One could look at The Post, the latest from veteran director Steven Spielberg, and see a current and scathing indictment of executive authority to undermine freedom of speech vis a vis journalism, a critique of modern political decorum by way of an examination of the past.

Ignoring the politicization of this message, the grand-standing done in the final 30 minutes of this film, in which this message is ultimately presented (the whole movie has led us, quite transparently, to this message), makes for such a repetitive hammer-on-nail motion as to crumble the artifice that has made the film an exciting watch up until that point.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

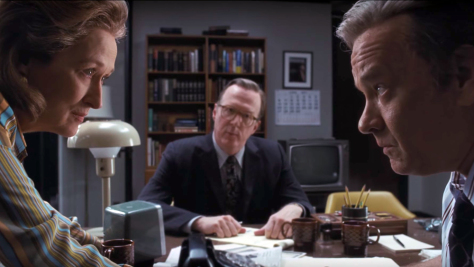

The Post follows the publication of the Pentagon Papers, government documents that exposed secrets about the Vietnam War that were held through four presidential administrations, by the Washington Post (and the New York Times, but they’re less important here). Mainly, it focuses on the paper’s publisher Katherine Graham (Meryl Streep) and editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks), plus a laundry list of characters played by popular character actors.

Acting certainly is no detriment here. The consistency by which Tom Hanks glibly remarks “no s**t” is enough to sell his role. The deep cast list the includes former comedy duo David Cross and Bob Odenkirk, Sarah Paulson, Tracy Letts, Bradley Whitford, Jesse Plemmons, Bruce Greenwood, and Michael Stuhlbarg was generated as to not disappoint. Their characters act as monochrome pawns, but indeed they do not disappoint.

But it is Streep who brings the strongest performance of the film, which is no surprise to anyone who’s been watching movies for the last four decades. Her character’s arc is also the most fully realized—Graham’s initial timidness to step out of the shadow of the paper’s all-male board shed by the end of the film—which helps to make her appearance in the film more magnetic than the other cast members.

What is surprising about The Post, a film dedicated to the idea that the only action that a film needs is powerful dialogue, is that it is visually dynamic. This can more often than not lead to blocking and staging that is unnatural—at least one time just downright silly—where characters walk circles around each other in order to allow for motion in what would otherwise be a static, conversational scene.

One need only look at the scene between Odenkirk and Plemmons, there bodies over-dramatically lurching around each other and turning round and round as they discuss a journalistic source, to understand this exaggeration of movement.

Aside from this scene and a handful of others, though, the camera work by Janusz Kaminski sells this exaggeration exquisitely. Kaminski’s camera ducks in and out, bobs and weaves, pans and tilts in ways that keep scenes from reading entirely static or overly-staged.

The Post shows plenty of promise—certainly showing that Spielberg remains at the top of his form. It has a newsroom energy to it that pulsates as the characters push dangerously close to their deadline. However, it is as the film reaches this narrative deadline that The Post starts slipping away from the propulsive, talky drama that it has been up to this point.

Instead, it slips closer to being an Oscar-baiting piece on modern journalism, a hypothetical look at what could happen if freedom of the press is challenged by an American president. In trending this way during the film’s final act, characters become mouthpieces (as opposed to characters) and the drama of the historical moment loses traction. As a result, the good will that the film has built up leading into this final act becomes a fleeting memory. A fond memory, certainly, but one that must be extracted from the thesis statement that is trumpeted in sforzando just before the end credits fade in.

The Post: B

As always, thanks for reading!

Like CineFiles on Facebook for updates on new articles and reviews

Check out my page on Letterboxd

—Alex Brannan (@TheAlexBrannan)

Advertisements Share this: