With pieces selling for high prices, a broad skill set and long resume of work, Takashi Murakami is a leading figure in the world of Japanese postmodern art. His work is a pure representation of Japanese history and culture. His Superflat theory and movement in particular, the fundamental basis of most, if not all of his work, is uniquely Japanese and could not be replicated in any other culture. It focuses on demonstrating a post-war Japan, battered and bruised following a drawn-out defeat at the hand of America and the Allies, including the two infamous nuclear bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Murakami, in his 2005 book companion to exhibit Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, defines Superflat as “a flattened surface, the working environment of computer graphics, flat-panel monitors, or the forceful integration of data into an image.” His view of Superflat as a flattened out reality and a frustrated, nostalgic, disarmed, Westernized Japan helps to clarify his art, which at first glance seems bright and cute, if not a bit weird. To demonstrate this vision, I want to focus on three pieces, 1999’s Supernova, 2002’s Tan Tan Bo Puking, and 2012’s the 500 Arhats.

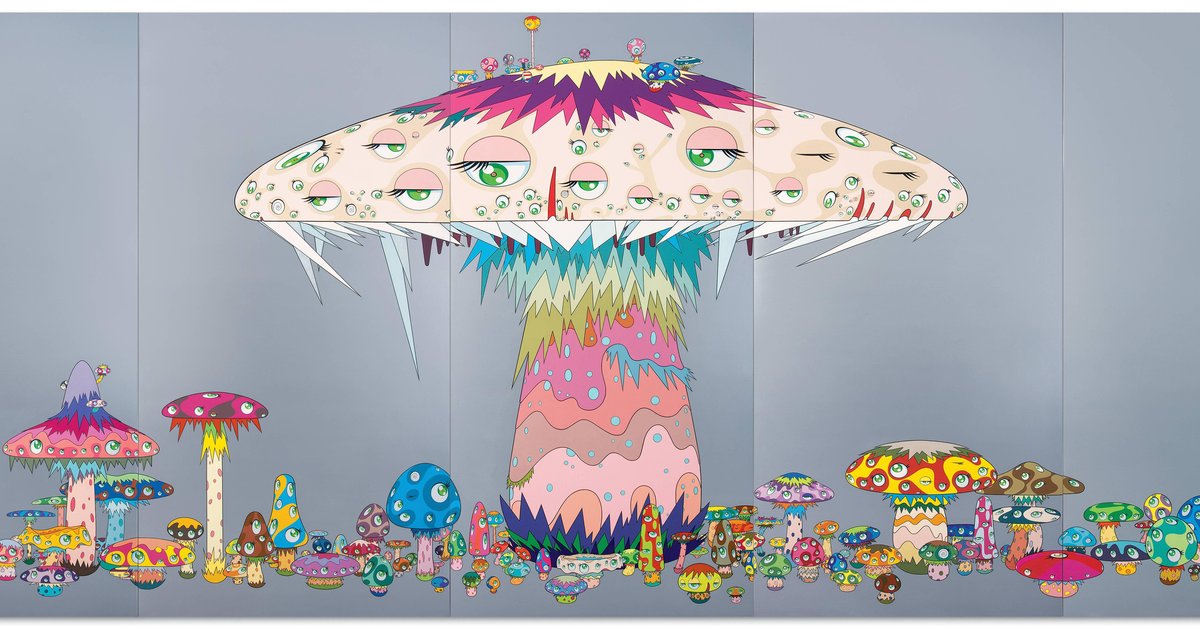

Supernova is the perfect depiction of the tragic events the Japanese suffered from involving Big Man and Little Boy through the “cuteness,” flat lens of postwar Japan. In many artistic creations, implied lines are used to portray a level of depth, a third-dimensional space, especially when paired with the use of shading. However, Murakami shirks this for vibrant, flat colors and thicker lines, which flatten the piece out and make it pop. The focal point of the piece is the large scale mushroom in the middle that towers over the others, which looks eerily similar to a nuclear mushroom cloud. This is one of the events that set things into motion. It provides the most off putting and fascinating juxtaposition between worlds. A terrifying event is taken and made to look cute and harmless, with round eyes and thick lashes peppered all over the mushroom head. To me, seeing Murakami create this work just highlights the transformative, defanged post-war Japanese attitude and culture. At first glance and without context, it’s easy to perceive Supernova as a cute postmodern pop-art, and possibly kitschy piece. But it’s more, it’s the statement of a frustrated man representing his people, a society who has “given up”.

The second piece, Tan Tan Bo Puking has a stronger personal slant than the first one. In his talk with curator Michael Darling for the exhibit The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg, Murakami talks about his life situation during the creation of Tan Tan Bo. At the age of 32, he got gout due to a sodium-rich diet of noodles, as well as having bad habits like constant lack of sleep and smoking. It got to the point where he thought about the inevitability of age and death. With this personal anecdote in mind, it is easier to make an interpretation of this piece. It’s dual layered, with the first layer being the cute but weird pop culture piece at face value and the second involving Murakami’s life at the time. Like the last piece, contrast is created through the use of thicker, explicit lines and flat, bright colors over implied lines and shading. This stylistic choice shows even his suffering as merely just a crazy, weird modern art spectacle. The focal point, Murakami’s Mickey Mouse-esque signature character Mr. DOB, is dying, puking up anything imaginable. However, he still tries to hold onto life, still wants to develop and grow. It’s morbid and depressing, but the need for the abstraction of this content from it’s round eyed, artsy, cute exterior makes it hard to discern these emotions. This second layer can be expanded and interpreted through the plight of the Japanese people and the state of their country. While not explicitly stating Japan is dying, Murakami uses DOB as an icon to demonstrate the struggle of Japan to grow past it’s two dimensional trapping, it’s defanging under the hand of the West, particularly America. Murakami manages to portray his own artistic and mortality based uncertainties, and by extension the suffering of Japan.

This is only a part of the 100-meter long painting.

Finally, the 500 Arhats signified Murakami’s refocusing on Japan. After the magnitude 9.0 Tōhoku Earthquake struck, which was followed by the Fukushima Plant Disaster, Japan was in a state of disarray and turmoil. This shook Murakami up and pulled him back into reality. By creating the 500 Arhats, Murakami was making a statement to the Japanese people, his people. In Arhats, Murakami’s visual stylings are similar, and the Superflat motif is still there, but the interpretation is different. This time, the foregoing of implied lines and shades for brightness and flatness serves to bridge the Japanese past and modern Japan, as well as its poppy, cute, mainstream stylisations and rich history of traditional art funneled through Murakami, in order to reach into Japan’s heart and offer healing. It uses a built up representation of the 16 Arhats, who were monks that devoted their life to aiding and healing human suffering (Buddhist Sages). He also uses the depictions of arhats painted by Kano Kazunobu, a traditional Japanese artist back in the Meiji era. In a way, Arhats can be perceived as Murakami reflecting on himself, his life and success, his Japanese identity. Compared to works like Supernova and Tan Tan Bo Puking, Arhats has a more ethereal, awe inspiring atmosphere to it. It intertwines the ideas of mortality, religion, and the past to create commentary and parallels to that point in time. With Arhats, Murakami hones in on Japan’s legacy and mentality, creating a piece that portrays Japan’s somberness.

Through these three pieces, and a multitude of others in his long tenure, Murakami lays out his perception of Japan as this super flat nation, disarmed after the war and lacking any sort of distinction of high and low, commercial art. The Japanese are a broken down people, trying to survive on a Westernized, economic, superficial world. The juxtaposition of weird, cutesy, commercially fashioned and western-styled pieces and the message and Japanese identity behind that exterior really helps to create a stronger impact. Murakami and his Superflat theory really helps put into perspective not the exact vision of Japan, but an alternative reading and viewpoint of a struggling society. Murakami, for all his eccentricities, continues to provide the exploration and expression for his world, and that is really important.

(This piece was written as a final paper for a comprehensive art course.)

References:

Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture. Murakami, Takashi.

https://www.ft.com/content/fd513f92-142a-11e5-abda-00144feabdc0

https://vernissage.tv/2010/09/20/murakami-versailles-interview-with-takashi-murakami/

http://www.jca-online.com/murakami.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5R4cYGqqq0s

https://vimeo.com/221012425

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-WYgczXBfA

http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/history/arhats.htm

Advertisements Share this: