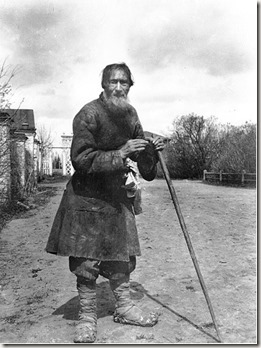

You can walk through Red Square, down all the grand avenues of Moscow, through its empty, gray backstreets and you will never find it. You can do the same in St. Petersburg: walk down Nevsky Prospect, past Kazan Cathedral all the way to the Winter Palace. Or follow the winding paths Raskolnikov took through the back streets, but you won’t find it there either. You can go to Nizhny Novgorod or Ulyanovsk or Samara or Volgograd or further south and east and do the same thing: walk down the main avenues, through the grandest squares or the quietest backstreets and you won’t find it there either…

So, what is it? It is a memorial to the Russian soldiers of World War I. You can find plenty of monuments to Russia’s involvement in World War II, of course. And you will find a number of monuments to plenty other wars Russia got involved in: the Napoleonic wars are easy to find, and other smaller conflicts have monuments here and there. But despite the size of World War I and the sacrifice of the average Russian solider (over two million of them died), you’ll find little to suggest it ever happened. Sometimes, walking around Russia—which usually does a good job of commemorating history—it feels as if it never happened.

But that’s not exactly true, is it? And I’m not being quite straightforward either. Because one day, I did find a monument to the Russian soldiers of World War I. On a gray, wet, cold day I came across a small, well-kept monument tucked away on a small side street. It was a little smaller than the height of a man and it was in memory of the high sacrifice so many of those men made. I was struck that it was the first time I had EVER seen a monument, of any size, to the Russian soldiers of World War I. I had a solemn moment next to the monument and was on my way.

So, why was this war almost forgotten there? How did it happen? Well, it’s easy. The Russian Revolution. The Great War was viewed as a struggle between capitalistic powers by the victors of the Russian Revolutions, the Bolsheviks. As such, it was hardly worth commemorating or celebrating. And so, a hundred years after Russian famously “left the war,” there is hardly any trace of the conflict left. Which leads me to this week’s big question…

Was the Revolution a Break with the Past or a Continuation of It?

I have come to believe that the Russian Revolution was a continuation of older patterns in Russian culture and history…It was not, and should not, be viewed as a millennial disruption with the past. Here’s why I think this way:

Geography

Russia is vast, but mostly defenseless. OK, that’s a gross oversimplification. But think about it: It’s mostly a vast open plain or forest. There are not natural barriers to an invasion on pretty much any side, except the north. Sure, there are the Urals, but they’re pretty small. They certainly were not obstacles to the Mongols who invaded on horseback. Of course, there is the one Killer natural obstacle: the winters. And yes, General January and General February have done amazing jobs of stopping invading armies in their tracks. But overall Russia is a vast, thinly-populated resource-heavy prize waiting to be taken. And the Russians themselves are keenly aware of this. It’s written into their history.

And one more thing on geography which many of America’s Founding Fathers noted in The Federalist Papers: democracy seemed to develop and flourish first in islands or isolated environments. That usually meant Britain or Venice in their thinking. But there are other examples like Switzerland that come to mind. This is not a rock solid theory, but if you don’t think this applies today, look at a map of East Asia and consider what kind of political system the islands have (Japan, Philippines, Taiwan, and we’ll throw in South Korea) and what kind of political system mainland nations have (China, Vietnam, North Korea, etc.). Coincidence or the influence of geography? I’ll let you decide.

History—In Three Easy Pieces

So, building on geography…What sort of history did Russia have as a result? Was it calm and bloodless? Or a bit more turbulent? I think you know. But let’s explore some of the big themes.

1. Collapse I—From Without: The Mongol Invasion

It’s hard to overemphasize the effect of the Mongol Invasion on the Russian psyche to this day. I remember seeing children’s cartoons (cartoons!) which replayed (less violently) the story of the debacle of the Mongol invasion of Russia. It went something like this: a Russian village is quietly minding its own business when the Mongols appear on the horizon, blotting out the sun with their arrows. They swoop in and devastate the land and almost nothing is left. And this was for the kids!

So much for the historical accuracy of cartoons. But the Mongol invasion was astonishingly successful AND long-lived. (By the way, they invaded Russia in the WINTER, so note to future would-be conquerors!). They ruled the heartland of Russia for about 200 years, leaving a major impact on many institutions—for bad and good. They kept hold of various parts of Russia for some time: Catherine the Great finally swept away the last of the legacy Mongol states in the late 1700s!

The bottom line: Russia would make it a priority from the 1200s on that it would always be prepared for a major foreign invasion at any time—and would have an army to make good on it.

2. Collapse II—From Within: The Time of Troubles

Problem is…It’s not always “them foreigners” who bring down a country. Sometimes, it’s the citizens themselves. (Imagine that!) And sometimes they find foreigners to help them.

In the early 1600s Russia was exhausted after wars and unrest unleashed at the end of Ivan the Terrible’s reign. A famine and other catastrophes followed, further weakening the state and the economy. Soon, the entire country descended into full-blown anarchy and chaos: the Time of Troubles. It was a turn of events that its neighbors—especially Poland—could not pass up, and they duly invaded. Usurpers and con artists took over the position of tsar. Eventually, a coalition of Russian citizens rose up, united and kicked out the invaders and placed the first of the Romanovs on the throne.

But again, the psychic damage was done. Few countries have experienced full-blown anarchy on such a scale. This too, was something that must NEVER be repeated. But the threat had come (mostly) from within. So, perhaps the citizens should be watched just as vigilantly as the foreigners…

3. A Messianic Nation

And historically, there’s one more thing. As many have noted, for a very long time, Russia has thought of itself as a special nation, a place apart. Ivan the Terrible has been credited with introducing or emphasizing this concept. It was Ivan who named himself tsar (The Russian word for Caesar) to emphasize the country’s link to the Byzantine empire. Accordingly, Russia at times viewed itself as the 3rd Rome, taking on the mantle of all that numinous history.

You can also find this concept that Russia will redeem the world in art, literature and music. Dostoyevsky, especially, was a big proponent of this idea, but he wasn’t alone. There was a feeling among the intelligentsia and many others in the aristocracy and working classes that Russia had a special mission, a special role to play in the destiny of all mankind.

This feeling can be a good and powerful thing, but in retrospect it can also be twisted to serve other ends that are not as wholesome.

…And a Theory of History and Power

So where does all this leave us? A fear of foreign invasion and of domestic anarchy? And a messianic vision?

One of the first historians to attempt a holistic vision of Russian history, and still one of the best, came to a startling conclusion. His name was Nicolai Karamazin.

He decided that the system Russia really needed was the one it already had: autocracy. In his famous History of the Russian State, he argued that history and geography were inescapable realities. Russia was no small, insular mountainous country or remote island. It was a vast realm in the heart of Eurasia. And it had a history of foreign invasions coming thick and fast and the ever-present threat of rebellion and anarchy from within. It was naturally suited to autocracy. And, in fact, autocracy had saved Russia. Without autocracy and the tsar, Russia would succumb to its natural centrifugal forces—flying off into a thousands different ethnicities, religions and groups all at one another’s throats—just like during the Time of Troubles. Only the tsar could save and preserve the Russian state. Needless to say, the tsar liked his book! Over time this concept morphed into the tsarist formula of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality”—a new formula known as Official Nationality under Nicolas I.

Interestingly, Karamazin was ethnically a Tatar, one of the Mongol groups which had accompanied (and suffered from) Genghis khan and his general and sons’ original conquests. Perhaps he believed only a khan could master the steppe. Oops! I mean “only a tsar could rule Russia.”

The Dynamo of Russian History: Lost Wars Result in Reform

Karamazin’s theory fits pretty well and it’s a neat, tidy analysis. I think Karamazin had a point, but was not entirely right. Geography and history, though compelling, are not fate. Humans can choose their destiny, rightly or wrongly. If Russia had not entered World War I and stayed aloof, czarism might have prevailed. Or Russian could have transitioned—probably still bloodily and chaotically—into a constitutional monarchy (consider modern Spanish history)—or even become a democracy at some point. But the fact is, it didn’t. Russia followed an older pattern. In 1914, Russia like most countries, it optimistically entered the war. But the war became a deadlocked bloodbath. Gross incompetence led to losses and the economy suffered as inflation soared. The tsar fell and the Bolsheviks, taking a bold risk and with plenty of help from Germany—pulled off a coup and seized power in the name of the people and began the world’s first Communist state. But was it such a break with history as the Bolsheviks claimed?

I believe this pattern fits with Karamazin, but I will add one more thing: The Dynamo of Russian History. It’s essentially this: every major reform or revolution in Russia has come about as a result of military defeat. So, let’s take a look:

| Year | Military Defeat | Reform/Revolution |

| 1200s-1400s | Mongol Invasion | Crushing of Novgorod, Pskov Republics. Primacy of Grand Prince of Moscow. |

| 1598-1613 | The Time of Troubles/Polish invasion | Foundation of Romanov dynasty |

| 1700 | Defeat at Battle of Narva | Western reforms of Peter |

| 1856 | Defeat in Crimean War | Emancipation of the serfs |

| 1905 | Defeat in Russo-Japanese War | 1905 Russia revolution, foundation of the Duma |

| 1917 | Inept participation in World War I | Bolshevik Revolution |

| 1989-1991 | Defeat in Afghanistan | Collapse of the USSR, free market “shock therapy” reforms under Yeltsin |

| ??? | ??? | ??? |

I guess you could say, the Russians pride themselves on being good in a fight. (And they are!) But when they lose, and especially when they lose big, they cast about for someone to blame and it’s usually the current leadership.

Of course, this is a gross oversimplification of complex history. And it fits some data points nicely and others not so much. The best matchup is the Crimean War and the emancipation of the serfs. In 1856 it became clear that Russia could no longer militarily, economically and technologically compete with the other Great Powers. Something was holding back the country and needed to change. One glaring difference was that serfdom was still alive and well in Russia and it became the main culprit. So, a new czar came to the throne and freed the serfs almost overnight. Others events don’t fit as well. For example, Russia won the Napoleonic War, but still faced a massive revolution known as the Decembrists Uprising a few years later. So this idea doesn’t always fit.

It may also simple be a trait of human (not just Russian) nature: during times of war we’re more liable to be outward thinking. When peace is declared and the armies come home, we start thinking about the people closer to us we and the problems at home that have been festering while the troops were abroad. Suddenly, all that outward facing energy is facing inward and upheaval can result.

And also importantly: I don’t want this to minimize the bloody badness of the Russian Revolution and subsequent related atrocities and—let’s be honest—crimes. The Russian Revolution wasn’t simply a “reform” it was also an elemental upheaval that destroyed millions of lives and still has a negative effect on the country today.

What Might this Mean for Russia’s Future?

So, what might this mean for the future? This is where the fun comes in. And someday, we’ll see if this model has any predictive power. The chief thing is to watch and wait and see if Russia is involved in any wars and starts losing them. Recently, there were the two Chechen wars which Russia was able to extricate itself from, if not win. Then, there were a few wars with Russia’s neighbors, most notably its intervention in the Ukraine in which it won back the Crimea—fair to say not a loss either. The Russian intervention in Syria is perhaps the most notable one they are involved in currently. But, so far, the war seems to be breaking Russia’s way. So, it seems we’ll have to wait a bit more to see if Russia starts losing a war—and it might mean tumult is on the way.

Of course, economic dislocation, resulting in shelves in the capitals of Moscow and St. Pete becoming empty so that the middle class is forced to eat just bread, butter and potatoes might also result in upheaval. It certainly did as recently at the late 80s. Putin appears to be pretty cognizant of both military and economic threats, so it might be quite some time before we see these two strains intertwining and causing chaos again. Bet he (or his advisors) have read their Karamazin!

Bottom Line

Bottom line: The Russian revolution and Bolshevik coup of 1917 should not be seen as total break in Russian history. Revolution and anarchy certainly are nothing new in Russian history. Nor is autocracy. (Maybe they are different sides of the same coin?) In fact, you could argue that the autocracy quickly reasserted itself with the advent of Stalinism, fifteen years after the start of the Revolution (around 1932) as a new, more powerful tsar solidified his grasp on the Kremlin. (Incidentally, that’s almost as long as the Time of Troubles lasted.) And now, though the economic model of the USSR has been smashed, the new Russian leadership has discovered a new capitalist model in which they retain control of “the commanding heights” of the economy while allowing for some capitalist characteristics. The central kernel of Russian autocracy through all sorts of pressures (wars, anarchy, economic collapse) has evolved, adapted and survived. Karamazin would be amazed. But he wouldn’t be surprised.

Phew! That was a long one! Next time, we’ll get back to our regularly scheduled programming and return to talking about writing. Russia has been an obsession of mine and I just couldn’t let the 100th anniversary go by without doing something.

See you next time!

Darius

PS…And just as I was about to post, this article came up on whether the U.S. has forgotten about its role in World War I! It’s true that it’s not very easy to find WWI monuments in America, either.

Advertisements Share this: