“Wake me… when you need me.”

For Halo 1, we looked at how the Master Chief was a well-defined character and how the game articulated his fears, flaws, and demonstrated, through his movement and actions, his surprisingly expressive personality.

For Halo 2, a story that is half Shakespearean drama and half 80s action flick (with all the emotion, brilliance, and ridiculousness that that entails), we explored the ways in which the Master Chief’s characterisation was undone – how it was the origin of the whole notion that the Chief is just a “vessel” character.

And now, we come to Halo 3…

REAL MEN DON’T NEED ‘CHARACTERISATION’

Halo 3 is weird…

The situation with Halo 3 is that we’ve got the set-up and clear intention for quite an emotionally-charged story as the trilogy concludes.

Thel is in pursuit of revenge against the Prophet of Truth, while the Master Chief has been separated from Cortana, who is in the clutches of the Gravemind back on the Flood-infested High Charity, and he’s promised to come back for her.

The stakes are cosmic in-scale because the Halos are all primed and ready to fire, but the driving force for how the plot is driven to its conclusion is found in the personal motivations of the two main characters. And that’s fantastic, I completely agree that this is how Halo 3‘s story should have been delivered…

But there’s a problem.

Thel was the protagonist of Halo 2, we followed his emotional journey and overall arc as a character which culminated in forming an alliance with humanity and he’s now seeking revenge against the Prophet of Truth. This wasn’t just a landmark moment for changing the layout of the Human-Covenant war, but it consolidated what I feel are Halo‘s two driving themes: truth and reconciliation.

Trouble is, Thel is relegated to the role of ‘trusty sidekick’ in Halo 3 and there aren’t really any moments in the game that meaningfully build up to the moment where he plunges that sword through Truth’s back. Thel is definitely around in the campaign, you spend a great deal of time with him, but there’s only that one scene at the start of Crow’s Nest where the Prophet of Truth speaks to our heroes directly (the rest are him zealously pontificating to his followers as a hologram) and he doesn’t even address Thel – he specifically calls out the Chief instead.

Likewise, Bungie’s intentions with the Master Chief are really quite unclear in this game because it’s like they were shooting for this awkwardly inconsistent middleground between him being a character and a “vessel”.

Halo 3 does a pretty good job of presenting us with a story where the emotional stakes are the highest they’ve been yet in the trilogy, but it’s offset by how little emotion and substance they actually give the two main characters beyond a couple of instances. It’s all riding on the previous game’s establishment rather than doing anything to meaningfully build on those conflicts. Following on from Halo 2‘s characterisation of the Master Chief, he remains very inanimate throughout the cutscenes – further distancing the character from his portrayal in Halo 1.

Following on from Halo 2‘s characterisation of the Master Chief, he remains very inanimate throughout the cutscenes – further distancing the character from his portrayal in Halo 1.

While Halo 2 had its bombastic action sequences, Halo 3 is comparatively calmer in its cutscene action and primarily serves as a series of interludes for exposition.

The first half of the game takes place on Earth with nothing really going on in terms of the plot (which very suddenly materialises about half way through Floodgate), it’s more about getting from Point A to B while fighting Covenant along the way. And that’s completely fine, that just means you’ve got to use that layout to do more with the characters, setting, and the overall theme of the text.

But they didn’t do that…

I mentioned back in the section of Halo 2 that it was disappointing to see the Master Chief cease all interaction with the Marines, whereas Halo 1 used that as a means to establish some of the more subtle aspects of his characterisation.

The same rings true in Halo 3, as the Chief has absolutely nothing to say to his fellow soldiers.

There’s some intention in that, as the Master Chief is a legend to humanity – one of them, yet separate. But it really feels less interesting to me when he’s actually portrayed as being separate from the people he’s fighting alongside because the Master Chief that I know from the original game and from the books is not separate from them at all.

Rather than being a legend because he’s separate and ‘different’ from everybody else, I prefer the idea of him being a legend because of the word-of-mouth stories that people have of him while distinctly characterising the Chief as being one of them – making those stories about him more personal rather than appealing to the ego of the player by articulating it as: “He walked through a battlefield and killed loads of enemies and saved us and it was awesome! What a guy!”

Indulge me here because I’m now going to spend a bit of time not talking about Halo 3…

In order to articulate my perspective on the Master Chief, I’m going to turn to Eric Nylund’s novel, released in 2003, Halo: First Strike. There’s some absolutely incredible character moments in First Strike for the Master Chief, so let’s begin with one where he considers the difference between himself and a Marine.

The larger ships passed directly overhead and blotted out the sun. In the darkness, the cockpit lights automatically adjusted and flooded the display panels with the purple-blue frequency the Covenant favored.

The Master Chief realised that he, too, had been holding his breath. Maybe he and Locklear were more alike than he had realised.

He took a closer look at the ODST: The wild, desperate look in his eyes and the flaming-comet tattoo covering his left deltoid seemed almost alien to the Master Chief. The man had survived the Covenant and the Flood on Halo, and he had been lucky and resourceful enough to escape in one piece. True, his emotional responses were uncontained… but give him the same augmentations and a set of MJOLNIR armor and what was the difference between the two of them? Experience? Training? Discipline?

Luck?

John had always felt the other men and women in the UNSC were different; he’d felt at ease only with the other Spartans. But weren’t they all fighting and dying for the same reason? [Halo: First Strike, page 174 (Kindle edition)]

That single moment informed not only the rest of the book’s exploration of the Chief’s characterisation, but is thematic set-up that would later be paid off in Halo 4…

That single moment informed not only the rest of the book’s exploration of the Chief’s characterisation, but is thematic set-up that would later be paid off in Halo 4…

In First Strike, the central conflict for the Master Chief isn’t just the physical imperative to destroy the Covenant, but the emotional dilemma presented to him by Catherine Halsey regarding what to do with Avery Johnson.

Back in Halo 1, Johnson was present at the containment facility where Jacob Keyes and the other Marines present first encountered the Flood. Johnson, of course, survived and escaped Installation 04, handwaving the question of “How the hell did you made it back home in one piece?” with “It’s classified”. Sorry folks, you gotta read the book!

In First Strike, the idea is postulated that Johnson actually has some form of immunity to the Flood (an idea that has since been retconned). Halsey decides to teach the Master Chief one more lesson and places a choice in his hands in the form of two data chips containing reports of what happened at Installation 04, one of which has to be sent to ONI.

One contains the full truth, including Johnson’s supposed immunity so humanity has a one-in-a-billion chance to create a cure, but will kill Johnson so ONI can dissect him; the other redacts that information.

John’s decision here is what informs a huge shift in perspective for Halsey and the value placed on an individual’s life.

Where she had previously been able to reconcile the notion of sacrificing others for the greater good, this eventually takes an immense toll on her and she looks to the Master Chief to vindicate this philosophical change.

Her eyes focused past him as she struggled to find the words to match her conflicting emotions. “For a long time I had thought that we had to sacrifice a few for the good of the entire human race.” She took a deep breath and let it go with a heavy sigh. “I have killed and maimed and caused a great deal of suffering to many people – all in the name of self-preservation.” Her steely blue gaze found him. “But now I’m not sure that philosophy has worked out too well. I should have been trying to save every single human life – no matter what it cost.”

Dr. Halsey pushed the tray bearing the data crystals toward the Master Chief. “If you give ONI the first report, they may be able to find a countermeasure for the Flood. Maybe. They would have a slightly better chance, however, if you give them the second report.”

“Then I’ll give them the second report.” He picked up the crystal.

“Which will murder Sergeant Johnson,” she said with a chill in her voice. “ONI will not be satisfied to take a sample of blood. They will dissect him to find out how he resisted the Flood. It will be a billion-to-one shot that they’ll ever replicate his unique medical conditions – but they’ll do it anyway. They will kill him because the trade-off is worth it to them.”

The Master Chief picked up the other crystal and then stared at them both lying in his gauntleted hand.

“Is it worth it to you, John?” she asked. He curled his hand in a fist and held it close to his chest.

“Why do you want me to make this choice?”

“One last lesson. I’m trying to teach you something it’s taken me all my life to realise.” She cleared her throat of the lump thickening there. “I’m giving you the chance to make the decision that I thought I couldn’t make.” [Halo: First Strike, page 245-6]

There’s some debate to be had over the validity of Johnson being immune to the Flood, it was certainly one of the “less appealing” ideas that Bungie decided to retcon. But it’s something that is used in a dilemma that brilliantly illustrates something about the Master Chief’s character that was seeded in Halo 1, going back to that moment where he places that reassuring hand on the Marine’s shoulder.

There’s some debate to be had over the validity of Johnson being immune to the Flood, it was certainly one of the “less appealing” ideas that Bungie decided to retcon. But it’s something that is used in a dilemma that brilliantly illustrates something about the Master Chief’s character that was seeded in Halo 1, going back to that moment where he places that reassuring hand on the Marine’s shoulder.

The value he places on an individual life.

A life spent versus a life wasted.

Halsey has been quite knowingly chipping away pieces of her own humanity because of the awful decisions and sacrifices she’s had to make in the name of humanity’s survival. One of those awful decisions was the Spartan-II project, which culminated in John standing before her and facing the same question she’s been wrestling with for decades.

What is the value in preserving the human race if we sacrifice our own humanity in the process?

What’s easy to forget is the fact that the Chief initially decides to give the chip that will kill Johnson, believing that his duty is to humanity and the life of one person is indeed worth that – that the one-in-a-billion chance of recreating Johnson’s biological fluke was worth it. He gives the chip condemning Johnson to Elias Haverson (another survivor of Installation 04), who later dies with Admiral Whitcomb – but not before he passes the chip to Johnson to give to ONI before his death.

And then Johnson comes up with the plan that is what ultimately saves Earth in Halo 2, the plan that destroys the Unyielding Hierophant and four hundred and eighty eight Covenant ships – a full invasion force that would have steamrolled Earth and consolidated humanity’s extinction.

The Prophet of Regret was left with only twelve ships to attack Earth instead of five hundred.

Just as Halsey once said to Jacob Keyes that a six year old boy could make all the difference in the universe…

“What difference could a child make?”

One of her eyebrows arched. “This child could be more useful to the UNSC than a fleet of destroyers, a thousand Junior Grade Lieutenants – or even me. In the end, the child may be the only thing that makes any difference.” [Halo: The Fall of Reach, page 19-20 (Kindle edition)]

… the Chief realises that one person, one choice, made in the right moment, can change everything.

Johnson passes the chip to the Chief at the end of the book (not knowing its contents), and the Chief concludes that he was wrong. He was too focused on the big picture, as Halsey had been, so he decides to send ONI the chip that omits the information about Johnson’s alleged immunity.

To paraphrase a truly wonderful speech made in a recent episode of Doctor Who: humanity is measured by the value you place on a life. An unimportant life. A life without privilege – that privilege being, in this period of the Halo universe’s history, survival. Whether it’s a six year old boy playing king of the hill, or a Marine sergeant who just happens to possibly have survived the Flood because of some biological mishap – their value is the same.

That’s what defines an age. That’s what defines a species.

That’s what defines humanity.

It’s why the Chief is so moved by the deaths of the survivors of Installation 04, which is something that he equates to the loss of his fellow Spartans:

Grace, Will, and Fred were alive, but Li, Anton, and Warrant Officer Polaski had been killed in action. He remembered Polaski’s scream, then Anton’s outline as the flash of white-hot fire swept over the hull.

“Acknowledged,” he said as graciously as he could muster, but he heard bitterness give an edge to his voice.

It struck him as odd that Polaski’s death affected him as well. He’d seen thousands of UNSC soldiers die. She hadn’t hesitated to transport Blue Team on a mission that was insanely dangerous. She had survived the battle of Reach, the crash landing on Halo, the Flood, and everything else – then she had bravely volunteered for this mission, too, and perhaps saved all their lives.

She might have made a good Spartan. There were worse eulogies. [Halo: First Strike, page 235 (Kindle edition)]

This isn’t even the first eulogy that the Master Chief gives in the books. In The Flood, which I talked about extensively with regards to Halo 1, the Master Chief discovers the body of a Marine when 343 Guilty Spark transports him to the Library – Staff Sergeant Marvin Mobuto. It turns out that the Chief was not the first Reclaimer that Guilty Spark turned to in order to get the Index to activate the ring and he takes a moment to honour the man’s death.

This isn’t even the first eulogy that the Master Chief gives in the books. In The Flood, which I talked about extensively with regards to Halo 1, the Master Chief discovers the body of a Marine when 343 Guilty Spark transports him to the Library – Staff Sergeant Marvin Mobuto. It turns out that the Chief was not the first Reclaimer that Guilty Spark turned to in order to get the Index to activate the ring and he takes a moment to honour the man’s death.

As he proceeded deeper into the Library, he found a corpse – a human one. He stooped to examine the body.

It wasn’t pretty. The Marine’s body was so mangled that even the Flood couldn’t make use of him. He lay at the center of a large bloodstain wreathed by spent brass.

“Ah,” 343 Guilty Spark said, peering down over the Spartan’s shoulder. “The other Reclaimer. His combat skin proved even less suitable than yours.”

The soldier looked up over his shoulder. “What do you mean?”

“Is this a test, Reclaimer?” the Monitor seemed genuinely puzzled. “I found him wandering through a structure on the other side of the ring, and brought him to the same point where you started.”

The Chief looked down at the body and marveled at the fact that anyone could make it that far. Even with his physical augmentation, and the advantages of his armour, the Spartan was reaching the end of his endurance.

He checked, found the leatherneck’s dog tags, and read the name. MOBUTO, MARVIN, STAFF SERGEANT, followed by a service number.

The Chief put the tags away. “I didn’t know you, Sarge, but I sure as hell wish I had. You must have been one hard-core son of a bitch.”

It wasn’t much as eulogies go, but he hoped that, had Sergeant Marvin Mobuto been there to hear it, he would have approved. [Halo: The Flood, page 243-44 (Kindle edition]

Now, as I’ve mentioned, some of the Chief’s characterisation in terms of his dialogue is a bit off in The Flood, and his line here is one example of that. But the act of stopping to eulogise a fallen soldier is something that he does in multiple books, so, on a conceptual level, this is a distinct part of his character.

This seems like a bit of a tangent, but I wanted to talk about it because the care that the Master Chief has for the lives of his fellow soldiers is perhaps the single most prevalent aspect of his characterisation throughout the books.

I’ve deliberately chosen some of the more obscure examples here from The Flood and First Strike because The Fall of Reach has some of the more obvious and talked about instances.

But when we think of the Master Chief in the original trilogy, he doesn’t really have an arc – he finishes the fight pretty much as the same person he was when he began it in Bungie’s articulation of the character, which, again, runs contrary to how they big up the emotional stakes for a character who is presented as being only minimally invested in them. But the novels present such a rich and emotional maturation of his perspective that was only ever kind of reflected in Halo 1.

It’s why the ‘othering’ of the Master Chief from his fellow Marines in Halo 2 and 3 bugs me so much, and why I love some of the very interesting ways that Halo 4 picks up on and critiques that approach to his character. On a purely functional level, the breaking of immersion comes into this as well. There are several moments where Marines talk to the Master Chief and ask him things… only to be met with silence. He has a grand total of seven lines between Arrival and The Storm (thirty four in the whole game – hey, seven references at the expense of characterisation!). A particular example that comes to mind for this is after the first ‘Cortana moment’ in the opening mission where one of the Marines asks if Chief is alright, another noting that “your vitals just pinged KIA!”

On a purely functional level, the breaking of immersion comes into this as well. There are several moments where Marines talk to the Master Chief and ask him things… only to be met with silence. He has a grand total of seven lines between Arrival and The Storm (thirty four in the whole game – hey, seven references at the expense of characterisation!). A particular example that comes to mind for this is after the first ‘Cortana moment’ in the opening mission where one of the Marines asks if Chief is alright, another noting that “your vitals just pinged KIA!”

And that’s never addressed again. We just move on like nothing happened…

When the Chief sees a vision of Cortana leading him to the controls that reveal the rebuilt Installation 04, Thel asks what he sees… Chief says nothing and Thel never questions it or brings it up again.

Eight years later, Halo 5 would repeat this exact same problem with the way in which Blue Team (don’t) react to the Chief’s Domain-induced vision.

In both instances, in Halo 3 and 5, it’s really weak writing. The Cortana and Gravemind moments were really poorly implemented into Halo 3 from a gameplay perspective, but, far from being redeemable as something that enriches the story, their use in that capacity is just as narratively arid.

This is a major sub-plot that we’re supposed to be emotionally invested in, but the character we’re experiencing this through never reacts to these flashes of seeing his friend in pain. Never shows any investment, except for one or two moments when he has to. It’s because he’s a “vessel” for the player, right? So we’re supposed to project our care onto the Chief… but that’s really quite a big ask of the player when you don’t allow for the circumstances of that care to form in the mind of the player, since their relationship is portrayed in Halo 2 as pretty one-sided, owing to the Chief’s lack of dialogue.

You’re supposed to care because she’s around, makes snarky comments that inform a trademark aspect of the franchise’s humour, and then you have to leave here behind, I guess?

It’s paradoxical. And, again, quite contrary to Halo 1‘s articulation of their relationship. We’re further supposed to care about the Master Chief’s relationship with Johnson, Miranda, and Thel, but, as was the case with Halo 2, we barely get anything that portrays these things as being anything but one-sided. The level of depth to their understanding of one another in First Strike is leaps and bounds beyond anything presented in the games.

We’re further supposed to care about the Master Chief’s relationship with Johnson, Miranda, and Thel, but, as was the case with Halo 2, we barely get anything that portrays these things as being anything but one-sided. The level of depth to their understanding of one another in First Strike is leaps and bounds beyond anything presented in the games.

It’s the lack of a reaction to these huge, larger-than-life things that bothers me as a pervasive characterisation issue.

The Flood show up at Earth and Thel ludiocrously asks: “What is it, more Brutes?”

As if he doesn’t know what the billowing trail of Flood spores coming out of a Covenant ship looks like…

The Chief just says: “Worse.”

That’s the extent of his reaction to the Flood arriving on Earth. It’s one word line that comes across as rather pointless since it gauges no emotional response and it comes from having to contrive a comically nonsensical line from Thel.

Later, the Flood shows up at the Ark with High Charity and at absolutely no point does anybody wonder what has happened to Earth, since, last they heard from Cortana’s message, which Rtas puts in no uncertain terms… the Flood were heading to Earth in full force.

Rtas: “Did you not hear? Your world is doomed. A Flood army, a Gravemind, has you in its sights. You barely survived a small contamination…”

Lord Hood: “And you, Shipmaster, just glassed half a continent! Maybe the Flood isn’t all I should be worried about…”

Rtas: “One single Flood spore can destroy a species. Were it not for the Arbiter’s counsel, I would have glassed your entire planet.”

Halo 3 gets overly swept up in its action, in upping the stakes, and never really slows down to think about asking any questions that come up along the way. The game’s overall pacing mostly doesn’t enable moments like that, but even when it does we rarely see anything come of them. It really hurts the storytelling because I feel that any half-decent story really should have more of a tangible sense of awareness of what is at stake from the main character. They should care. I can’t project my own care onto the Chief because nothing is there to make me feel like I should…

To have the Master Chief falter for a brief moment and wonder what has happened to Earth, to then be reassured by Thel, would be such a small-yet-significant thing to do in service of both of their characters.

Thel was the one who burned Reach (and that was just one of several worlds he’s responsible for glassing) – taking something away from the Chief.

The Chief destroyed Installation 04, resulting in Thel’s disgrace and torture – something that took everything away from him at the time.

Now the two of them have risen above that and they’re on the same side, fighting for the same thing, by virtue of truth and reconciliation. To have that friendship shown to us through an act as simple as a reassuring hand on his shoulder, working as a parallel to Halo 1, would have done a lot to consolidate the more emotional story that Bungie were trying to tell. And it would have been told through an action, not through dialogue that could be deemed extraneous.

Instead, the overall arc of Halo 3‘s conflict feels akin to Frodo going to Mordor and tossing the ring into the fire without a second of hesitation, going through the entire The Lord of the Rings trilogy without a single moment where Frodo’s confidence and integrity is compromised.

The third act of a trilogy is what I’m always the most wary of because too many fall into the trap of being overly formulaic, desperate to deliver an explosive climax and reach the finish line without doing a whole lot in the build-up to that. Third acts tend to be a lot more focused on the plot because they’re stories that are about resolution, but in following this they often tend to neglect other areas of storytelling.

Halo 3 occupies a weird, ‘other’ space. The first half of the game doesn’t really deal with the core plot (when it really should, in some respect, by having the Covenant kidnap humans for Truth to use to activate the Ark), but fails to instead focus on the characters and even articulate reasons to care about the setting. The last four missions then try to throw everything into one and the result is a bit of a mess, saved, in a broad sense, by the fact that Bungie is really good when it comes to presentation. Back in my post on Halo 1, I said that there were two things that I wanted to talk about regarding stuff from the books that did a lot to ground and humanise the Master Chief’s characterisation. I talked about the scene in The Flood where the Chief gets to sleep, eats a hot meal, and has a shower, but there’s another major bit of character-building that is present in both The Flood and First Strike (Nylund’s second novel)…

Back in my post on Halo 1, I said that there were two things that I wanted to talk about regarding stuff from the books that did a lot to ground and humanise the Master Chief’s characterisation. I talked about the scene in The Flood where the Chief gets to sleep, eats a hot meal, and has a shower, but there’s another major bit of character-building that is present in both The Flood and First Strike (Nylund’s second novel)…

The Master Chief’s intense fear of the Flood.

Lemme quote some passages at you:

It was as if something had rewritten the Elite, reshaped it from the inside out. The Spartan felt an unaccustomed emotion: a trill of fear. An image of helplessness – of screaming at a looming threat, powerless – flashed through his mind, a snapshot of his cryo-addled dreams aboard the Pillar of Autumn.

No way is that going to happen to me, he thought. No way. [Halo: The Flood, page 223 (Kindle edition)]

The entire battle consumed no more than two minutes but it left the Chief shaken. Could Cortana detect the slight tremor in his hands as he reloaded both weapons? Hell, she had unrestricted access to all of his vital signs, so she knew more about what was going on with his body than he did. [Halo: The Flood, page 277 (Kindle edition)]

Without warning, a combat form leaped on his back and smashed a large wrench into his helmet. His shield dropped away from the force of the blow, which allowed an infection form to land on his visor.

Even as he staggered under the impact, and pawed at the form’s slick body, a penetrator punched its way through his neck seal, located his bare skin, and sliced it open.

The Spartan gave a cry of pain, felt the tentacle slide down toward his spine, and knew it was over.

Though unable to pick up a weapon and kill the infection form directly, Cortana had other resources, and rushed to use them. Careful not to drain too much power, the AI diverted some energy away from the MJOLNIR armor, and made use of it to create an electrical discharge. The infection form started to vibrate as the electricity coursed through it. The Chief jerked as the Flood form’s penetrator delivered a shock to his nervous system, and the pod popped, misting the Spartan’s visor with green blood spray.

The Chief could see well enough to fight, however, and did so, killing the wrench-wielding combat form with a burst of bullets.

“Sorry about that,” Cortana said, as the Spartan cleared the area around him, “but I couldn’t think of anything else to do.”

“You did fine,” he replied, pausing to reload. “That was close.” [Halo: The Flood, page 323 (Kindle edition)]

The Engine Room hatch opened, an infection form went for the Master Chief’s face, and he fired a quarter of a clip into it. A lot more bullets than the target required, but the memory of how the penetrator had slipped in under the surface of his skin was still fresh in his mind, and he wasn’t about to allow any of the pods near his face again, especially with a hole in his neck seal. [Halo: The Flood, page 327 (Kindle edition)]

And the Flood. He stared out from the front viewport and fought down his revulsion at the memory of the Flood outbreak. Whoever had constructed Halo had used it to contain the sentient, virulent xenoform that had nearly claimed them all. The rapidly healing wound in his neck, inflicted by a Flood Infection Form during the final battle on Halo’s surface, still throbbed.

He wanted to forget it all… especially the Flood. Everything inside him ached.

[…] The Master Chief’s hand curled into a fist, and for a moment he felt the urge to slam it into something. He relaxed, surprised at his frayed temper. He’d been exhausted in the past – and without a doubt the fight on Halo had been the most harrowing of his career – but he’d never been prone to such outbursts. The struggle against the Flood must have gotten to him, more than he’d realised. [Halo: First Strike, page 34 (Kindle edition)]

Character writing is often at its best when our heroes and villains are vulnerable. I’ve even talked about this with regards to the Gravemind and certain things that Bungie cut from Halo 3 that really enhance his characterisation. The books give us these glimpses into the emotional weight pressing down upon our heroes, which, further, beautifully enriches the physical conflict.

Character writing is often at its best when our heroes and villains are vulnerable. I’ve even talked about this with regards to the Gravemind and certain things that Bungie cut from Halo 3 that really enhance his characterisation. The books give us these glimpses into the emotional weight pressing down upon our heroes, which, further, beautifully enriches the physical conflict.

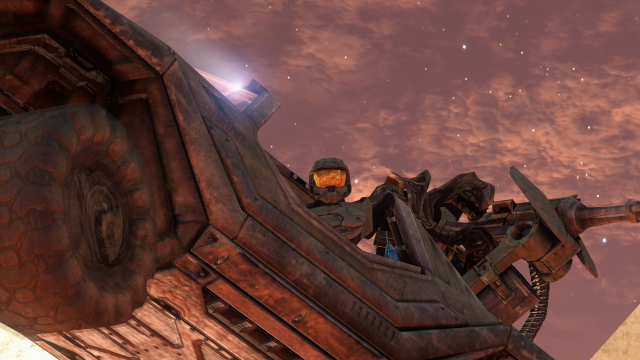

In Halo 3, when the Master Chief decides to single-handedly brave the Flood-infested High Charity in order to find and rescue Cortana… he just looks down at his boot, which gets a bit of Flood goop on it and he quite nonchalantly shakes it off. It’s devoid of any feeling and the cinematic direction of the scene really doesn’t do anything to create a sense of tension or claustrophobia – it’s all wide shots and flat angles, which makes the Flood seem like an incidental part of the scenery rather than this ravenous, relentless parasite that has cannibalised an entire space station.

I lengthily spoke about how Halo 1 managed to do a pretty decent job of conveying John’s fear because of the storytelling done through the stylised cinematography – they actually did a substantial amount of character work in a scene where the Master Chief is just standing outside a locked door and it made the Flood scary without even being there.

Not so, in Halo 3… Instead, you just get about a dozen Cortana and Gravemind moments thrown at you.

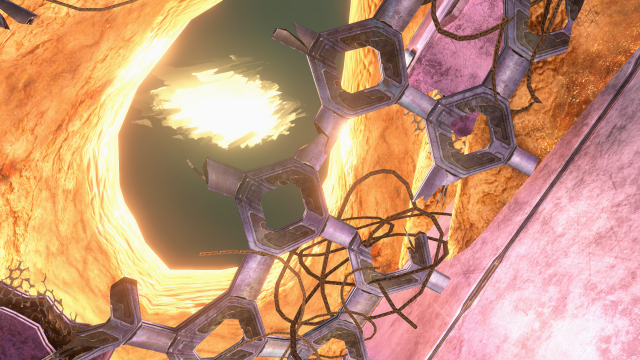

High Charity is just this singular shade of a very bright brown, with a few purple bits here and there, where the previous Covenant architecture is present. I love the artistic design principle of what they were going for with the Flood in Halo 3, the ‘endoscopic voyages’ feeling is really fitting, but it looks a whole lot better in the concept art than in the game. In all fairness, there’s context to take into account here because the Cortana mission ended up being cobbled together by chopping off what was originally supposed to be the second half of Floodgate, as it originally consisted of the level layout and geometry that made the Cortana mission – but that affected the level design, whereas the problems with the Flood in Halo 3 extend across the writing, visuals, and overall presentation.

The Chief isn’t even effective as a “vessel” for the player here because the Flood retain so little of their fear factor in this game, the directing style for the cinematics does nothing to pick up the slack for the lack of actual characterisation, and he’s a poor cipher for this part of the setting because High Charity holds no real meaning to him.

What makes this worse is that we have a definitive statement from Vic DeLeon (digital artist for Bungie and 343 Industries, and is now at Highwire Games) as to “what could have been” in his extensive PowerPoint back in 2011 – Halo 3: Flood Alien Level Autopsy.

In slide 29, we see that there were plans for us to fight through the Mausoleum of the Arbiter once more, facing a Flood-infected Arbiter army just before we get to Cortana.

One hundred and eighty two Flood-infected Arbiter corpses…

That would have been such a brilliant contrast to the previous fight we had in the Mausoleum in Halo 2, where it’s this adrenaline-pumping, badass, all-out conflict between the different species of the Covenant. In terms of tone, this fight would be just plain horror.

Imagine Thel being with you at that point, having just killed the Prophet of Truth in the previous mission, and what that would mean for him – to be killing the revived forms of Sangheili warriors the Prophets had turned into their puppets. How he could have been one of them if he’d died like he was supposed to in Halo 2. How each cut from his energy sword is like severing the link to another corrupt piece of history.

The Master Chief and Thel are in the Mausoleum, the dead Arbiters awaken, and Thel tells him to keep going. Against the Chief’s protest, Thel says that this is his fight. Chief obliges and carries to trying to reach Cortana, the door shutting behind him, locking Thel in.

As you’re heading back to escape after rescuing Cortana, you’d go back to the Mausoleum and Thel is there, still alive. The Arbiters all dead.

(Yeah, you better believe my shameless rip-off of Serenity’s ‘River vs the Reavers’ scene!) Now, I’ve criticised Halo 3 for getting too swept up in its action and finding no room for the smaller moments… but there are a couple of notable exceptions.

Now, I’ve criticised Halo 3 for getting too swept up in its action and finding no room for the smaller moments… but there are a couple of notable exceptions.

The Chief seems to oddly become more interesting and reacts more whenever Guilty Spark is around. From the scene at the end of Floodgate where he confronts the Monitor for trying to kill him and Cortana on Installation 04, to the surprise, snark, and even care he demonstrates at the Ark’s Cartographer. I really like these moments, but there’s so few of them throughout the game it just doesn’t leave a lot to dig into and analyse.

The reunion between the Chief and Cortana, despite the immense problems of how she was written in Halo 3, feels like a moment where time… stands still. Just for a moment. A promise is fulfilled…

Likewise, Johnson’s death is something that has never really hit me, but it handles the Chief’s reaction beautifully – the way he stands up, the camera looking at him from the back as he sighs and takes a moment to regain his composure. And a new promise is made…

“Don’t let her go. Don’t ever let her go.”

Of course, it would be remiss of me not to point out the fact that we spent the entirety of the game building up to rescuing her, the plot bending over backwards to bring us up to this point… and then, one mission later, she’s left to rot into insanity in the back of the Forward Unto Dawn. But that’s something that I’ve already critiqued at length.

This is really the start of what you might call the ‘sorrowful resilience’ dimension of the Master Chief’s characterisation, since Halo 3 is the first time the games really portray him losing something (in this, I do sort of feel that it would’ve been better to begin the game with Chief’s failed assassination attempt on the Keyship). Halo 1 even fell short in this category, as we never really explored his relationship with Jacob Keyes and he had no response or reaction to Cortana’s increasing desperation to get to him.

The idea is that the Chief will always save the day, he will always win, no matter what. We, as the audience, can just take that for granted…

But that comes wholly at the expense of his emotional well-being.

Halo 3 had a lot of things in its story that made Halo 4 inevitable, but the set-up done at the eleventh hour of Halo 3 is perhaps the most subtle and poignant springboard for the direction that 343 decided to take his character in the following game.

But we’ll talk about that next time. To conclude what I have to say on the original trilogy…

To conclude what I have to say on the original trilogy…

The ultimate irony of the “vessel” character is that they’re supposed to be a simple and easy way to have the player slip into their shoes, but these characters get wrapped up in stories that always seem to increase in their emotional complexity. When the stories fundamentally change like that, the characters have to evolve as well.

It’s what backs writers into a corner when they’re determined to keep the player character a vessel for the player, since it breaks the illusion of the immersion they’re going for and you start to question why they didn’t just give the character a proper voice and characterisation in the first place (just look at the difference between Dishonored and Dishonored 2, for instance).

The Master Chief is an interestingly divergent case because he was never a silent protagonist, despite there being this weird misconception from a number of reviewers and gaming journalism over the years that he was.

No, the Master Chief started out as this great confluence of interesting backstory (told through Nylund’s The Fall of Reach, then being followed up by The Flood and First Strike), mixed with the solid character work done by Trautmann, Boren, Soell, and Staten in Halo 1 for him.

From there, Bungie started working backwards…They upped the emotional stakes for the final act of the trilogy while simultaneously making the Master Chief increasingly stoic and vapid.

He awkwardly stands around in cutscenes and doesn’t really do anything, practically becoming part of the scenery while everyone else extensively pontificates about what needs to be done. There are but a few scenes that stand out as an exception.

Clawing for the middle ground with a semi-silent protagonist who you insist the player is the one to detail, despite having an established backstory and a whole game where he is definitively characterised, while also having them be largely inactive in the narrative itself despite upping the emotional stakes… it’s a cocktail for disastrous and inconsistent character writing.

To me, it remains a fatal flaw of Halo 2 and 3‘s campaigns, and was a major contributing factor to the feeling of disparity between the games and the expanded universe. It felt like there were two Halo universes that existed alongside each other, but only one was really willing to meaningfully acknowledge and work with the other. I’m a bit bummed out at myself that the development of this exploration of the Master Chief’s character has tended towards negativity, despite Halo 2 being one of my favourite games of all time and how strongly positive we started with Halo 1…

I’m a bit bummed out at myself that the development of this exploration of the Master Chief’s character has tended towards negativity, despite Halo 2 being one of my favourite games of all time and how strongly positive we started with Halo 1…

Fortunately, the negativity ends here.

Next time, we’ll delve into what Steve Downes has himself described as a “quantum leap” in character writing with Halo 4.

Look forward to a good deal of overwhelming, gushing positivity!

Advertisements Share this: