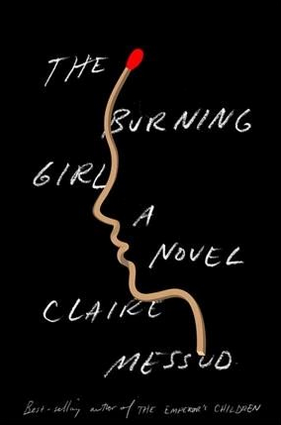

An interview done by Scott Simon on NPR with author Claire Messud about her novel, The Burning Girl, recently caught my attention.

The novel is a story of adolescent friendship, but it’s not labeled as YA. This distinction had me thinking of other novels I’ve enjoyed in the last few years in which the protagonists are not grown ups, but the readership is generally intended to be adult: books like Tell the Wolves I’m Home and We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

Simon asked Messud if anyone gave her trouble about her intended audience and how the book should be labeled. Her response:

When I was growing up, and maybe when you were growing up, too, YA was not a category that existed. There were books about young people. There were books about older people. And there were children’s books that were frankly written for children. But, otherwise, books were just for people. This is a book that is as much for a parent as a child, is as much for a teenager as a grandmother or a grandfather.

It’s a book about what it’s like to be alive and be human, I hope. For me, at least, and for the people – everyone around me that I know – these years are so formative and so central to who we become and how we interact with other people as adults in the world – that to see them as something only of interest to teenagers or adolescents themselves – I think that’s just missing so much of reality.

People often ask me what my target audience is for A Girl Called Problem, perhaps because the premise piques adults’ interest (a girl looking to challenge gender roles in rural, 1960s, post-independence Tanzania), but the protagonist is a kid. My simple answer: the publisher labels the readership as 9-13-year olds, but many of the readers I hear from are adults.

I’m delighted the young-adult and middle-grade genres have exploded since I was a child. There are so many books out there now that have the potential to feel truly relevant to a whole spectrum of young readers: nerds, cool kids, outcasts, struggling readers, action lovers, unusually mature (or immature) kids, poets, artists, city kids, hicks. But I also believe that really quality literature, whether it’s written for kids or adults, transcends age, as Messud suggests.

I’m revising a young adult novel right now, one set in the mountains of South India, and as I rework the dialogue or my descriptions of the feelings of the protagonist teenager and of her friends, I’m aiming to depict what feels like an authentic teen experience, but ideally also one that will feel interesting and fully human for adult readers. That’s a tricky balance. I encourage you to listen to the interview with Messud and to consider what you think makes young-adult and middle-grade fiction unique.

Advertisements Share this:- More