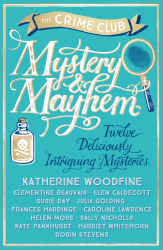

Immediately prior to interviewing Robin Stevens for The Men Who Explain Miracles, I discovered that she had written a short story for 2016 YA anthology Mystery & Mayhem. And then I discovered that the first three stories in the collection were impossible crimes and, well, you can guess what happened next…

The stories are aimed at the younger end of the reading market, but we know that’s no excuse for laziness and each demonstrates a firm grasp of the key ideas of detective fiction that it’s great to see being utilised by the writers who have taken up this mantle. Let’s not get too beard-stroking about this, but credit where it’s due, after all: a lot of work is done in making these stories fair play, when in fact the laying of clues is often the first thing to go in such undertakings. I want to celebrate it when I see it, and I can really see the work put in here.

First up is ‘Emily and the Detectives’ by Susie Day, which sets up in its first 8 pages a universe I dearly want to spend more time in: the prodigious young Emily already more than an intellectual match for the amateur detective Lord Copperbole who courts her scientist father’s aid in (of course) only the most baffling of cases. “The Mystery of the Eminient Zoologist’s Wife’s Mother’s Spoons” — started on the third page and concluded on the fourth — was probably where I fell in love with Day’s writing and we’re not even at the locked room death of Vicountess Fromentin at that point. There’s so much verve and joy and lightness in the prose that only a hard and unloving heart won’t be swept along.

Anyway, to business: the Vicountess goes to dinner, returns home, and is found dead the next morning with her bedclothes slashed and a suitably ominous word etched on the floor (shades of A Study in Scarlet, especially given the Victorian setting):

Immediately prior to interviewing Robin Stevens for The Men Who Explain Miracles, I discovered that she had written a short story for 2016 YA anthology Mystery & Mayhem. And then I discovered that the first three stories in the collection were impossible crimes and, well, you can guess what happened next…

The stories are aimed at the younger end of the reading market, but we know that’s no excuse for laziness and each demonstrates a firm grasp of the key ideas of detective fiction that it’s great to see being utilised by the writers who have taken up this mantle. Let’s not get too beard-stroking about this, but credit where it’s due, after all: a lot of work is done in making these stories fair play, when in fact the laying of clues is often the first thing to go in such undertakings. I want to celebrate it when I see it, and I can really see the work put in here.

First up is ‘Emily and the Detectives’ by Susie Day, which sets up in its first 8 pages a universe I dearly want to spend more time in: the prodigious young Emily already more than an intellectual match for the amateur detective Lord Copperbole who courts her scientist father’s aid in (of course) only the most baffling of cases. “The Mystery of the Eminient Zoologist’s Wife’s Mother’s Spoons” — started on the third page and concluded on the fourth — was probably where I fell in love with Day’s writing and we’re not even at the locked room death of Vicountess Fromentin at that point. There’s so much verve and joy and lightness in the prose that only a hard and unloving heart won’t be swept along.

Anyway, to business: the Vicountess goes to dinner, returns home, and is found dead the next morning with her bedclothes slashed and a suitably ominous word etched on the floor (shades of A Study in Scarlet, especially given the Victorian setting):

[T]he newspapers…had begun to report what they were calling The Case of the Deadly Bedchamber…a case so baffling that the police were ‘probably, like, not even going to bother’, according to a source.While this one isn’t technically fair play, I do think Day does a great job in pushing it about as close to fair play as one could get without tipping her hand ridiculously obviously. It also demonstrates the principle of research, to be willing to work out what happened rather than simply relying on intuitionist brilliance. Day walks the line between genuine crime solving and out-and-out parody perfectly, including subtle implications of certain social attitudes at the time, and the thread left deliberately hanging once the mechanics of the crime are solved is…just gorgeous. And it all ties up beautifully at the end. Someone commission a series of novels featuring these characters, please.

Exactly.

Elen Cadlecott‘s story ‘Rain on My Parade’, then, has a tough act to follow, and benefits from a superbly unusual impossible situation: a costume designed and made over the preceding weeks to be worn in a carnival that is somehow destroyed overnight despite being in a locked workshop. There’s something more than a little Jonathan Creek about this situation and the resolution — we’re more into fair play territory here, I’d say, and it’s quite smoothly done — in that it’s all just off-kilter enough to really capture the imagination. I have a feeling it could even be original in both conception and solution — it could also not, it’s absurdly difficult to say that with any certainty, but there’s the genuine spark of superb creativity about this that does so much more than simply reheats old ideas. And the seemingly less-impactful problem of a mere dress being ruined benefits from being played as seriously as any murder:They moved slowly, the way hospital visitors might walk into an intensive care ward.Here we also get the important concept of a clue seen the wrong way around, and see how by quickly misreading a piece of data a huge amount of time and energy can be wasted by our detective. The importance of this in the context of detective fiction cannot be overstated, and Caldecott makes it a very simple idea that’s easy to both follow up and dismiss — a great piece of misdirection and assumption-jumping-to. And, indeed, that ability to take something and not appreciate the precise form of its significance, especially in such a visual way, is something the best of these mysteries have exploited for decades now. It’s a clever story that does well to establish some false suspects and also work as the kind of problem that it makes no sense to call the police in on; if you want to give your amateur detective free reign, a personal problem of this ilk is a great way to go.

Yeah, sure. Sure thing, guys.

Speaking of the police, the entrance of the police officer in ‘The Mystery of the Green Room’ by French academic and author Clementine Beauvais is completely marvellous:“I’m very sorry for your loss and all, but we often jump to conclusions when in fact there’s generally a very simple expla–”Quite who stabbed Great Uncle Bill Leroux through the chest as he sat alone in his locked bedroom will be to the regular reader of this kind of thing rather plain, but 35 year-old me isn’t the intended audience and so I shall not gripe and, anyway, Beauvais does two far more important things in this story very well indeed. Firstly, she handles mood perfectly, giving us a murder both suitably savage but not graphically described and contrasts this with the horror of the adults and the ghoulish delight of the youngsters present. Secondly, and most importantly, we get a false solution of sorts, with one aspect of the case given a how (just about, the shortfall being deliberate) but then falling down (again, deliberately) on the why. That distinction of not just working out isolated events but of forming them into an important cohesive sequence is played expertly. The bit with the canaries is rather odd, though. The whole why of that strand eludes me. The locked room nerd in me — actually, I think the rest of me is now contained within the locked room nerd in me, sort of like a Klein bottle — is also delighted to see a few callbacks to French subgenre-changer The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907): the title, yes, and the family name of Leroux, but also the aforementioned policeman being named Mabille (my ball, if my French holds up) in reference to Leroux’s Rouletabille (roll your ball, I seem to remember — yes, I could look it up, but I’d rather be honestly wrong than pretend recall), and…well, some others I’ll let you discover. It makes little difference overall, but at least implies a certain awareness of what has come before…something that I feel is going to be increasingly important if this subgenre is going to continue to develop in the decades ahead.

Um, don’t you have homes to go to?

~ So, well, dammit, I remain very jealous of the quality of genre-aware detective fiction that the current younger generation are being exposed to. When I was nine I was reading Dick King-Smith (probably), and then made the leap to Tom Clancy’s jingoistic and horrible Clear and Present Danger…no wonder it took me so long to find my niche. The standard of these three stories alone bodes well for the remainder of the collection, which may or may not feature on here at later dates. Searching for more books by the Crime Club, the collective name under which this is published, currently brings up nothing else by this clutch of authors, but perhaps that will change in time. Watch, I suppose, this space. If I hear anything I’ll let you know. Though probably on Twitter, to be honest, so watch the space to the right of this. Share this: