by NONA BLYTH CLOUD

My father’s favorite poem was “Ulysses,” written by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (link below). However, his favorite poet was John Masefield (1878-1967), for his many poems about the sea. Coincidentally, the two men were Poet Laureates of the United Kingdom, Tennyson for 42 years, the longest serving poet, and Masefield for 37 years, the second-longest to serve.

John Masefield’s most famous poem is Sea Fever, and it is the Masefield poem my father loved the best. It meant a great deal to a man who grew up on the beaches and waters of Southern California, then traveled around the world on tramp steamers, but spent most of his adult life living in Arizona. When my dad retired, he fulfilled his dream of buying cruising sailboat and sailing away across the Pacific.

________________________________________________________________

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

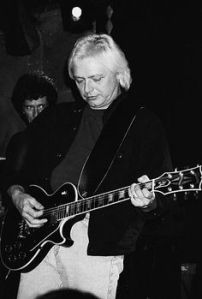

John Masefield was born on June 1, in land-locked Ledbury, a Herefordshire market town, the son of Caroline and George Masefield, a solicitor. His mother died giving birth to his sister when Masefield was only six, and he went to live with an aunt. His father died soon after. After four unhappy years as a boarder at the King’s School in Warwick, another land-locked place, he left to train for a life at sea, aboard HMS Conway. His disapproving aunt hoped this would break his addiction to reading. She must have been disappointed that during his years on board the Conway, he spent much of his time reading, writing and listening to yarns told by his shipmates.

________________________________________________________________

QUINQUIREME of Nineveh from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory,

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.

Stately Spanish galleon coming from the Isthmus,

Dipping through the Tropics by the palm-green shores,

With a cargo of diamonds,

Emeralds, amythysts,

Topazes, and cinnamon, and gold moidores.

Dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smoke stack,

Butting through the Channel in the mad March days,

With a cargo of Tyne coal,

Road-rails, pig-lead,

Firewood, iron-ware, and cheap tin trays.

________________________________________________________________

I didn’t find any information about why Masefield chose being a sailor as his way to make a living, but perhaps it was as far as he could imagine away from his previous existence. It was not to be a life-long commitment.

In 1894, Masefield boarded the Gilcruix, destined for Chile – a voyage so rough that for the first time he experienced prolonged sea sickness. He still recorded his experiences in journal entries: his delight in seeing flying fish, porpoises, and birds; awe at nature’s beauty; a rare sighting of a nocturnal rainbow. On reaching Chile, Masefield suffered from sunstroke and was hospitalised. He eventually returned home to England as a passenger aboard a steam ship. In 1895, Masefield returned to sea on a windjammer which was to round Cape Horn, destined for New York City. However, his dreams of becoming a writer and the hopelessness of life as a sailor overtook him, and he deserted ship in New York. After living as a vagrant for several months, drifting from place to place and surviving on odd jobs, he found work as an assistant to a bar keeper, before returning to New York City.

At Christmastime in 1895, Masefield read Duncan Campbell Scott’s poem, “The Piper of Arll” in the December edition of Truth, a New York periodical (link below). Ten years later, Masefield wrote to Scott to tell him what reading that poem had meant to him:

“I had never (till that time) cared very much for poetry, but your poem impressed me deeply, and set me on fire. Since then poetry has been the one deep influence in my life, and to my love of poetry I owe all my friends, and the position I now hold.”

For the next two years, Masefield worked at the huge Alexander Smith carpet factory in Yonkers, New York. The hours were long, and conditions grim, but he bought 10 to 20 books a week, devouring a wide range of classical and contemporary literature.

He returned home to England in 1897 as a steam ship passenger. In 1901, 23-year-old John Masefield met his future wife. Constance de la Cherois Crommelin was 35, educated in classics and English Literature, and taught mathematics. They would have two children, Judith, born in 1904, and Lewis, born in 1910.

Masefield worked for a time as a journalist at the Manchester Guardian, but by 1902 he was in Wolverhampton, in charge of the fine art section of the Arts and Industrial Exhibition. At the same time, his poems were being published in periodicals. His first volume of poetry, Salt-Water Ballads, was also published in 1902, the first book to include his poem “Sea-Fever.”

________________________________________________________________

A WIND’S in the heart of me, a fire’s in my heels,

I am tired of brick and stone and rumbling wagon-wheels;

I hunger for the sea’s edge, the limit of the land,

Where the wild old Atlantic is shouting on the sand.

Oh I’ll be going, leaving the noises of the street,

To where a lifting foresail-foot is yanking at the sheet;

To a windy, tossing anchorage where yawls and ketches ride,

Oh I’l be going, going, until I meet the tide.

And first I’ll hear the sea-wind, the mewing of the gulls,

The clucking, sucking of the sea about the rusty hulls,

The songs at the capstan at the hooker warping out,

And then the heart of me’ll know I’m there or thereabout.

Oh I am sick of brick and stone, the heart of me is sick,

For windy green, unquiet sea, the realm of Moby Dick;

And I’ll be going, going, from the roaring of the wheels,

For a wind’s in the heart of me, a fire’s in my heels.

________________________________________________________________

Masefield switched to writing novels, Captain Margaret (1908) and Multitude and Solitude (1909). In 1911, he returned to poetry, composing “The Everlasting Mercy,” the first of his long narrative poems, and within a year produced “The Widow in the Bye Street” and “Dauber.” Masefield was now widely known to the public and praised by critics; in 1912, he was awarded the Edmond de Polignac prize.

At the start of World War I, Masefield was old enough to be exempted from military service, but he joined the staff of a British hospital, Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, in Haute-Marne, France, serving briefly in 1915 as a hospital orderly. He later published an account of his experiences. The Masefield family found a country retreat for the next couple of years in Lollingdon Farm in Berkshire, which inspired a number of poems and sonnets under the title Lollingdon Downs.

________________________________________________________________

THE Kings go by with jeweled crowns;

Their horses gleam, their banners shake, their spears are many.

The sack of many-peopled towns

Is all their dream:

The way they take

Leaves but a ruin in the brake,

And, in the furrow that the plowmen make,

A stampless penny, a tale, a dream.

The Merchants reckon up their gold,

Their letters come, their ships arrive, their freights are glories;

The profits of their treasures sold

They tell and sum;

Their foremen drive

Their servants, starved to half-alive,

Whose labors do but make the earth a hive

Of stinking stories; a tale, a dream.

The Priests are singing in their stalls,

Their singing lifts, their incense burns, their praying clamors;

Yet God is as the sparrow falls,

The ivy drifts;

The votive urns

Are all left void when Fortune turns,

The god is but a marble for the kerns

To break with hammers; a tale, a dream.

O Beauty, let me know again

The green earth cold, the April rain, the quiet waters figuring sky,

The one star risen.

So shall I pass into the feast

Not touched by King, Merchant, or Priest;

Know the red spirit of the beast,

Be the green grain;

Escape from prison.

________________________________________________________________

Masefield was invited in 1916 to the United States for a three-month tour to lecture on English Literature. When he returned to England, he submitted a report to the British Foreign Office, and suggested that he be allowed to write a book about the failure of the allied efforts in the Dardanelles, which possibly could be used in the United States to counter any German propaganda. The resulting work Gallipoli was a success in America, and also encouraged the British people, lifting some of the disappointment felt after the Allied losses in the Dardanelles.

In 1918 he was asked back to America for a second lecture tour, spending much of his time speaking to audiences of American soldiers waiting to be sent to Europe. These speaking engagements were very successful, and on one occasion, a battalion of black soldiers danced and sang for him after his talk. He improved rapidly as public speaker, learning how to speak from his heart, rather than merely reading words.

In the 1920s, as a respected and successful author, Masefield and his family were settled at Boar’s Hill, not far from Oxford. Masefield took up beekeeping, goat-herding and poultry-keeping. The 1923 edition of his Collected Poems sold about 80,000 copies. Three more lengthy poems were published: Reynard The Fox, Right Royal and King Cole.

________________________________________________________________

IT’S a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds’ cries;

I never hear the west wind but tears are in my eyes.

For it comes from the west lands, the old brown hills.

And April’s in the west wind, and daffodils.

It’s a fine land, the west land, for hearts as tired as mine,

Apple orchards blossom there, and the air’s like wine.

There is cool green grass there, where men may lie at rest,

And the thrushes are in song there, fluting from the nest.

“Will ye not come home brother? ye have been long away,

It’s April, and blossom time, and white is the may;

And bright is the sun brother, and warm is the rain,–

Will ye not come home, brother, home to us again?

“The young corn is green, brother, where the rabbits run.

It’s blue sky, and white clouds, and warm rain and sun.

It’s song to a man’s soul, brother, fire to a man’s brain,

To hear the wild bees and see the merry spring again.

“Larks are singing in the west, brother, above the green wheat,

So will ye not come home, brother, and rest your tired feet?

I’ve a balm for bruised hearts, brother, sleep for aching eyes,”

Says the warm wind, the west wind, full of birds’ cries.

It’s the white road westwards is the road I must tread

To the green grass, the cool grass, and rest for heart and head,

To the violets, and the warm hearts, and the thrushes’ song,

In the fine land, the west land, the land where I belong.

________________________________________________________________

Beginning in 1924, he concentrated on writing novels, publishing twelve of them, from sea stories (The Bird of Dawning, Victorious Troy) to social novels about modern England (The Hawbucks, The Square Peg), tales of an imaginary land in Central America (Sard Harker, Odtaa) and fantasies aimed at children (The Midnight Folk, The Box of Delights).

He also wrote several dramatic pieces, but was taken by surprise when one, The Coming of Christ, ran afoul of a ban on the performance of plays on biblical subjects that went back to the Reformation and had been revived a generation earlier to prevent production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. A compromise was reached, and in 1928 it was the first play to be performed in an English Cathedral since the Middle Ages.

In 1930, Robert Bridges, the current Poet Laureate, died. Many felt that Rudyard Kipling was a likely choice; however, Kipling was then 65 years old (and had made public statements accusing Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Party of communist sympathies!) so King George V took Prime Minister MacDonald’s advice and appointed 52-year-old John Masefield, who remained in office until his death in 1967. On his appointment The Times newspaper said of him: “… his poetry could touch to beauty the plain speech of everyday life.”

Masefield’s first official commission as Poet Laureate was a memorial ode for the unveiling of the Queen Alexandra Memorial on Alexandra Rose Day (a charitable project of the late Queen), on June 8, 1932 at Marlborough Gate, London. Queen Alexandra was a Danish princess who was married to King Edward VII.

________________________________________________________________

So many true Princesses who have goneSo many true princesses who have gone

Over the sea, as love or duty bade,

To share abroad, till Death a foreign throne,

Have given all things, and been ill repaid.

Hatred has followed them and bitter days.

But this most lovely woman and loved Queen

Filled all the English nation with her praise;

We gather now to keep her memory green.

Here, at this place, she often sat to mark

The tide of London life go roaring by,

The day-long multitude, the lighted dark,

The night-long wheels, the glaring in the sky.

Now here we set memorial of her stay,

That passers-by remember with a thrill:

“This lovely princess came from far away

And won our hearts, and lives within them still.”

________________________________________________________________

It was set to music by Sir Edward Elgar, Master of the King’s Musick.

In 1937, Masefield was elected as President of the Society of Authors. He encouraged the continued development of English literature and poetry, and began the annual awarding of the Royal Medals for Poetry for a first or second published edition of poetry by a poet under the age of 35.

He took his post as Poet Laureate seriously, and produced a significant amount of verse, but also published three memoirs: New Chum, In the Mill, and So Long to Learn.

Masefield was finally feeling his age in the late 1950s. Then in 1960, his wife Constance died at aged 93, after over 50 years of marriage, and a long year of suffering. But he still worked, albeit at a much slower pace, and produced In Glad Thanksgiving, his last book, published when he was 88 years old.

________________________________________________________________

I have seen flowers come in stony places

And kind things done by men with ugly faces,

And the gold cup won by the worst horse at the races,

So I trust, too.

________________________________________________________________

In late 1966, Masefield developed gangrene in his ankle, which spread to his leg. He died of the infection on May 12, 1967. According to his wishes, he was cremated and his ashes placed in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Later, the following verse was discovered, written by Masefield, addressed to his “Heirs, Administrators, and Assigns”:

Let no religious rite be done or read

In any place for me when I am dead,

But burn my body into ash, and scatter

The ash in secret into running water,

Or on the windy down, and let none see;

And then thank God that there’s an end of me.

________________________________________________________________

The sentiments were echoed by my dad, in his instructions to me: “I don’t want a funeral or a memorial service. Just throw a great party, then take my boat out and scatter my ashes at sea.”

On a bright winter day, the boat rocking upon the waves, I read “Sea Fever” aloud, just before I leaned over the side and let the wind take his ashes for the “quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.”

________________________________________________________________

- “Ulysses,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/ulysses - “The Piper of Arll” – Duncan Campbell Scott’s poem which inspired John Masefield:

https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/piper-arll

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/john-masefield

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Masefield-British-poet

- https://mypoeticside.com/poets/john-masefield-poems

- The three-masted barque Kaskelot, photo by Rick Tomlinson

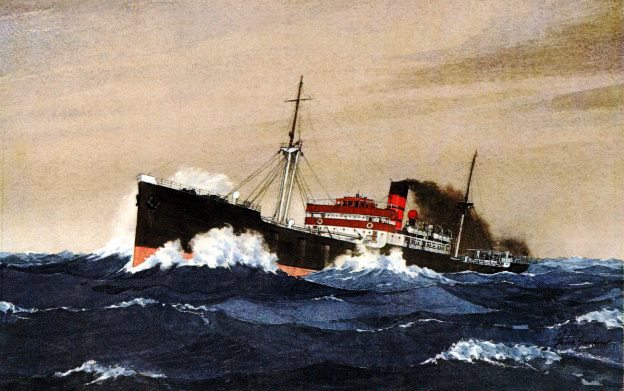

- SS Harmonious by uncredited painter

- John Masefield

- Wave at Lyme Regis

- Hills in Wittenham

- Bluebells in the Cotswolds

- 1908 Queen Alexandra, “Blue” portrait – by François Flameng

- Flowers in rock crack

- La Jolla sunset

Word Cloud photo by Larry Cloud

________________________________________________________________

Share this:- More