“A picture is a secret about a secret,

the more it tells you the less you know.”

― Diane Arbus

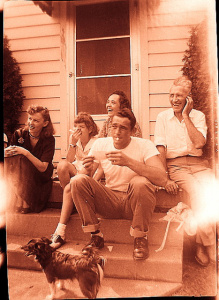

1950s family sitting on the steps (suburbia vintage photo)

1950s family sitting on the steps (suburbia vintage photo)

When my children were very young, it was with a thirty-five-mm camera that my husband and I photographed them. Video is so prevalent now that it seems unreal that the first Camcorder was only released in 1983. We were just starting out and such a device was far beyond our means. Today, making a video is as simple as pulling out your smart phone and pointing it in the right direction. I do it all the time, often with the idea of posting something short on Facebook.

Our lives in this century (in affluent countries at least) are being documented as never before. By the time they’ve entered kindergarten, most children are already the subjects of dozens if not hundreds of hours of video footage. Our voices, movements and body language at every stage of life are available to us on demand. It’s as though nothing is ever lost.

Perhaps that’s what makes photos at once so powerful and so haunting—especially older black and white ones from a time before automated film processing and inexpensive cameras. It’s only memory that can bring their subjects to life.

Imagine, then, stumbling upon a photo printed in an old newspaper and finding the image of the mother you lost when you were three or four years old; barely old enough to even form memories…

This is the starting point of Hélène Gestern’s debut novel, The People in the Photo, a story as intimate as the increasingly personal letters and emails exchanged between its two main characters, Hélène Hivert* and Stephane Crüsten. [*sorry for the confusion that might be caused by the fact that both the author and her protagonist share the same first name]

This is the starting point of Hélène Gestern’s debut novel, The People in the Photo, a story as intimate as the increasingly personal letters and emails exchanged between its two main characters, Hélène Hivert* and Stephane Crüsten. [*sorry for the confusion that might be caused by the fact that both the author and her protagonist share the same first name]

It’s while hunting for the medical records of her adoptive mother Sylvia—now living in a nursing home and suffering from final-stage Alzheimer’s—that Hélène Hivert comes across a newspaper clipping dated June 17th, 1970 (the novel is set in 2007), featuring two men who appear to be in their early thirties, one unidentified and the other named Monsieur P. Crüsten, and a willowy blond woman, identified as Madame N. Hivert. The latter are apparently the winners in that summer’s Men’s Singles and Lady’s Singles at the Amateur Tennis Tournament in Interlaken, Switzerland. But the only thing that matters to Hélène is that she believes she has found, at last, a photo of her mother.

The reader knows from the very first chapters of this epistolary novel that Hélène Hivert is close to Sylvia, who is the only mother she’s ever known; that she works as an archivist in Paris; that her father died three years before the discovery of the photo; that she is an only child, and that she has lived her whole life in the shadow of a sad and terrible secret that has led to the excision of her birth mother from her life.

But the wound never healed, and upon her discovery of the photograph, Hélène places an ad in the Parisian daily Libération, hoping that somebody will come forward with information.

Just when she’s about to give up her quest to find someone who knew her mother, she receives a letter from Stephane Crüsten—a French born biologist whose research takes him to university campuses all over the world—informing her that P. Crüsten is, in fact, his father Pierre. He also identifies the second man as a Russian named Jean Lamiat, who was Pierre’s close friend.

As their written exchanges multiply, Hélène and Stephane’s relationship deepens and flourishes. They eventually meet, several times, and the reader is able to read between the lines and sense a second story in the making.

This is a hard book to talk too much about without spoiling the intrigue, but it’s safe to reveal that Hélène quickly learns her mother’s real name is Nataliya Zabvina, and that she was born to Russian émigré parents who settled in the Russian quarter of Paris, in proximity of Saint-Serge Orthodox church.

Saint-Serge Orthodox Church

Saint-Serge Orthodox Church

Hélène’s visit to Saint-Serge leads her to a tiny old Russian woman named Vera Vassilyeva who carries important memories about Nataliya’s parents and childhood. Meanwhile, Stephane tracks down Jean Lamiat’s notebook, which provides other missing pieces.

The picture that emerges of Nataliya Zabvina, her husband Michel Hivert, Pierre Crüsten and Jean Lamiat is more than just tragic. Following her encounter with Vera Vassilyeva, Hélène wonders:

“The more I hear about Nataliya, the deeper the impression I form of her as a joyful, happy well-loved person. What can have happened, what crime can she have committed to find herself so entirely wiped from family memory?”

Her cry echoes the experience of many adopted children in the way it expresses a sense of amputation from a phantom past, a longing for blood connection, and the need to fill in the blanks of one’s own origin story. Hélène describes the impression of “shadows becoming flesh”, and finds herself saying out loud, in Russian, to Vera: “I am Nataliya Zabvina’s daughter.”

The Russian Quarter, Paris

The Russian Quarter, Paris

The People in the Photo is a thoughtful book about the terrible things we do to each other when love goes wrong. It’s an exploration of the place where sorrow and vindictiveness meet. It’s a reminder of the indelible taint of secrets that poison families as surely as if they had settled upon radioactive ground, and a moving illustration of how the consequences of parents’ choices are laid upon their children.

“Memory is the diary we all carry about with us.”

― Oscar Wilde

“Let us not burthen our remembrance with

A heaviness that’s gone.”

― William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Advertisements Share this: