In You Must Change Your Life, Rachel Corbett elucidates the unlikely friendship between French sculptor Auguste Rodin and Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Not only was Rodin 35 years Rilke’s senior, but their personalities were polar opposites. Rilke was sensitive, delicate, refined, while Rodin was robust and carnal. At the time of their meeting in 1902, Rodin was famous and admired, while Rilke was still unknown. his poetic gifts unformed. Their meeting was transformative for them both. Rilke was transfixed by the older artist, and they developed a master-disciple relationship that lasted until Rodin’s death.

Photograph of Rainer Maria Rilke Photographer unknown

You Must Change Your Life provides a sketch of both artists’ biographies. Corbett includes information on the most significant relationships of the two men’s lives, especially the women who surrounded them. (I wrote a previous blog post here on one of these

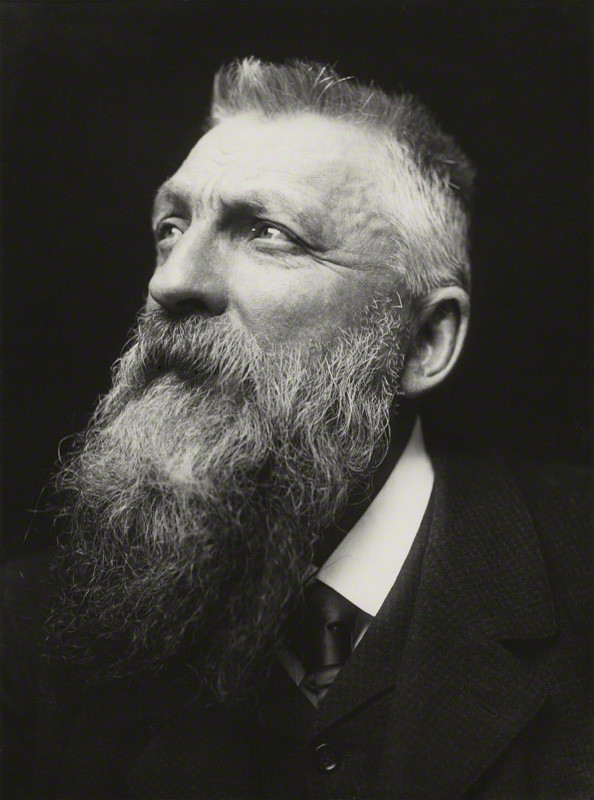

Photo of Auguste Rodin by George Charles Beresford

fascinating women: Lou Andreas-Salome.) Corbett is most interested, however, in exploring the process of creativity and artistic development. In doing so, she delves into the intellectual and artistic currents of late 19th century in order to explain to readers the influences on both Rilke and Rodin. She explores not only aesthetic theories, but also on other intellectual currents such as philosophy, psychoanalysis, and the newly explored concept of empathy. Corbett also illuminates the significance of particular places in creativity—especially the city of Paris, which has been the incubator of so many artists.

Of all the many influences on Rilke, Rodin was one of the most important. Rilke allowed himself to be like clay in his master’s hands, yearning to be shaped into something memorable. He learned many things from the sculptor, especially “the meaning of structure. [Rodin] had given [Rilke] the blueprint to build his poetry like a carpenter builds four walls around him” (246). Learning structure was immensely valuable to the poet.

However, Rilke also misunderstood some of Rodin’s advice, much to his detriment. Rodin urged Rilke to “travailler, toujours travailler” (work, always work). Unfortunately, Rilke followed this advice literally, sacrificing close relationships and many of the pleasures of his life in order to pursue his art more fervently. “He had sat around empty hotel rooms, stared at cathedral towers and caged lions, slept in empty beds. But deep within the body of this lifelong observer was the trace of a ‘still feelable heart’ that had been ‘painfully buried-alive by images,’” observes Corbett. Rilke had abandoned life “in anticipation of future payoff” (247).

It was only later that Rilke realized that “Rodin had not made any of the sacrifices that he, Rilke, had. Rodin was no martyr for his art. How did he live? Full of pleasure, and exactly as he pleased, it turned out” (247). At first, Rilke felt disillusioned when he realized his mentor was not what he thought he was. Eventually, though, Rilke realized that nobody, no master, could tell their disciple how to live. The artist has to figure it out for themselves. The important thing about art, Rilke realized later in his life, is that “there was never anything waiting on the other side: There was no god, no secret thing, and in most cases no reward. There was only the doing” (247). Rilke does, of course, become a great poet. Corbett does not suggest that Rodin was the only reason for Rilke’s greatness. He was, nonetheless, a pivotal figure in Rilke’s artistic development.

I found Corbett’s book fascinating. I would recommend it to readers who are interested in the arts, in creativity, in the cultural and intellectual currents of late 19th century Europe, or even in the city of Paris. The book contains a number of different “threads,” of which I only touched on a few here. Perhaps one could fault Corbett for trying to cover too many different topics, leaving a somewhat “meandering” feel to the book. I, however, enjoyed her excursions into some of the facets of fin-de-siecle European art.

Advertisements Share this: