The last year or so has seen an explosion of novels about Agatha Christie, especially fictionalised versions of her 1926 disappearance. Perhaps the highest profile new publication is Andrew Wilson’s A Talent for Murder, the first in a promised series, which has the irresistible tagline: ‘You, Mrs Christie, are going to commit a murder. But before that, you are going to disappear.’ Next to Doctor Who (2008), which pinned the disappearance on a giant alien wasp, this sounds tame.

The Transforming Event in a Nutshell

The basic facts are these: Agatha Christie achieved sudden celebrity in 1926 with the publication of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (a book with an unlikely solution). In the same year, her beloved mother died and her husband asked for a divorce. Overwhelmed, she wrote to her brother in law saying she was going to Harrogate for a bit (we tend to forget this fact, because it rather spoils the mystery), and drove to a Harrogate hotel, where she checked in under the name of her husband’s mistress.

With a few exceptions, nobody heard from Christie in the next 11 days. The story captured the public imagination, with high-scale searches – Dorothy L. Sayers was among thousands of volunteers – media campaigns, and theories. Most people thought she was dead. The police asked Arthur Conan Doyle to help them find Christie. He put them in touch with a psychic who asked to look at a glove and said she’d be found near water (in fact, she was, but that was the last time Scotland Yard consulted Sir Arthur. He’s reported to have asked: ‘Were you expecting Sherlock Holmes?’). Edgar Wallace wrote in the Daily Mail that this was a clever publicity stunt: create a murder mystery to sell murder mysteries.

Christie was eventually recognised and retrieved. She wrote a newspaper column two years later, essentially saying that she had amnesia and didn’t want to talk about it. One interesting line: ‘I remember reading about Mrs Christie. I was convinced that she must be dead.’ And subsequently, she never fielded questions about the disappearance, nor did she trust the media, until her death. In later years, her daughter Rosalind flagged up every reference to the disappearance in the media – people still generally believed that Christie did it for attention – and contemplated legal action. After Christie’s death, some fans were disappointed to find no substantial reference to the events of 1926 in her posthumously published autobiography.

Narrating the Disappearance: A History

Novelizing or dramatizing the disappearance is nothing new, although the Christie estate is understandably hostile to people wishing to sensationalize this very private woman’s private life. The funeral meats had barely been baked, and the threat of libel barely expired, when Kathleen Tynan’s Agatha: The Agatha Christie Mystery appeared in 1977,

adapted into a movie the following year.

In fact, Christie herself first novelized the disappearance in 1934, under a pseudonym. Unfinished Portrait, written as Mary Westmacott, is about a young woman whose marriage is breaking down – a very obvious self-portrait – who disappears, contemplating suicide. She is saved by the kindness of a stranger. But where we might expect the novel to end romantically, as one of her early thrillers surely would, the  character, Celia, decides not to run off with the man who saved her: she doesn’t know anything about him. Whereas Christie married an exciting man she barely knew, which ended badly, every heroine she created after 1926 gets into a love triangle, chooses the sensible man, and is applauded

character, Celia, decides not to run off with the man who saved her: she doesn’t know anything about him. Whereas Christie married an exciting man she barely knew, which ended badly, every heroine she created after 1926 gets into a love triangle, chooses the sensible man, and is applauded

The first major direct fictionalized version of the disappearance occurred with Kathleen Tynan’s romance novel, Agatha, as mentioned, in 1977. ‘Was it suicide, murder, abduction – or something infinitely more subtle?’ enquired the blurb. Tynan was clear in calling her story ‘an imaginary solution to an authentic mystery; the text hints that a writer is going to make herself have amnesia in order to work out the plot animating her own life. The novelized Agatha regains herself when she stops running away from her own problems and starts helping another guest in Harrogate – an investigative journalist – with his.

The book was relatively successful and was quickly filmed, with Vanessa Redgrave as Christie and Dustin Hoffman as the journalist. Check out Sarah Street’s chapter on this in The Ageless Agatha Christie; it is a fraught and fascinating story, and Street tells it brilliantly. Producers deliberately changed much of the book. First, to avoid a lawsuit (which happened anyway) from the Christie estate, the character of Rosalind – Christie’s daughter, then still alive – was removed and the whole mystery tone, the ‘use of her  world’ as producer Gavrik Losey put it, was replaced with a more conventional romantic melodrama, to avoid any conflicts surrounding the right to publicity.

world’ as producer Gavrik Losey put it, was replaced with a more conventional romantic melodrama, to avoid any conflicts surrounding the right to publicity.

Second, Hoffman’s role was beefed up and Redgrave’s title role was played down – blame Hollywood egos! The result was a quaintly haunting movie about an American journalist who finds, manipulates, and falls in love with a pale, wispy, neurotic woman who happens tobe called Agatha Christie. Oh, and there is a rather wonderful – not in the way it was supposed to be – scene in which Christie gets her husband’s mistress to electrocute her. What other way would a murder mystery writer stage her own suicide? She is, of course, foiled/saved by Dustin Hoffman.

1926 in the Twenty-First Century

In the twenty-first century, very few people can remember 1926. In the 1970s, a period drama set in the 1920s would have formed a glimpse of a vanished era, and all the rest, but it would be a vanished era in living memory for many. Our strongest connection with everyday life and 1926 today is the fact that it’s the year the Queen was born. And

that fact itself is loaded with nostalgia and old ways of life. (Interestingly, the other big Christie year, 1952, when The Mousetrap started its West End run, is the year the Queen took the throne and rationing started to end in earnest.)

As such, modern versions o the Christie disappearance treat it in one of two ways: as an historical oddity – a chance to revel in nostalgia and mysteries dehumanized in the way we always do dehumanize people in history – or as a problem that can finally be solved with the benefit of knowledge or methodologies unavailable at the time. We talk about Jack the Ripper in these two ways, too.

There have been more biographies of Christie than it’s worth our time to mention. But two books, specifically about the disappearance, are worth mentioning.

Jared Cade’s Agatha Christie and the Eleven Missing Days (2001, revised in 2011) is in the funny position of being completely unacknowledged by Christie’s estate, but the only biography with direct input from her first husband Archie Christie’s family. It was this study that unearthed the letter to the brother-in-law, and the Daily Mail column in which Christie told the world that she suffered from memory loss. Cade is not overly convinced by the amnesia story, but he’s also not sold on the idea that this notoriously shy and already successful woman would resort to a publicity stunt. Approaching the problem with the logical mind of a mystery addict, Cade has a very human solution: Agatha  wanted to hurt Archie in a spectacular way.

wanted to hurt Archie in a spectacular way.

Andrew Norman, a medical doctor, published his book Agatha Christie: The Finished Portrait in 2006. The pun on the title of Christie’s most autobiographical book shows that he is going into the author’s psychology. Norman concludes that Christie entered into a ‘dissociative fugue state’, a kind of sporadic and reversible amnesia wrought by trauma. This is probably correct, and the sympathetic if unsubstantial book is subsequently considered inoffensive and is sold at Greenway.

But the big move has been towards fictionalizing the mystery in a self-conscious way. It’s almost as if the truth isn’t important. It’s the story that matters. The interesting thing is that the writers rarely try to create a Christie-esque mystery out of the disappearance. Perhaps that would be too cheap, or perhaps we don’t need to know any ‘real’ answer.

A 2002 radio broadcast, The Case of the Vanishing Author, slotted strangely into Radio 4’s Sherlock Holmes series and actually featured Clive Merrison as Sherlock Holmes. It was a story about Arthur Conan Doyle and Dorothy L. Sayers teaming up to find the missing novelist. Doyle is helped by his creation, Holmes, who manifests in a fireplace, and there are some wonderful lines:

Sayers (in disguise): Cor blimey, gov’nor!

Doyle: Working class accents are not your forte.

Sayers: Funny, that’s what my publisher said.

The whole drama is loosely spun from the fact mentioned above, that Doyle was consulted by Scotland Yard. That incident also informed an element of Julian Barnes’ acclaimed novel Arthur and George.

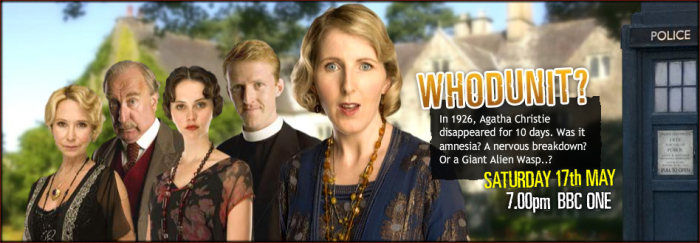

An episode of Doctor Who, of course, brought Christie to the attention of a new generation. Lots of my peers and friends suddenly cared who Agatha Christie was – the rest were won over by Sarah Phelps’ adaptation of And Then There Were None – and I suddenly knew what Doctor Who was. I was in my first year of university when this aired, and it was the first time in my life that I found Agatha Christie conversations not only permitted but actively indulged at the breakfast table.

The episode, ‘The Unicorn and the Wasp’, has some proper British luvvies among the cast and riffs off all the clichés connected to Christie: a country house, a jewel thief on the run, class traitors, vicars with secrets, an amateur sleuth, forbidden love … remember, an author’s recognized hallmarks are rarely connected to them or their work. The titles of over 20 Christie novels are worked into the dialogue – some more successfully than others (‘Murder at the vicar’s rage,’ says the Doctor at one point). It doesn’t matter. The whole thing is a deliberately frothy filler episode in a series that was itself created to fill space.

The time-travelling Doctor visits 1926 and meets Agatha Christie (Fenella Woolgar) who, he knows, is about to go missing for eleven days. He has to find out why, before it happens. And of course, he does, unmasking one country house guest as a giant alien space wasp. Of course. The clue there is Tom Adams’ iconic cover art for Death in the Clouds, which features a wasp, magnified by perspective. I have never found anyone – other than Tom himself, who points out that the wasp in his painting was normal-sized – who disliked this episode. It’s a rare feat to produce something – anything – that no one can take too seriously.

There have been several more earnest TV outings, including Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures, starring Anna Massey and Olivia Williams, which does that oh-so-trendy-at-the-time thing of crafting all the dialogue from Christie’s own words. And there have been a few film proposals, none of which took off. The least said about all these projects, the better.

Recent Novels

Fun fact: Murder, She Wrote was originally pitched as a Miss Marple series, a proposal firmly rejected by the Christie estate. Then it was reworked as a series about Agatha Christie solving murders! Even American TV execs thought this idea was in poor taste – or, more realistically, on a dodgy legal footing – and the idea was vetoed. Many complications ensued before the fabulously naff result captured hearts worldwide. I mention this to show that Agatha Christie was barely in her grave before people started

sniffing around the idea of sending her off to solve murders ifrl (in fictional real life).

She has solved murders in novels, including Dorothy and Agatha (1990) by Gaylord Larsen (I haven’t read it), The London Blitz Murders (2004) by Max Allan Collins (I wish I hadn’t read it), and now in series of books by Alison Joseph (Murder Will Out, 2015; Hidden Sins, 2015) and Andrew Wilson (A Talent for Murder, 2017). Wilson’s series kicks off with the eleven missing days.

But Wilson is not alone. Here are a few novels published in the last few years that revolve, to a greater or lesser extent, around Christie’s disappearance in 1926:

Silence and Circumstance (2015) by Roy Dimond – narrated by Christie’s secretary, Charlotte Fisher. Having forgotten to have any discernible personality, and having suddenly become an American living in some sort of nebulous olden days, Christie gets embroiled in a tangled web of secret organisations and, for no apparent reason, meets every famous person who was alive in some vaguely-defined 1920s. The Woman on the Orient Express (2016) by Lindsay Jayne Ashford – told from three women’s perspectives, including Agatha Christie’s. I didn’t want to like this, but it’s well-researched, emotionally sensitive, and compellingly written. It’s set several years after the events of 1926, and deals with the emotional impact of traumatic incidents. On the Blue Train (2016) by Kristel Thornell – I haven’t got hold of this. A friend of mine says it is ‘too highbrow’. From this review it sounds interesting and a bit po-mo. Have you read it? What did you think? A Talent for Murder (2017) by Andrew Wilson – narrated by Agatha Christie herself. In this story, Agatha Christie is blackmailed and pushed to the edge! Wilson has done more research than anyone else; that is, some people find their clues in the books, some intensely research the events leading up to and surrounding the disappearance, but he has covered every base, even describing Christie’s writing process, beginning with scrawled notes in exercise books. The character is studied, but the story itself is decidedly Wilsonian.

Conclusion

The disappearance, then, has inspired a diverse range of texts. Inevitably, the sense of mystery around it has been manufactured. We want Christie to be mysterious because her books are mysterious. We want her to hide something because everyone in her books is hiding something. If she has to be a quiet, unassuming, and ordinary person, we need to thrust her into circumstances beyond her control – because that’s exactly what she did with her unassuming heroes. But the disappearance is an emotional mystery; it’s an international conspiracy; it’s an otherworldly phenomenon; it’s a comedy of errors; it’s the key to a criminal underworld. It’s no one thing – and, for a writer with the broad appeal of Agatha Christie, this is as it should be.

The disappearance, then, has inspired a diverse range of texts. Inevitably, the sense of mystery around it has been manufactured. We want Christie to be mysterious because her books are mysterious. We want her to hide something because everyone in her books is hiding something. If she has to be a quiet, unassuming, and ordinary person, we need to thrust her into circumstances beyond her control – because that’s exactly what she did with her unassuming heroes. But the disappearance is an emotional mystery; it’s an international conspiracy; it’s an otherworldly phenomenon; it’s a comedy of errors; it’s the key to a criminal underworld. It’s no one thing – and, for a writer with the broad appeal of Agatha Christie, this is as it should be.

The many ways in which the disappearance has been ‘used’ form a strong illustration of Christie’s appeal: through her writing, she has become all things to all people. In these narratives, she is manipulative, pious, fame-seeking, compulsively shy, neurotic, laid back, witty, humourless, quintessentially British, blatantly American, a product of her time, ahead of her time, out of her depth, ready for anything … Like Jesus and the Queen, she is what we want her to be.

I’m not massively keen on the question of ethics, with reference to writing about the disappearance. My views are subjective and not really relevant. I’m also not going to say whether I think Dame Agatha is beaming down or rolling in her grave; put it this way, I doubt she’d have thought much of my research. Among other things, I’m a genre theorist, and the disappearance seems to be a good example of genre flexibility. What interests me here is the unprecedented universality of the Agatha Christie phenomenon.

Find Out More

- Mark Aldridge, Agatha Christie on Screen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

- Michael Apted (dir.), Agatha (Warner Bros, 1979)

- Lindsay Jayne Ashford, The Woman on the Orient Express (Lake Union, 2016)

- Julian Barnes, Arthur and George (Jonathan Cape, 2005)

- Jared Cade, Agatha Christie and the Eleven Missing Days (Peter Owen, 2001)

- Agatha Christie, An Autobiography (Collins, 1979)

- Max Allan Collins, The London Blitz Murders (Berkley, 2004)

- Roy Dimond, Silence and Circumstance (UnTreed Reads, 2015)

- Graeme Harper (dir.), ‘The Unicorn and the Wasp’, Doctor Who, s4e7 (BBC, 2008)

- Alison Joseph, Murder Will Out (Amazon, 2015)

- Gaylord Larsen, Dorothy and Agatha (Onyx, 1990)

- Andrew Norman, Agatha Christie: The Finished Portrait (History Press, 2006)

- Stephen Sheridan (dir.), ‘The Case of the Vanishing Author’, Afternoon Play (BBC, 2002)

- Sarah Street, ‘Agatha (1979): An imaginary solution to an authentic mystery’, in Bernthal, ed., The Ageless Agatha Christie (McFarland, 2016)

- Kristel Thornell, On the Blue Train (Allen and Unwin, 2016)

- Kathleen Tynan, Agatha: The Agatha Christie Mystery (Star, 1977)

- Mary Westmacott, Unfinished Portrait (Heinneman, 1934)

- Andrew Wilson, A Talent for Murder (Simon and Schuster, 2017)

Advertisements Share this: