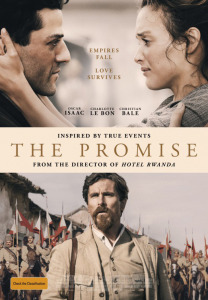

War and military conflict have always proven fine fodder for cinema stories and there has been upwards of 200 films made capturing the horrors and heroics of World War 1 since the conflict ended in 1918. Of these, less than 20 have focussed on the Armenian Genocide of 1915 that saw more than 500 000 people murdered at the hands of the Ottoman Government (the exact number killed is unknown but could be in excess of 1 million). If nothing else, The Promise serves as a timely reminder of how intolerance of ethnic or religious difference can result in devastating consequences for marginalised groups. Directed by Terry George (Hotel Rwanda), The Promise is a film in two parts; an opening portion that focuses on a love triangle between a budding doctor, an American journalist and an artist who has returned from Paris following the death of her father, while the second segment focuses on the efforts of the Ottoman forces to eliminate the entire Armenian population. This attempt to eradicate an entire nation of people is a story that needs to be told and the casting of Christian Bale and Oscar Isaac makes the film accessible to a mainstream audience, so it is a shame that so much time is wasted on the romance narrative, rather than offering a more in-depth examination of the historical context of the events and the political machinations that resulted in human suffering on a grand scale.

Isaac (Ex Machina, Inside Llewyn Davis) is Mikael Boghosian, the apothecary (pharmacist) in a village located in what is now southern Turkey, a community in which Turkish Muslims and Armenian Christians have lived together harmoniously forever. Literally within the first five minutes of screen time, Mikael has betrothed himself to a local woman, used her dowry to pay for a place in medical school in Constantinople, taken up residence in the city with his wealthy uncle and fallen in love with Ana (Charlotte Le Bon), who has arrived back in town after an extended period living in with Paris and has journalist Chris Myers (Bale) in tow. Ana’s time in Paris is emphasised purely, it would seem, to justify her French accent and the fact that everybody speaks English is something that obviously detracts from the authenticity of the story. As anti-Armenian sentiment spills into the streets, Ana and Mikael find themselves in danger and it isn’t long before Armenian residents are being rounded up to be executed or sent to work in labour camps, which is when the movie gets interesting.

With his hopes of a medical career dashed and now on the run from the authorities, Mikael returns home, only to find the village and its residents under threat. There are some harrowing moments as people are slaughtered en-masse for no reason other than their Armenian heritage and their determined, but ultimately doomed, efforts of resistance in the face of overwhelming odds is a very timely reminder of how it comes to be that people can be forced to flee their homeland purely as a means of survival. The difference in this instance is that those lucky enough to survive were, quite rightly, treated as victims of oppression and assisted in their efforts to flee, which is a far cry from the way we treat refugees today. It is hard to fathom how a soap opera-ish love triangle came to be the centre of the story when what’s happening elsewhere is so much more interesting. There are numerous people whose stories offer plenty of narrative potential (such as the priest providing safe passage for Armenian children at considerable risk to himself), but with so much time dedicated to the love story, there is little time to explore any of the characters in any depth.

The script, penned by George and Robin Swicord (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button), is underwhelming and prone to many moments of melodrama that gives a quality cast, which includes Shohreh Aghdashloo as Mikael’s mother and both James Cromwell and Jean Reno in very small roles, very little to work with. However, the latter stages do compensate somewhat for the syrupy cliché-ridden romance. There are many who declare that James Cameron’s Titanic only gets interesting when the boat begins to sink and a similar claim could be made here. Suffer through the soppy stuff and a far more engaging story emerges.

Share this: