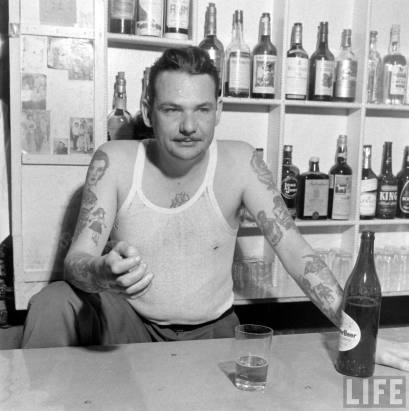

In May 1949 Life‘s Shanghai Bureau photographer, Jack Birns, accompanied by its reporter Roy Rowan did the rounds of those bars and cabarets in the city that catered in the main for foreign sailors. You can find most of the photographs, which were not used at the time, in the Google Images Life Archive (search for ‘China, Last Days Of Shanghai‘, then browse). With a little patience you’ll find sets of photographs of bars and their owners, and the Chinese and Russian hostesses who entertained the patrons. You will not find many of the latter, for the Communist armies were moving on the city, so the bars are eerily empty. For that reason, I used one of these in Out of China as well as another taken in a Macao casino: two Chinas (of many). One staged set of the Shanghai photographs follows two seamen on shore leave from the gates of the wharf as they negotiate with cycle rickshaws, and traverse the Diamond and Lear Bars. They are the only customers.

Daisy Gao Kia Kin and Frank Yenalevicz, New Ritz Bar, Shanghai, May 1949 by Jack Birns © Time Inc.

The New Ritz Bar, whose owners, Daisy and Frank Yenalevicz, posed for the portrait above in May 1949, looked a higher class of establishment than some they visited, even though it was part of the ‘Blood Alley’ strip on Rue Chu Pao San in the former French Concession close by the river-front Bund and across Avenue Edward VII from the former International Settlement. It is the only one which had Chinese customers as well, here shown playing dice.

New Ritz Bar, May 1949, by Jack Birns, © Time Inc.

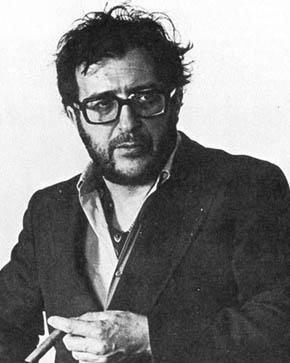

Robert ‘Bo’ Brown, Diamond Bar, Shanghai, by Jack Birns, 1949 © Time Inc.

The details which accompany these photographs might give the name of the owner, Yenalevicz, or Jim Lear (Lear Bar) or Bobby ‘Bo’ Brown, owner of the Diamond Bar. The interest of Life‘s editors might have stretched to the Americans who ran or patronised these forlorn establishments, so Rowan and Birns provided some notes on them, and Birns took their portraits. Brown, we are told, for example, was a Chicago-born former Merchant Seaman, who had bought his business in 1946. You can find the odd reference to these men in the press: Lear being fined in 1948 for accepting US dollars as payment (which was illegal); Yanelevicz’s bar being declared ‘Out of Bounds’ by the US Navy that same year, and Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury editor Randall Gould ripping the sign down, declaring that extraterritoriality was over, and the US Navy had no right to fix a sign to anybody’s business in Shanghai.

It was Daisy who piqued my interest, however, or rather the woman I now know to be Daisy, or to be accurate, know to be 高桂金, Gao Guijin (or Gao Kwia Kin in the transliteration used in various documents). This was because she looks very much Yenalevicz’s equal. And well she might, for she owned, she said, half the business. She could, and did, prove it.

Frank Yenalevicz, native of Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania, died in September 1949 in Shanghai’s Country Hospital of heart failure. He was fifty years old. Four months later Daisy requested assistance from the US Consulate General to help her wind up his affairs. This letter was clearly written by a native-speaker of English, but there is no clue as to who was helping her at this point. Daisy had met Frank, she wrote, in 1923, then followed him on his US Navy postings around the Pacific until he left the service in 1933 after which they settled in Shanghai. There they ran their business, Daisy attending to the restaurant, and Frank to the bar. The New Ritz was taken over sometime after summer 1939. She ran it on her own during the Pacific War (when, after internment at Haiphong Road Camp in November 1942, Frank secured passage to the US on an exchange ship in September 1943), and accumulated substantial savings that they held in US dollars. Blood Alley’s business did not lag during the Japanese occupation. To avoid currency controls introduced by the Chinese government in 1948, Frank deposited their capital in a New York bank account in his name. By January 1950 the business itself was essentially worthless. Even the properties they leased — including ‘a comfortable apartment in a modern building’ where they had ‘lived respectably as man and wife’ (though they had never married) — were now valueless. She still ran the business, she said, but ‘Conditions here are now so unfavorable’ — after eight months of Communist control of the city — that she was by then in great need of the money held overseas.

Daisy’s vulnerability was also made evident when she offered a payment from the estate, without prejudice, to each of Yenalevicz’s siblings. She had never had any contact with the family, she wrote, but US consular officials with experience of Shanghai would be able to vouch for her story, for Frank would have been known to them (which was probably true, not least because of the May 1948 contretemps). Nothing seems to have happened, however, as events — the closure of the US consulate general, the onset of the Korean War and the US-led trade embargo against China — conspired to obstruct Daisy’s attempts at restitution. Meanwhile the business stumbled on, although perhaps dice no longer rolled across the tablecloths. A September 1952 report in John W. Powell’s China Monthly Review recorded that the bar was still serving ‘American style lunches and dinners’, including his ‘next T-Bone steak’ (Powell’s pro-PRC magazine aimed to rebut US claims about food shortages). Still, beef or no beef, Daisy was anxious to regain her money. In May 1953 she tried again through a set of New York lawyers but there is no record in the file of any success.

For now, Daisy’s tale remains suspended here, and the woman herself is frozen in the record, snapped behind the bar at the New Ritz by Jack Birns, and lodged in this US State Department file, precariously, but comfortably, living in her eighth-floor rooms in the Yates Apartments on Bubbling Well Road. But the dossier on Frank’s estate provides a glimpse nonetheless of some of the more mundane realities behind the much-mythologised ‘Blood Alley’. From time to time the Birns photographs are rediscovered and re-circulated online as showing foreign decadence in the shadow in the Communist victory. Well, this was, all in all, the brief given to Birns and Rowan when they were sent to Shanghai.

But in catching Daisy, Birns also caught another way of viewing the world that was about to be taken over, one that I explore in greater depth in Out of China: the messy lived experience of treaty port China. Here were middle-aged Frank and Gao Guijin, who had dodged the war and the inflationary crisis of the late 1940s through fair means and rather more pragmatic ones, keeping their businesses open and their customers satisfied. Under one regime their properties will best have been registered in Frank’s name, and will have been protected that way by his American extraterritorial rights, which lasted formally until 1943. But during the Japanese occupation and then in the post-war years, it was plainly easier to run them as Daisy’s. To mangle a famous saying of Deng Xiaoping’s: it did not matter to them if the New Ritz cat was American or Chinese, as long as it attracted the mice.

So Daisy and Frank were, it seems, a comfortable team, adroitly working their niche in the politically mis-shaped world of treaty port China. They lived well, and earned well, although the living was sometimes not without danger. The New Ritz’s previous owner, Albert Fletcher Wilson, had been killed in July 1939 just outside the bar, shot by pro-Japanese terrorists during a series of attacks on government newspapers. But the greatest challenge Daisy faced as its owner, however, proved to be her husband’s death and the entangled legal consequences of their never having married, as well as their strategies for survival through the Pacific war and China’s post-war crisis. The wrenching reconfiguration of the Cold War finally threw up challenges that even the most adept found difficult to manage. Daisy’s attempts to regain their savings may also have been prompted by the tightening policies of the new city authorities in the early 1950s, and the scrutiny of the business and its assets that this would have entailed. Things might have got much more difficult for her in Shanghai thereafter as a small business owner with long-term American connections.

This Sino-American partnership was trapped by history. And while the ‘Blood Alley’ approach to night-time Shanghai’s foreign-flavoured history has its truths, even these are better understood if we look more closely behind the lurid headlines to the real world of Gao Guijin, who opened up the restaurant every morning, and posed calmly next to Frank Yenalevicz for Jack Birns.

Sources: US National Archives Record Group 59; Box 1205, Case No. 293.111 Yenalevicz; China Monthly Review, 1 September 1952, pp. 296-300; South China Morning Post, 17 May 1948, p. 10.

Share this: