A hundred years after his birth, in 1869, almost every major city around the world celebrated the man who, at his peak, was the most famous man alive: Alexander von Humboldt. There were fireworks, street parades, speeches and festivities. He wasn’t a soldier, or a politician or an artist. The world was celebrating the anniversary of a scientist…one who pretty much invented the way we now consider nature and our place in the world.

In his time, he was probably the most famous scientist alive. People would queue for days to hear his lectures. If ever there was a rock star scientist celebrity, it was him.

Now, he’s hardly remembered.

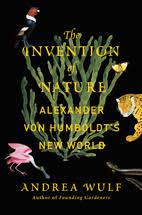

Andrea Wulf’s fascinating biography, “The Invention of Nature. The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt. The Lost Hero of Science” seeks to right that wrong. It’s a page-turning adventure story that’s as much about Humboldt as it is about those other (Humboldt-inspired) naturalists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all of whom she shows, helped to ‘create’ our understanding of our world.

The book takes us from the wet, crocodile-infested lagoons of the Amazon to the barren steppes of Mongolia to the salons of Goethe, Thomas Jefferson and the court of Napoleon.

This is Wulf’s thoroughly engaging reintroduction of this forgotten genius.

And what a genius!

Humboldt was born to a wealthy Prussian family (though he blew all his money on multiple, extended explorations in Latin America and Russia) His dramatic breakthrough was his recognition of the interconnectedness of nature, or the cosmos, as he called it (having decided that “cosmos” from the Greek, meaning “beauty” and “order”, was a more appropriate term than his initial idea: Gaia).

To understand the significance of Humboldt we need to consider the state of the science…the study of flora and fauna of the time. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, that time of African and Indian colonialism and scientific exploration, species were all studied in distinct silos. Naturalists either specialized in the study of the flora, the fauna, the weather patterns etc. Masses of knowledge was being gathered and recorded by the great naturalists such as Joseph Banks; but no one had the insight to figure out (or even question for that matter) how these elements were linked or influenced each other.

The studies were so geographically silo-ed that the similarities of one species in, say India was never collated with similar species in, say, Chile. And no one bothered to question the effects of man (through farming or manufacturing) on the environment. The idea of species’ co-existence and co-dependency, in what we now recognize as an ecosystem, simply did not exist.

They observed the butterflies…but the butterfly effect eluded them.

(It wasn’t until a few years after his death that another Humboldt-inspired naturalist, the German Ernst Haeckel – whose sumptuous drawings of sea creatures such as jellyfishes helped shape the stylistic language of Art Nouveau- described his (Humboldt’s) work as the “science of the relationship of an organism with its environment”.

It was he, in describing Humboldt’s contribution, that coined this term to describe it: ‘ecology’)

Humboldt shattered the segregated approach of his peers. Nature was no mechanistic clock (as Descartes had suggested); it was a living organism. Wound one part and all parts suffered. He proved for instance how the destruction of trees in one area affected the water levels in another. In Venezuela, he complained that the first colonists had “imprudently destroyed the forest” and warned against human initiated climate meddling.

He was our first ever eco-warrior. “Everything,” he said “is interaction and reciprocal” with man just another part of the whole.

This was major: authorities from Aristotle to Descartes to Montesquieu to the Bible had always insisted that nature was there merely to serve man. Humboldt begged to disagree. He offered the opposite and radical argument that unless man fully understood nature’s laws and his place in it, the consequences would be catastrophic.

It was his polymath intelligence (he studied finance and economics as well as geology; conducted experiments, often on himself, on the nature of magnetism and electricity; and, of course became the world’s pre-eminent botanist), his legendary memory (which allowed him to compare observations he made all over the world several decades or thousands of miles apart) and his relentless curiosity combined with an explorer’s risk-indifferent fearlessness, that empowered his radical insights.

Moreover, he stood out from the legions of enlightenment scientists and botanists not only in the way he was able to show the (previously unconsidered) interconnectedness of the world, but in a style of presentation that eschewed the dry, empiricist presentation of fact and data. Humboldt, following a lead set by Immanuel Kant, allowed his subjective – Romantic – sensibility to frame and evoke the brave new world he was discovering. His legions of fans and followers came not simply from his startling discoveries, but from the exciting, captivating way he presented these discoveries. He introduced poetry and lyricism to science. He made the study of nature both enjoyable and accessible. As the author notes, “everybody learned from him, farmers and craftsmen, schoolboys and teachers…”

It all began really with his journey to Latin America.

Europe at the time was aflame. The French Revolution had led to France’s declaration of war against pretty much everyone else. It was around this time, in Paris, where he was trying to get funding, that he met Aime Bompland, a like-minded soul with whom he would share some of his greatest ‘adventures’ (and, as he did with several other like-minded young scientists over the years, probably much more). But funding came, not from the French, but the Spanish. For the first time, the Spanish granted permission to a foreigner to roam and explore the colonies in South America. And so, two years after his mother’s death, equipped with the latest instruments, from telescopes to microscopes to barometers to compasses (forty-two instruments in all, including a cyanometer, to measure the blueness of the sky), he set sail from La Coruña in Spain on the frigate Pizarro on a journey that would take him five years.

After forty-one days at sea, they made landfall at Cumana in New Andalusia, or Venezuela. The journey would take him as far south as Lima, via Cartagena and Bogota and as far north as Philadelphia via Mexico City and Havana. His intent was to observe, measure and figure out everything he could.

This was no mere expedition to collect plants. To him, it was a collection, comparison and analysis of ideas. It was “the impression of the whole” that captivated his mind more than anything. His journey saw him wrestling with the proto-Darwinian ideas of species’ evolution even as he mapped rivers, measured the heights of mountain ranges and the electricity of electric eels, the effects of barometric pressures and teetering at the edge of volcanoes recorded everything he could (Were all volcanoes linked together? Were they responsible for the shape of the earth? he wondered) And he compared everything he saw with what he’d previously observed in Europe. This was the web where everything was linked together. If only he could figure out the nature of the links.

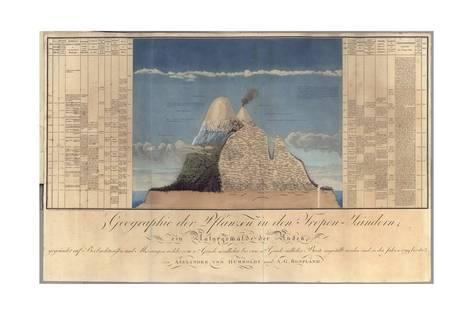

He figured it out and illustrated his vision of the interconnected of everything with a sketch he called the Naturgemalde. This showed different zones of plants, along with details of how they were linked to changes in altitude, temperature etc…how it all fitted together. To the naturalist community around the world (not to mention his own interconnected links of friends, scholars, artists and the legion of contemporary thinkers he influenced: Goethe, Thomas Jefferson, Simon Bolivar, the English naturalist Joseph Banks, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Thoreau, Whitman, Poe, Jules Verne, Emerson, Darwin, the German philosopher Freidrich Schelling etc) the sketch was a seismic shock. Suddenly it was as if curtains of ignorance had been lifted; the portal to a new way of regarding the world had been opened.

Like his prose style, the simplicity of the scientific information depicted was unprecedented. This illustration was to be the centerpiece of his first major work: “Voyage to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent”. Thirty-three volumes would follow. Some, such as his magisterial, encyclopedic five volume “Cosmos” – described by Wulf as “a portrait of nature as a whole [including the constellations] in which each detail was like a thread in the tapestry of the natural world” – were hands down bestsellers.

In his journeys in Latin America, he also saw first hand, and grew to despise, both slavery and colonialism (a sentiment that attracted a young Simon Bolivar to him when they met in Paris). Indeed, he noted that Spanish colonialism, through its emphasis on a mono-culture, was responsible for the devastation of the environment. And though he championed the struggles for independence and freedom of the new American nation, he still railed against the iniquities of their slave holding laws. He was morewove, one of the few early explorers who did not denigrate the ‘sophistication’ of the indigenous peoples he encountered.

After his return from Latin America, he longed to light out for new horizons. And the horizon he most set his heart on was India. He never made it. Despite pulling every string he could manage, the British (in the guise of the East Indian Company) wary of his anti-colonial sentiments, frustrated him at every turn and refused to grant him the necessary travel permissions.

Living between Paris, London and Berlin, this was a deeply frustrating time for Humboldt. He took out his frustration by inventing “isotherms”, the lines that connect different geographical points around the globe that are experiencing the same temperatures. Humboldt’s graphic visualization of data was once more, “as innovative as it was simple” writes Wulf.

Finally escape came in the form of an all expenses-paid expedition to explore and report back on the ‘wilds’ of Russia (funded by tsar Nicolas I, who wanted to learn of the minerals available and potential mining opportunities). Unlike the skeleton few he took with him to Latin America, the Russia expedition was made up of a vast retinue. There was a mineralogist, a naturalist, a zoologist, a cook, even a convoy of Cossacks, along with three carriages of instruments. It was Humboldt’s observations of how various minerals clustered together in Latin America that accurately helped him predict the presence of diamonds. People thought he was some sort of magician. The journey took him to the edges of the Russia empire, where he met Mongolians. He celebrated his sixtieth birthday with the nomadic Kyrgyz and their local apothecary, a man who history would remember as the grandfather of Lenin.

It was on this expedition, as he noted in the publications that recorded his discoveries, that humans were, increasingly adversely, affecting the environment. He named deforestation, ruthless irrigation and the excesses of “steam and gas produced in the industrial centres” as the main culprits for the worsening environmental problems he foresaw.

When he died at 89, his funeral attracted some 10,000 mourners.

The book is called “The Invention of Nature”. And though it is by and large a biography of Humboldt, it often segues into many other (Humboldt inspired) major naturalists whose work built on Humboldt’s. Proto-environmentalist, James Madison also warned against deforestation (the result of intensive tobacco farming) and called upon his fellow citizens to protect the environment. Then as now, capitalism won out.

Simon Bolivar enshrined Humboldt’s ideas into law when he issued the decree mandating Bolivia’s government to plant one million trees.

But one of the more prescient of these early earth lovers was the American George Perkins Marsh (George who?). Marsh spoke twenty languages, was Lincoln’s ambassador to Italy and helped establish the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. His work also sought to prove the (often disastrous) influence of man on the natural world. “All Nature is linked together by invisible bonds” he wrote echoing Humboldt. His major work, “Man and Nature” (which he’d originally sought to call “Man the Disturber of Nature’s Harmonies”) offered the bleak conclusion that – referring to the insensitive overgrazing and unrestrained use of water in the agricultural practices of the US and Europe – if nothing changed the planet would be reduced to a condition of “shattered surface, of climatic excess…perhaps even extinction of the [human] species”

Who knew: one hundred and fifty years ago, these brilliant scientists were already worrying about the eco-system in which all flora and fauna interconnect; worrying about man’s increasingly destructive role in this interconnection. Then as now, knowledge could only be acted on so long as profit was not being compromised.

No wonder the world has forgotten about Humboldt. Not to mention Marsh, Thoreau, Madison and their likes…A collective amnesia spread initially by post-war nationalism (After the first world war, the world willed itself to forget ‘all’ Germans) along with Big Oil and its paid for pseudo scientists and now spearheaded by a president who regards all this climate change stuff as a just a ploy developed by the Chinese.

There’s another engaging book that seems to ‘complete the circle’ by one Jason W. Moore. The title tells it all: “Anthropocene or Capitalocene. Nature, History and the Crisis of Capitalism”

Advertisements Share this: