Directed By: Stephen Chbosky

Written By: Stephen Chbosky, Steve Conrad and Jack Thorne (based on the novel Wonder by R.J Palacio)

Starring: Jacob Tremblay, Julia Roberts, Owen Wilson, Izabela Vidovic, Mandy Patinkin

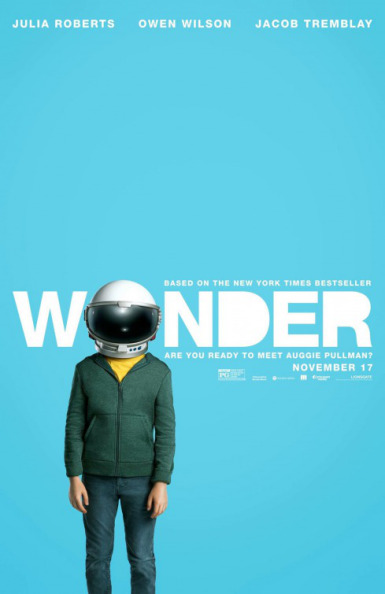

In Wonder, based upon the  best-selling novel by R.J Palacio, a ten year-old-Star Wars fanatic born with severe facial abnormalities, named Auggie Pullman, removes the toy space helmet he has long been using to shield his features from the outside world, leaves behind his mother’s home-schooling, and enters the public education domain for the first time. Auggie’s ears are fleshy bulbs, his chin is retracted, his cheeks are coated in scar tissue, he looks “different” to use his words— physical differences which land him at the centre of both hideous bullying (kids liken him to Freddie Krueger, and fear they’ll contract the plague merely by touching him), and, more powerfully, brimming affection. Many motivational speeches follow, many lessons too, many tears, many laughs, more tears still, an overt kindness-trumps-all thesis, and far too many standing ovations. It’s a sentimental minefield.

best-selling novel by R.J Palacio, a ten year-old-Star Wars fanatic born with severe facial abnormalities, named Auggie Pullman, removes the toy space helmet he has long been using to shield his features from the outside world, leaves behind his mother’s home-schooling, and enters the public education domain for the first time. Auggie’s ears are fleshy bulbs, his chin is retracted, his cheeks are coated in scar tissue, he looks “different” to use his words— physical differences which land him at the centre of both hideous bullying (kids liken him to Freddie Krueger, and fear they’ll contract the plague merely by touching him), and, more powerfully, brimming affection. Many motivational speeches follow, many lessons too, many tears, many laughs, more tears still, an overt kindness-trumps-all thesis, and far too many standing ovations. It’s a sentimental minefield.

The pitch for Wonder is enough to trigger even the mushiest movie goer’s alarm bells; the sort so apparently rife with mawkishness that one can hear the violins long before they’ve even bought their ticket. But Wonder somehow isn’t that sort of movie. Unsubtle? Yes. Unabashed tear-jerker? Absolutely. But never does Wonder take the easy route; never is it cheap. Rather, this is the rare Hollywood heart-string tugger defined by humanism and sensitivity, rather than exploitation and soppiness.

It’s an incredibly tight balancing act between sentiment and sincerity that’s negotiated by author-turned-filmmaker Stephen Chbosky (known best behind the camera for The Perks of Being a Wall Flower), finding anchorage not specifically in Auggie, but in the vast emotional ecosystem that he has both spawned and is enveloped by.

How tempting it might have been for Chbosky and cowriters Jack Thorne and Steve Conrad to milk Auggie’s struggles for easy affect, to mine the inherent heartache of that central theme and coast upon it. But these filmmakers are much too sophisticated for that, instead opting for empathy and perspective, widening their scope to examine the surrounding waters Auggie’s life has rippled and achieve a deeper human understanding.

Among those rippled waters are Mr and Mrs Pullman, Isabel and Nate (played by Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson respectively), the two weary yet endlessly devoted parents who forever fight to instil in Auggie pride. Julia Roberts may steal the show as the worn but gallant mother, flawed and occasionally feisty, but always teeming with maternal warmth, that trademark Roberts smile able as ever in igniting the screen with a romantic glow. By turn, Wilson offers appreciable bouts of levity as the cool, charismatic father, the actor’s easy-to-watch presence and enigmatically charming drawl offering sporadic checks on the surrounding melodrama. Together, the two illustrate great love and earnestness, even as they find themselves marginalising much of what comprises life in favour of their son.

Down the hall from Auggie we find one such marginalised figure, Via (short for Olivia, and played rather stunningly by 16-year-old Izabela Vidovic, underpinning luminousness with vulnerability), Auggie’s older sister who has been necessarily sidelined for so much of her youth, the toll of which is beginning to break her. “Auggie is the sun. Me and Mum and Dad are planets orbiting the sun” Via narrates at one point. Chbosky does grant Via the opportunity to occupy centre stage however, delving into her blossoming relationship with the well-to-do Justin (Nadji Jeter), and unpacking the gradual toll of a lifetime spent on the periphery. We see Via lie to Justin about being an only child, a symptom of the impossible to articulate challenge of her family’s life (a symptom too perhaps, of her longing to be free of Auggie’s shadow if for only a moment); we witness Via’s devastation when her mother’s attention is ripped from her just as she finally attains it. We see her, perhaps mistakenly, compare her social troubles to that of her brother’s, and we see her expressive great affection and maturity. It’s Vidovic who carries Wonder’s most touching moment, an ostensibly cliched performance of Our Town which transfigures into a cascade of passion and heartache.

We delve into the world of Jack Will (Noah Jupe), Auggie’s classmate reluctantly tasked with ingratiating Auggie to the fifth grade. We see the way Jack’s confliction between popularity and the genuine admiration he develops for the unjustly maligned Auggie wrestle; the rites of passage he undergoes via his outcast classmate.

We meet Via’s former best friend Miranda (Danielle Rose Russell), tasked with her own familial hardships, and who reflects on Via’s distinguished personality and family life with both envy and fondness.

Even Auggie’s chief tormentor, school bully Julian (Bryce Gheisar) is thoughtfully rendered; Chbosky, rather than demonising the apparent villain, instead opting to search for the root of that antagonism. Julian’s treatment, perhaps more than any other, is emblematic of Wonder’s rich humanity—the film’s empathy knows no bounds, the movie radiant in its refusal to tether its characters to archetypes.

At the hub of it all, of course, is Auggie himself, played by Jacob Tremblay (the brilliant child actor who sourced much of Room’s bludgeoning truthfulness), constantly evading that pit-trap of precociousness which has seized so many young characters in Hollywood. Once again, Tremblay brings an acute air of truth to this tale, albeit without skimming on the glee of childhood abandon. It’s he who in large part keeps Wonder’s feet planted on the ground, even as Auggie dreams of bouncing down the halls under the guise of an astronaut.

The genius of Wonder’s impressive breadth, taking the time to inhabit the world of a substantial ensemble, is twofold. For one, it offers relief for the narrative. To hone solely in on Auggie would have proven a no doubt exhausting exercise, a pummelling of affect and tribulation which might have verged on the tiresome. More significantly however, such breadth allows Wonder and its director to properly illustrate the vastness of its compassion. Via the film’s kaleidoscopic worldview, Wonder transcends the single-note, message-movie confines it teases, and becomes something altogether more universal and far-reaching– a layered treatise on inner-struggle which negotiates not only the discovery of self-worth and pride, but the trials of loneliness, peer pressure, and devotion; the courage required to do right, and to truly introspect. Wonder offers a sprawling emotional tapestry.

Perhaps it goes without saying that the film can’t help but occasionally cave to its sentiments. There are undeniably one too many crescendos of Marcelo Zarvos’ soft, triumphant score; one too many close-ups of wet eyes and devastated faces; one too many heavy plays for big emotion. Such misgivings are inevitable however. What matters in the case of Wonder is how those misgivings are qualified, to which the film responds with as much sincerity and empathy as its text permits. This is a profoundly thoughtful portrait of the human spirit, one which fights gallantly to fend off twee habits and champion sensitivity at every critical turn. It’s an ultimately successful endeavour, so much so that the film had the auditorium of my particular screening erupt into spontaneous applause upon its conclusion— that’s rare, and there couldn’t be a more legitimate testament to a film’s crowd-pleasing ability. That Wonder emerges on the other side of its story’s sentimental minefield all but unscathed is a stunning accomplishment. That the movie along the way exhibits the wells of complexity and depth reserved for only the most sophisticated dramas, is a miracle worthy of its plucky protagonist.

Rating:

3.5/4

Advertisements Share this: