marches – with the present day. Some of the comparisons are quite chilling, if I’m honest – at some points the only improvement we seem to have is the NHS – but he is also happy to point out that his nightly accommodation, at least, was a great improvement on the drill halls, schools and churches the marchers were offered. He never downplays the physical effort the march represented but, in order to keep appointments with certain people he meets via social media, he does occasionally jump on a bus. These meetings are often with people who are able to fill in background information on the marchers but he also takes in choral music, a classical piano recital, a pub covers band and a wake. He speaks fondly of many of the marchers themselves (and their dog) and of the Jarrow MP, Ellen Wilkinson, but is scathing of most of the Labour party of the time (who made every effort to distance themselves from the marchers). He’s not fond of Corbyn either but does end his march by meeting Tracy Brabin, the MP for Batley & Spen (elected after the murder of Jo Cox) in the House of Commons.

This book is a fascinating history of the Jarrow March of 1936 but also of the country as it was at the end of last year. In many ways it feels as if very little has changed but maybe books like this can help us – through gentle humour and a little anger – to make sure that the history of the late 1930s is not allowed to repeat itself.

Jane

Advertisements Share this: