Note: This installment of Urban Fantasy 101 deals with racism and slavery and was written in April for a grad school assignment.

People – writers and otherwise – romanticize a lot of weird (and beyond problematic) shit.

From novels about Thomas Jefferson’s clearly inappropriate and abusive relationship with his young slave Sally Hemmings (who was his wife’s younger half-sister, by the way) to the way that every year we get a handful of media telling the tale of members of hate groups (like the Klan or Nazis) falling in love with the people they have been oppressing, sometimes it feels like you can’t sneeze without spitting on media that tackles history from a point of view that feels like it does more romanticizing than criticizing.

So for this installment of Urban Fantasy 101, I’ll be tackling the way that Southern Pride plays out in the genre and how writers need to stop romanticizing a period of history that couldn’t have existed without enslaving Black people.

I’ll be talking about authors trying to showcase what they love about Southern culture and how that often goes hand in hand with failing at being respectful to the Black people who were brought to the United States against their will and whose subjugation was integral to the development of “Southern pride”.

First, let’s talk about Southern pride.

I think of Southern pride as something with many faces.

On one side, you have the picturesque imagery of someone sitting on a porch in an ancient rocking chair drinking freshly squeezed lemonade while crickets chirp. On another, you have Confederate flags and reenactments of the “War of Northern Aggression” where things happen “as they should have” and the South wins. On yet another face, you have the clueless pageantry of plantation weddings and the very idea of the Southern Belle as a life goal.

Of course, it’s not inherently problematic to celebrate your history or even incorporate it into your books, but here’s the thing: the way that many folks conceptualize Southern Pride tends to rewrite and whitewash Southern history in the process of lifting up the South.

Back in the day I was a huge Hart of Dixie fan.

(I’d follow Rachel Bilson all the way into hell, thank you very much, and the show looked adorable when it first aired on The CW back when I was an undergrad.)

However, so much of the show basically served as a love letter to the Deep South that overlooked many of the problems inherent in writing that kind of narrative. It made the idea of the Southern Belle accessible instead of awful without ever once taking into consideration why these white women could and did try to memorialize this sort of stereotypical Southern feminiity.

There were maybe two recurring Black characters and while the one main Black character was also the mayor of Bluebell, the show didn’t dare to get intersectional with his plotlines so he was almost always framed through a white Southern gaze.

And Hart of Dixie was basically a romantic comedy with medical drama elements.

Imagine what kind of Southern experience, the portrayals of Southern Pride, we can and do get in the Urban Fantasy genre, a genre that already hinges heavily on allegories as stand ins for marginalized people who experience forms of racism like homophobia or racism… It’s not pretty.

On its own, in literature and otherwise, Southern Pride isn’t a huge problem. Neither is remembering the history of the places your characters come from. In Gail Z. Martin’s Deadly Curiosities, the main character describes the city that she lives in in clear, critical terms:

Heck, if you believed the guides on the nightly ghost tour carriage rides, every house, garage, and alleyway was haunted. Some of that made for good fun for the tourists, but there was an uncomfortable undercurrent of truth. Charleston was a beautiful city, but it had been built on the blood, toil, and misery of African slaves.

This is the kind of city description that doesn’t actually happen very often. Later on in this same book, the main character is introduced to the Gullah people and their relationship with South Carolina and magic over the generations. (Which is a small thing to be happy about, I know.)

And seriously, let’s look at Beyonce’s Lemonade visual album, a work that talked about her pride in her heritage while directly confronting the legacy of slavery and misogyny that led to her existence. You can have pride and be critical of the thing you’re proud of. It’s not that difficult.

There’s a difference between the Lemonade visual album which does tackle Blackness and the history of slavery in what is largely a respectful way and then something like Sophia Coppolla’s latest all-white “feminist” wonderland or The Originals/Vampire Diaries franchise and shared universe where Black characters are implicit – and sometimes explicit in the case of Marcel and Klaus – slaves to white vampires and the South is held up as something glorious(ly white and pure).

Right now, I’m reading Attica Locke’s The Cutting Season for my Monday night class and this is a book set not just in the South, but on a former slave plantation that has been turned into a historical landmark and park. They do tours, performances, and the occasional wedding.

Locke presents the South and this aspect of Southern Pride – not just that people can go to plantations as museums, but what they do in them – as a fact of life. The main character Caren is the manager of the plantation-park and we see her reality as well as the experiences of other Black people who work as the plantation’s “slave” reenactors. The story itself is clearly about the slowly evolving relationships between race and class on this setting but it also doesn’t forget to look backward even as it moves forward.

At no point does Locke make you feel as though she’s romanticizing anything in this book. In an interview with NPR, Locke even talked about the experience that she had while being on the plantation that served as the inspiration for her book, saying that,

“You’re driving through rural, working-class Louisiana poverty. And all of a sudden, along the Mississippi, this incredibly majestic house, these beautiful grounds with these arching oak trees, just kind of rises up. And I felt this tear inside — there’s no way to not feel the beauty of it because it is so stunning. But it also kind of made my stomach turn, because of what it represented. […] And I and my husband pause, and I started crying. I didn’t understand what my presence there in 2004 meant. I was there with my white husband, it was an interracial couple getting married — I couldn’t decide if the point of us being there was an act of healing, or if there was something sick about turning a plantation into an events venue — that you were stomping on the history, so to speak. And there’s a way in which I do think that all of this is a metaphor for where we are as a country, where we’re kind of caught between where we were and where we’re going.”

You might be reading this and wondering why I’m dedicating so much time to this book that isn’t even an urban fantasy book.

I want to use Locke’s work to serve as a “how things could be” for the genre because of the way that she writes not only Blackness and Black history, but the experience of balancing this past against the pride people want to have over places that directly connect to centuries of Black bodies suffering.

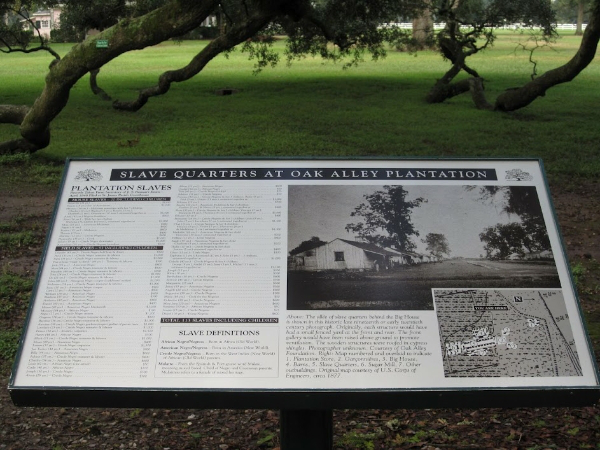

List of Enslaved Black People at Oak Alley Plantation (from Attica Locke’s gallery for The Cutting Season)

Now for the most part, Urban Fantasy series tend to skim over the realities of slavery or its aftereffects. I get it. The TransAtlantic Slave Trade is one of the most devastating and disruptive periods in human history. You literally don’t have to explain to me how anxiety inducing it is to even acknowledge that it happened in your fiction because of how easy it is to screw it up and hurt people.

I know.

I’ve been there.

The problem though, is that because of the genre’s reliance on super specific allegories for oppression (check out my other UF101 posts for the heads up on those), even though authors from different backgrounds feel uncomfortable tackling slavery and the effects it has on Black people across the diaspora to this day, they still use slavery and its effects in their series.

Just…

Not usually in a way that relates back to Black people.

Now I’ve read a ton of Urban Fantasy series. Some handle Blackness very well, balancing the supernatural against a backdrop of diverse characters whose identities are represented in their stories.

Others… don’t.

In earlier installments of this series, I’ve mentioned a major problem in the genre is that you’re more likely to come across vampires and werewolves than people of color in the genre’s presentation of cities where people of color tend to serve as the majority of the population. At no point in your urban fantasy work should New Orleans have been as white as Anne Rice (and countless other writers who followed in her footsteps) wrote it to be over the course of over the course of the past forty years.

That’s just a fact.

Now, this brings us to the aftereffects of slavery in Urban Fantasy.

A majority of works in the genre, simply don’t talk about race as we understand it now, but it’s important to keep in mind how the genre typically talks about the history of slavery and how it affects characters.

For that, I turn to Charlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire Mysteries series.

While the main series ended four years ago, I think it’s an excellent example of how a writer in the Urban Fantasy genre can make missteps when it comes to handling Southern Pride and supernaturals. In the book series, set in the Deep South, few Black characters show up and the locales of the series – primarily in the small town of Bon Temps, Louisiana – are such where segregation is still practiced in one form or another.

In a 2009 feature, we find out that Harris grew up in a tiny Mississippi town that didn’t have an integrated high school until 1969 when she was about to graduate.

This experience of segregation is shown in the book series – where it’s implied that there are separate funeral homes in Bon Temps (Harris calls it “tradition rather than racism” as if the two concepts aren’t inextricably linked) – and in the television series where characters of color are shown living on the outskirts of Bon Temps society and having trouble integrating into the mainstream (same as the mostly white vampires in the franchise).

Bon Temps society, by the way, is heavy with Southern Pride and the sort of respectability politics that seem like they’d be perfect if placed back into the 1950s. In the first episode of the show and in the first chapter of the series’ first book Dead Until Dark, Southern Pride shows up in two separate ways.

First, when main character Sookie Stackhouse tells her younger brother about the vampire that she saved from a pair of redneck vampire drainers, immediately her brother’s thought is about the neighboring towns that don’t have vampires in them. It’s a point of pride in small Southern towns to one up one another over things that they have or don’t have. Be it a new football field, a homegrown celebrity, or a prize-winning pumpkin at a local fair, a huge (but frequently benign) part of Southern Pride is one-upmanship and rubbing success into other people’s faces.

Only, the point of pride in Bon Temps in the start of the series is a vampire.

For me, this fascination with having access to a vampire and using it to gain social/cultural capital with other towns in the surrounding area has a lot to do with an aspect of Southern Pride that seems petty at first: having pride in your town, and in your heritage, and in the things that your neighbor from ten miles south can’t possibly have.

This conversation between Sookie and Jason Stackhouse about the new undead arrival to their tiny town leads to what I feel is the most insidious aspect of how Southern Pride works in media. At the end of their conversation, the Stackhouses’ grandmother can’t stop thinking about the vampire that Sookie saved and the worth that a vampire potentially old enough to have lived through the Civil War has to her, a charter member of the Descendants of the Glorious Dead.

Seriously, a majorly annoying aspect of the way Southern Pride is portrayed in media is the fixation on rewriting the Civil War as the unfortunate end to a glorious Southern society.

Here’s the first scene in part:

Once we got off the topic of Maudette’s murder, lunch went about as usual, with Jason looking at his watch and exclaiming that he had to leave just when it was time to do the dishes.

But Gran’s mind was still running on vampires, I found out. She came into my room later, when I was putting on my makeup to go to work.

“How old you reckon the vampire is, the one you met?”

“I have no idea, Gran.” I was putting on my mascara, looking wide-eyed and trying to hold still so I wouldn’t poke myself in the eye, so my voice came out funny, as if I was trying out for a horror movie.

“Do you suppose . . . he might remember the War?”

I didn’t need to ask which war. After all, Gran was a charter member of the Descendants of the Glorious Dead.

“Could be,” I said, turning my face from side to side to make sure my blush was even.

“You think he might come to talk to us about it? We could have a special meeting.”

“At night,” I reminded her.

“Oh. Yes, it’d have to be.”

Both the book and the show take pains to push Grandma Stackhouse as this charming and harmless history aficionado who just wants to meet our mysterious vampire. However, I don’t think there’s anything that charming about an old woman that glorifies the antebellum south to the point where she calls dead Confederates “the Glorious Dead”.

And again, The Southern Vampire Mysteries and the True Blood television series are both incredibly white. These are pieces of urban fantasy media where the book kills off its one black character of any note by the second book and the television series introduces characters of color that are frequently killed off or objectified (or both).

One recurring problem in Urban Fantasy series is the way that, because of how allegories about oppression play out, oft-white vampires and werewolves are centered in stories where the humanity of people of color – especially Black people – is never given much of a thought.

Later in the book, Sookie and her grandmother have Bill over for lemonade and a chat about history and of course, the question of slavery comes up with the Stackhouses’ ancestors:

Of course, Gran was in genealogical hog heaven. She wanted to know all about Jonas, her husband’s great-great-great-great-grandfather.

“Did he own slaves?” she asked.

“Ma’am, if I remember correctly, he had a house slave and a yard slave. The house slave was a woman of middle age and the yard slave a very big young man, very strong, named Minas. But the Stackhouses mostly worked their own fields, as did my folks.”

In the television show, when Bill is asked about his past by the Stackhouses and Tara prior to meeting Descendants of the Glorious Dead – who will spend hours asking him questions in order to get a first-hand look at life before the War (of Northern Aggression, they call it) – he’s also asked about whether or not he and his family owned slaves. Here’s how the dialogue goes, combining the text about the Stackhouses from the novel with original-to-the-show dialogue in order to form backstory for Bill’s family:

Tara Thornton: Did you own slaves?

Bill Compton: I did not, but my father did. A house slave, a middle-aged woman whose name I cannot recall, and And a yard slave. A young, strong man named Minus.

Gran: This is just the sort of thing my club will be so interested in hearing about.

Tara: [narrowing her eyes] About slaves?

Gran: [with a nervous laugh] Well, about anything having to do with that time.

That last bit is said as a bit of an amusing afterthought to Tara that ends with Sookie giving Tara the evil eye.

Remember, Gran is supposed to be the epitome of charming Southern womanhood and she’s just the cutest old woman ever.

However, I have a bone to pick with the way that a) we’re supposed to be distancing Bill from the rest of the Comptons because his dad owned slaves but he didn’t… (except, nothing about the character indicates what kind of relationship he had with them and also, as a vampire he’s complicit in human slavery so…) and b) in the television show the character Tara (played by Black actress Rutina Wesley) is who asks him about owning slaves and whose question is treated as an imposition by the white people around her.

Mind you, that this is a guy from the tail end of the nineteenth century.

If Tara didn’t try and find out if he believed she was automatically lesser than him based on her blackness, I would’ve been worried that the show had even less of an idea on how to write black women than I thought they did before. But Tara asks the hard question, the one that any Black person in her position living in the South would ask of a vampire of that age, and in response, gets Bill talking about the slaves his family owned in a way that smacks of deflection.

I want to come back to The Cutting Season. Despite its contemporary settings, the novel is directly related to the plight of enslaved Africans through their descendants.

You have a majority of scenes set in the public and private spaces of a plantation turned historical park that butts up against a sugar cane field worked by mistreated Latinx migrant workers. One of the cabins where the plantation’s owners used to force their slaves to live is a home to a young woman brutally murdered at the start of the book and the memory of the main character Caren’s ancestors – the slave Jason and Caren’s mother who served as the cook for the estate for years – serve as ghosts of a sort.

One of the things about The Cutting Season that inspired this installment of Urban Fantasy 101 was the way that the novel balances the darkness of Southern history with the prideful and proud people that make the area their home and have for generations. Again, at no point is the reader being asked to gloss or skim over the realities of slavery or the way that it continues to affect Black people to this day.

The history of the antebellum South is alive but it’s not distilled down to quick, world or character building quips that manage to turn centuries of oppression into an easily ignored and touristy-fun fact.

In the end, that’s what I want from Urban Fantasy writers: I want them to acknowledge that when they’re writing in the South, that they’re writing in a space that has historically been unkind to real people. Using bigoted Southern stereotypes when you need to have vampires or werewolves hunted for who they are makes sense at first, but when you don’t – or can’t – grasp the ways that this same bigotry wasn’t always turned towards supernatural subjects?

We’ve got ourselves a problem.

More than that, you as an author have a problem because you’re not doing your job. You’re not doing a very good job of portraying the full world that your characters live in.

Don’t stop with shallow world building. As a writer, you need to do better than giving audiences a world where white vampires that are complicit in human slavery or where bigots get a pass because of what they are.

Narratives about characters of color in the South – especially Black characters – shouldn’t fall under the wayside in favor of reinforcing an ideal Southern life where, for all intents and purposes, everyone stays longing for the glorious antebellum days.

Well… everyone except for these Black characters and Black readers.

Advertisements Share this: