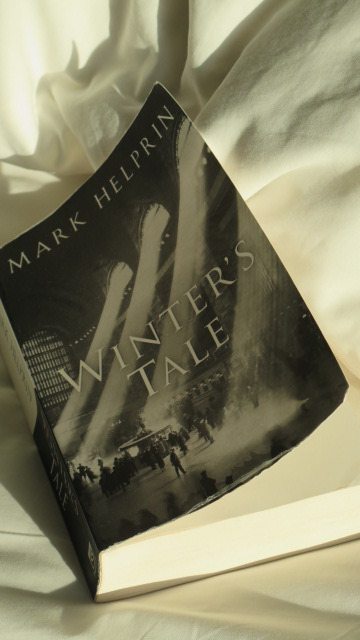

It’s appropriate, given Mark Helprin’s discursive, meandering narrative in Winter’s Tale, that I came to his book in an unexpected, roundabout way. Hearing The Waterboys’ song Beverly Penn for the first time on a CD of out-takes from the This Is The Sea album, I investigated (okay, Googled) what the title referred to and found the novel. Sure enough, the song’s writer Mike Scott had read the book ‘shortly before the album was made’. Oddly, the better-known Scott composition the book most reminded me of was The Whole Of The Moon. ‘Unicorns and cannonballs’ don’t appear in Helprin’s writing, although there is an important white horse. Glancing over the album sleevenotes, I see that Scott says he couldn’t have written the song without Helprin’s influence. So that would be it. ‘Every precious dream and vision underneath the stars’, indeed. Anyway, I digress: Beverly is a beautiful teenage consumptive in an arctic New York, at the end of the 19th century. She falls in love with an Irish burglar, Peter Lake, but dies soon after. As we move through the next century, things get weird. Helprin does not create a realistic world, but it is a truthful one. New York does, in my limited experience, feel exactly as he describes, especially ‘the overwhelming mass of its architecture, in which time crossed and mixed’. Early on in Winter’s Tale I was reduced to – no, I was compelled to do so – writing things down: plot things, character things, e.g. how could such and such only be a little girl after all this time, how can so-and-so even be still alive, and so on. Characters who should be in their nineties are only in their thirties. And don’t be afeard, you readers who like things tied up neatly – all is eventually revealed. Unusually, this does not dilute the effect. I’m not sure that discipline is Helprin’s strong point as a writer, but there’s nothing so very admirable about discipline. A film version, A New York Winter’s Tale, was released a few years ago, to general indifference. It is probably awful, but to even attempt to visualise this sprawling, demanding, quite brilliant novel counts as an act of minor heroism.

Advertisements Share this: