I. THE WALL

“In Rome on the Campo dei Fiori

baskets of olives and lemons,

cobbles spattered with wine

and the wreckage of flowers.

Vendors cover the trestles

with rose-pink fish;

armfuls of dark grapes

heaped on peach-down.

On this same square

they burned Giordano Bruno.

Henchmen kindled the pyre

close-pressed by the mob.

Before the flames had died

the taverns were full again,

baskets of olives and lemons

again on the vendors’ shoulders.

I thought of the Campo dei Fiori

in Warsaw by the sky-carousel

one clear spring evening

to the strains of a carnival tune.

The bright melody drowned

the salvos from the ghetto wall,

and couples were flying

high in the cloudless sky.

At times wind from the burning

would drift dark kites along

and riders on the carousel

caught petals in midair.

That same hot wind

blew open the skirts of the girls

and the crowds were laughing

on that beautiful Warsaw Sunday.”

Czeslaw Milosz, “Campo dei Fiori”

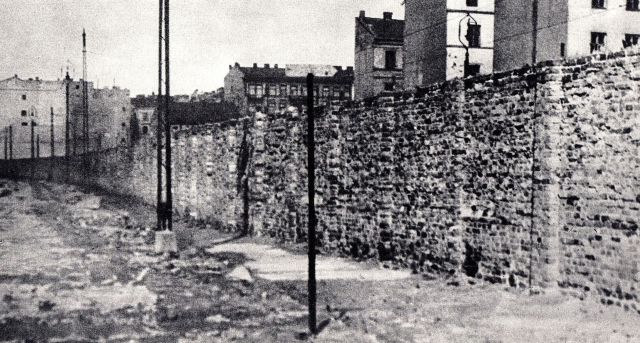

In this touching poem, the brutality of the Nazis liquidating the Warsaw Ghetto is happening behind the wall, sheltering the potential onlookers from the atrocities. In Polin, the Warsaw Museum of the History of the Polish Jews (see below for the meaning of “Polin”), these words written by Chaim A. Kaplan struck a poignant chord with me:

“We are imprisoned within double walls: a wall of brick for our bodies, and a wall of silence for our spirit.”

The Jewish story is no longer surrounded by the wall of silence. The central thought of The Story of the Jews, beautifully imagined in the opening credits to that magnificent documentary by Simon Schama, is that the people who were left with nothing started living in the house of words. Their story and their holy book, the Torah, was sustaining them. The thought is strengthened in his book The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words. Those who have found their words, have found themselves.

II. THE PALM TREE

The 15-metre tall artificial Palm Tree at a busy roundabout in the centre of the city may seem an unlikely symbol of Jewishness. It stands at the intersection of the two most representative streets – Aleje Jerozolimskie (Jerusalem Avenue) and Nowy Swiat (New World Street). The palm tree, reminiscent of the palms of Jerusalem, marks the absence of the Jews in the city, which was previously their settlement. Wikipedia explains why the Jews chose Poland as their home:

“Some Jewish historians say the Hebrew word for ‘Poland’ is pronounced as Polania or Polin in Hebrew. As transliterated into Hebrew, these names for Poland were interpreted as “good omens” because Polania can be broken down into three Hebrew words: po (“here”), lan (“dwells”), ya (“God”), and Polin into two words of: po (“here”) lin (“[you should] dwell”). The “message” was that Poland was meant to be a good place for the Jews.”

The palm is an ancient symbol of life, victory and fertility, and the Christian symbol of resurrection. It has both masculine and feminine connotations, making it a symbol of totality. In the Dictionary of Literary Symbols, Michael Ferber wrote, “The word “palm” (Latin “palma”) is the same as that for the palm of the hand: to the ancients the tree resembled the hand, the branches or fronds looking like fingers.” In the web of symbolic meaning, another association was solar, the branches of the palm resembling the rays of the sun. Apollo was born under the palm tree. On the feminine side, both in the Odyssey and in the Song of Songs, the beauty of women is compared to the beauty of palm trees. Ferber adds, “The Hebrew word for palm, tamar, was and remains a common girl’s name.” “Phoinikos”, the Greek word for the palm, brings to mind its association with rebirth.

There is something very triumphant, exultant and joyful in this ancient symbol positioned in the middle of a busy roundabout in the part of Europe where palms do not belong. As the symbolic palm unites the opposites, so does this one bringing two worlds together.

Advertisements Share this: