As a tenth-grade English teacher, I always began the year with personal narrative. My students and I created life maps, compiled writing inventories, discussed pivotal life moments, read mentor texts, drafted, revised, and learned each other’s stories and the stories of our own writing processes. We began with Cynthia Rylant’s When I Was Young in the Mountains and George Ella Lyons’s Where I’m From, moved through students’ own childhood memories, and worked our way into more advanced memoirs, like Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s Colored People and Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle. At each step, we wrote. We asked questions about our own stories and the moments that shaped our lives: How is my experience like his, hers, yours? How is it different? How did it make me who I am? What makes a good story?

As a tenth-grade English teacher, I always began the year with personal narrative. My students and I created life maps, compiled writing inventories, discussed pivotal life moments, read mentor texts, drafted, revised, and learned each other’s stories and the stories of our own writing processes. We began with Cynthia Rylant’s When I Was Young in the Mountains and George Ella Lyons’s Where I’m From, moved through students’ own childhood memories, and worked our way into more advanced memoirs, like Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s Colored People and Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle. At each step, we wrote. We asked questions about our own stories and the moments that shaped our lives: How is my experience like his, hers, yours? How is it different? How did it make me who I am? What makes a good story?

Craft and Convention

To be sure, practicing story helps us meet academic standards. It requires examination of imagery, chronology, setting, detail, dialogue, action and pacing, and exploded moments of importance (eliminating the bed-to-bed story). On a practical level, work in personal narrative writing helps writers prepare to tell other stories: those embedded in lab reports, research findings, college applications, or when a job interviewer asks “Tell me about a time when…” Teaching narrative, especially memoir, helps students see the important moments that make up the themes of their lives. As Nancie Atwell explains, narrative memoir teaches us to “figure out who we were, who we’ve become, and why.” Teaching narrative has the capacity to deepen self-awareness, other-awareness, and empathy. When we began to read and write stories in my classroom, I often found that students began to make connections to one another. They found common ground over shared experience, and this helped my students see similarities even among their differences.

To be sure, practicing story helps us meet academic standards. It requires examination of imagery, chronology, setting, detail, dialogue, action and pacing, and exploded moments of importance (eliminating the bed-to-bed story). On a practical level, work in personal narrative writing helps writers prepare to tell other stories: those embedded in lab reports, research findings, college applications, or when a job interviewer asks “Tell me about a time when…” Teaching narrative, especially memoir, helps students see the important moments that make up the themes of their lives. As Nancie Atwell explains, narrative memoir teaches us to “figure out who we were, who we’ve become, and why.” Teaching narrative has the capacity to deepen self-awareness, other-awareness, and empathy. When we began to read and write stories in my classroom, I often found that students began to make connections to one another. They found common ground over shared experience, and this helped my students see similarities even among their differences.

Connection

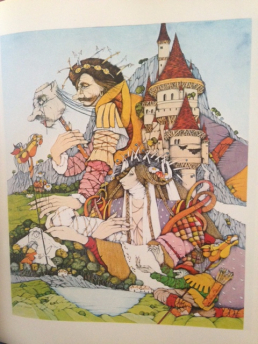

More than academic skill and empathy, however, movement into story moves us into primal notions of what it means to be human. An ancient practice, storytelling is an act of ritual that can connect us with something bigger than ourselves and our classrooms. Von Franz discusses story, fairy tales in particular, as movement toward wholeness. This sense of the universal in the personal became real to me when I taught college writers under the supervision of behatted storyteller and horseman Dr. Joseph McCaleb at The University of Maryland. Working with students in his “Good Stories course,” we moved the archetypal imagery found in traditional stories through a process of digital composition that allowed us to consider the particular in the public, the personal in the universal.

<

>

The narratives that we produced, by the end of the course, were digital stories that centered the composer in the composition and the composition in the world in order to advance a sense of peace and justice. They used sound, image, diction, detail, and, of course, story, to reach toward a greater meaning. Teaching narrative in that way was transformative for students, as well as for me as a teacher–and not just in terms of pedagogy. Inasmuch as teaching is storytelling, this was a significant moment in the story of my teaching life because I was discovering the stories inside me alongside my students as they found their own words. I was able to feel the potential for changing myself, my students, and my world, echoing Dr. McCaleb’s creation story, “as the tiny acorn can feel stirring within itself the energy of the mighty oak.” Narrative has the power to connect us to others across space and time; it can reveal our humanity.

Classroom Applications

But perhaps our goals for the students in our classrooms need not be quite so lofty. In the coming weeks, as you plan your first units, I challenge you to infuse narrative, even if just to teach the standards. Try telling a story of a significant moment on the first day of class; read a story together to exemplify a course theme; or when teaching research, work through a story as qualitative evidence of lived experience. Use auto-ethnography, documentary, reportage, memoir. Create multi-layered stories: picture books, audio files, digital videos. Our students deserve rich texts–ones they read and ones they create.

But perhaps our goals for the students in our classrooms need not be quite so lofty. In the coming weeks, as you plan your first units, I challenge you to infuse narrative, even if just to teach the standards. Try telling a story of a significant moment on the first day of class; read a story together to exemplify a course theme; or when teaching research, work through a story as qualitative evidence of lived experience. Use auto-ethnography, documentary, reportage, memoir. Create multi-layered stories: picture books, audio files, digital videos. Our students deserve rich texts–ones they read and ones they create.

What story do you yearn to share? What tales will you tell with the writers in your rooms? How will you use narratives in your teaching this year?

NWP@WVU Co-Director Sarah Morris teaches undergraduate writing courses and is the associate coordinator for the Undergraduate Writing Program at West Virginia University. Her research interests include human science phenomenology, embodiment, writing process, and student-centered teaching.

Advertisements Share this: