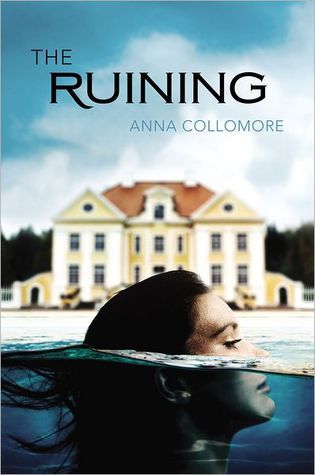

Standalone, Razorbill, 2013, 313 pgs.

Annie finally feels like her life is beginning. She’s moving away from her run-down, broken home in Detroit to go to college in California and make something of herself. Moreover, she’s moving away from her awful past and into a taste of what she hopes is her future; she’ll be working as a nanny for and living with a rich couple who have the sort of life she’s always dreamed of. Life in California seems wonderful, too. Walker, the father of the family she’s staying with, is funny and easygoing, Zoe, the little girl she’s watching, is sweet and adorable, and their house is beautiful, like something out of a magazine. There’s even a cute boy next door and the excitement of finding herself in her classes to round things out for Annie. So if the mother, Libby, is a little nit-picky and gets worked up over tiny things, that’s fine, right? She’s still fun to be around, and attentive, and seems to think of Annie as a little sister, even if she sometimes does strange things. Ok, so maybe it’ll be a little tougher than she thought it would, but Annie can’t throw this chance away. She just can’t.

I’ve read quite a lot of smart books; it always brings me a little pang of joy when an author does something clever with the characters or plotting or references. I’ve read quite a lot of stupid books as well, sometimes unintentionally, but also because sometimes everyone needs to relax with something fun and light.

I don’t know that I’ve ever read something that is somehow both at the same time.

I realize that’s sort of an odd statement to make, but this book is pretty clearly split on how well it was thought out. There are parts of this that are done beautifully, where the author obviously did detailed, studious research, and there are parts of this where things seemingly happen only because it’s convenient to the narrative.

To start, though, I will say this to the book’s credit: the parts that don’t really fall into either of those categories are generally good. The characters are engaging and decently three dimensional, and the prose is pretty evocative and beautiful. If you’re not going to be bothered by some plot contrivance then you’ll probably be perfectly fine with this.

Similarly, the major driving theme is really well-researched, especially for a YA novel.

A novel about the way abuse can work its way into your brain and make you think that the only problem in a situation is you could have easily been hackneyed and melodramatic, but here nearly every part of the novel that works toward exploring that side of things is well drawn.

What our villain, Libby, is doing to Annie isn’t exactly subtle, but you do really get the sense of her deliberately fishing out another person’s weaknesses and using them. You do really get the feel of Annie blaming every little thing on herself, because obviously no one would react that strongly if she hadn’t done something wrong. You are confused along with her as she begins to doubt her own senses and memories. It’s clear Collomore looked into how an abusive situation works and tried to do as much justice to it as she could.

And Annie herself is set up very well, with regards to that. It’s made clear at the beginning of the novel that she comes from a sort of neglectful background anyway and has some mental issues along the lines of PTSD and self hatred from her sister’s death when she was younger. She’s fresh from escaping the first and has never really dealt with the second. These are all things that make her susceptible to Libby’s manipulation in the first place, and, when she trusts Libby with them towards the beginning of the novel, they become hinge points for Libby to work her way in.

Again, this is all set up fairly cleverly. There are parts of this book that are smart.

Also again, there are unfortunately parts of this book that are stone-cold stupid.

Like Collomore’s tendency to make her lead behave in irredeemably dumb ways when the plot calls for it. I never expected Annie to see through the abusive behavior of someone she trusted and liked, especially when she saw this job as her one chance to get away from her awful life and Libby’s craziness and impositions were introduced slowly. I did, on the other hand, expect her to be a reasonably intelligent person who could put two and two together from easily offered pieces of information.

There were several key points along the way that Annie really should have figured out sooner. For at least one of them I’m not even sure if you could rightfully call it plot contrivance, because knowing it wouldn’t have broken Annie’s mindset of “Libby is good and giving me far more chances than I deserve,” so it wouldn’t have really affected how things played out. Knowing it might have even given her more sympathy for Libby.

I’m not sure why Collomore decided to dumb down here character there, except as for a cheap twist that didn’t work because it was too obvious. I suppose that’s a sort plot contrivance too, though.

And in some ways this tendency toward plot contrivance breaks the typically good characters. Annie’s supposed to be a smart person, and fairly fighty. She spends most of the novel trying to keep herself up out of the swamp of manipulation, even as she’s slowly slipping down. Then, at the end, the author completely throws out what has been some careful work with this character’s arc in order to have her break down completely, seemingly overnight.

And this example is plot contrivance in a way that the former might not be: this needed to happen for the love interest to have motivation to actually interfere in the situation. So, complete breakdown from a character who really didn’t seem that far gone.

It’s just little pieces of sloppiness that destroy something that could have been really interesting. Like some other things I’ve read, Collomore really needed to take the careful thought she put into taking apart an abusive situation and seeing how it worked, and expand it out to the other pieces of her novel.

Advertisements Share this:

![[178].png](/ai/061/918/61918.png)