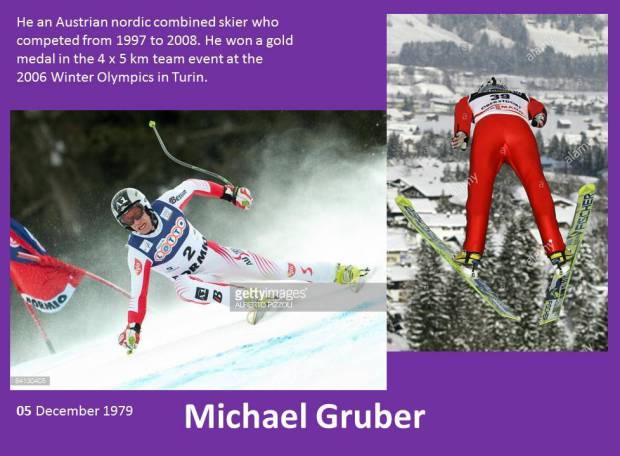

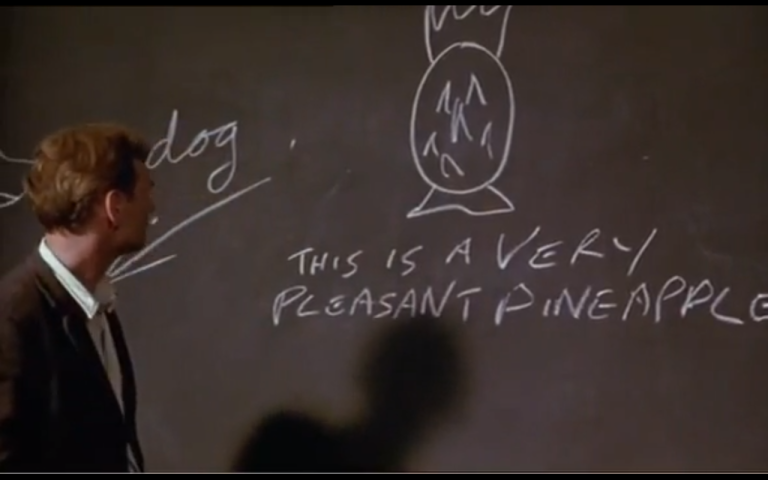

Karl Johnson as Ludwig Wittgenstein in Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein (1993)I don’t often write about my teaching work, largely because it takes an effort to stop thinking about my teaching work. Isabella Rossellini says “If I were a praying mantis …” and, even as I watch her dry-humping a life-sized cardboard mate, I’m thinking “Ooh! Second conditional”. That one went nowhere because as a teacher of beginners the second conditional is inappropriate for reasons more intrinsic than classroom awkwardness, but a night of insomnia, which reading about Ludwig Wittgenstein failed to end, produced “What does ‘water’ mean?” This seems both more profitable in my classroom and philosophically interesting. As I am rather proud of it, I publish it here for English teachers, who like myself wrestle with their students’ belief that a phone or even dictionary, will illuminate all that is in darkness, as well as those who teach and study how meaning is made and how language works more generally.

Karl Johnson as Ludwig Wittgenstein in Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein (1993)I don’t often write about my teaching work, largely because it takes an effort to stop thinking about my teaching work. Isabella Rossellini says “If I were a praying mantis …” and, even as I watch her dry-humping a life-sized cardboard mate, I’m thinking “Ooh! Second conditional”. That one went nowhere because as a teacher of beginners the second conditional is inappropriate for reasons more intrinsic than classroom awkwardness, but a night of insomnia, which reading about Ludwig Wittgenstein failed to end, produced “What does ‘water’ mean?” This seems both more profitable in my classroom and philosophically interesting. As I am rather proud of it, I publish it here for English teachers, who like myself wrestle with their students’ belief that a phone or even dictionary, will illuminate all that is in darkness, as well as those who teach and study how meaning is made and how language works more generally.

The exercise itself is self-explanatory – what do the emojis mean when they say “water”? – but Wittgenstein’s ideas are very complex. I leave it to others explain the differences between his view and Saussure’s structuralist approach to language, but they share an idea that meaning depends on context. So, while we all have a relatively clear idea of what water is, what “water” means is highly varied and depends who says “water”, as well as where, when, and how it is said.

For me, this underscores the difference between being, or ontology in which the exclamation “Water!” is without moral consequence, and meaning, or teleology in which it is a demand or a warning depending on whether it is said in the context of a fire the water might extinguish or of electricity where contact with water might cause a fire. Without context, the word is meaningless, even idiotic. Equally, the sentence “He threw water onto the fire” is meaningless until we know who throws water onto the fire, when this was done (before it catches or in the dead of night), where it is done (in a house or the Arctic), and why (to save lives, to conceal them from predators, or to stop others keeping warm).

As for the sentence, so for the water and action themselves, and until questions of who, when, where, and why are answered it is impossible to say if water and action are a help or a hinderance, good or bad.

Meaning is morality, and just as meaning is always constructed and construed, so, until we build for ourselves a moral edifice, the being of the thrower, the water and the fire, as well as the action of throwing the one on the other are all without moral consequence. Needless to say, any moral edifice is itself contingent on a set of metaphorical foundations and even if we formulate morals for a world as we would have it, we must live in the world as we find it. That is, there are no transcendent values. Life is generally agreed to be an absolute good until genocidal maniacs enter the fray. At this point the gambler and wiser philosophers alike take their bets off the table, some to trade in arms, some to buy diamonds, most to see how the chips fall.

More topical and less dramatic, is the Rentboy.com case. The US government called it “one of the largest sex work ventures ever prosecuted”. At sentencing in Brooklyn, the judge said: “The very act that was illegal; it did a lot of good.”

Here is a link to the exercise and here is a relevant, and very funny, film clip.

Advertisements Share this: