Originally posted on Blogger on 21 February 2016

Thomas Nickerson’s drawing of the Essex

Thomas Nickerson’s drawing of the Essex

In honour of Owen Chase, Thomas Nickerson, Benjamin Lawrence, Thomas Chappel, Seth Weeks, William Wright, Charles Ramsdell, and George Pollard, Jr – the survivors of the Essex

In August 1819, two whaleships – the Essex and the Chili – sailed out of their home port of Nantucket. Only the Chili would return in 1822. The story of the Essex became the Titanic story of its day. Around the world and up and down the East Coast, word spread of the 238-ton whaleship that had been hit by a whale thousands of miles from the west coast of South America.

The Essex had been partially rebuilt for the voyage that was to come and her owners were planning on rebuilding the rest of her soon after she returned. Nantucket had a fleet of twelve to fifteen – possibly more – whaleships at the time. Of these the Essex was one of the smallest craft. Her keel had been recoated with copper to reinforce her hull and several of her ropes had been replaced.

The man who would captain the Essex on this voyage was George Pollard, Jr. The Pollards were one of the original families of white settlers on Nantucket. Pollard had been the previous first mate on the Essex. He – like other members of the crew – had sailed on her several times and knew the reactions of the ship.

The new first mate of the Essex was Owen Chase. Whereas Pollard had gotten to where he was through his family connections – his father was one of the shareholders of the Essex and a former whaling captain himself -, Chase had become first mate on his own merits. Chase’s mother had died when he was young and his father wasn’t in the picture, making Chase and his brother, Joseph, virtual orphans. Children without fathers wasn’t a rarity on Nantucket – several of the teenagers on the Essex were without fathers by the time they sailed in August 1819. Like many of them, Chase had found his place on the docks with other boys like him and found his way onto a Nantucket whaling ship at the age of eighteen. Chase would rise quickly through the ranks of a whaling ship first as a sailor, then as harpooner. In August 1819, when he was risen to first mate on the Essex, he was twenty-two. If the Essex hadn’t been stove by a whale in November 1820, Chase would’ve likely made captain by the age of twenty-five.

One of the problems of the Essex was Pollard was a captain with first mate tendencies and Chase was a first mate with captain tendencies. Pollard was a man who could be easily swayed. He ran his ship in a democratic style, rather than pulling rank and giving orders the way captains were expected to in the 19th century. Chase on the other hand, was capable of giving orders firmly and quickly, but in a world where first mates were expected to curb their temper, voice, and reactions, it wasn’t acceptable. The two would clash several times over the course of the upcoming voyage, but it world only truly become a problem in November 1820.

The voyage the Essex left for on 12 August 1819 would prove to be its last. It would be one of the last ships to leave the harbour in the year 1819 with the winter storms fast approaching and needing to get to the Pacific Ocean where many of the right and sperm whales they were hunting now made their homes.

The names of the right and sperm whales both come from the whaling tradition that killed them nearly to extinction. The right whale gets its name because it was the so-called “right whale to kill”. This was before the sperm whale was discovered. The name of the sperm whale comes from the substance called “spermaceti” that’s found in the head of this particular whale. It was one of the most valuable parts of the whale to whalers.

The 21-men crew of the Essex boasted men from Nantucket, other towns in Massachusetts, as well as New York and England. They wouldn’t have to wait long for tragedy to hit them, and in the next year and a half the divide between Nantucketers and the rest would become stronger. Seven of these men were also African American and the racial divide wouldn’t be as strong. On a whaleship – to a certain extent – it didn’t matter where you were from or what your race was. What mattered more was whether you could succeed at the job you were required to do. When you were out in the open ocean and the only person who could rescue you was African American – or visa versa – whalemen chose to be saved.

While sleeping quarters were still divided into Nantucketers and non-Nantucketers – it was this way on the Essex – there wasn’t near the stigma about African Americans at sea that there was on land. As long as they could do what was asked of them, there wasn’t any reason to drive them further onto the edges of society. And out in the open ocean, searching for whales, who knew when a whale would become angry and overturn a whaleboat – or two.

On 15 August, there was the first hint of disaster to the Essex and an escalation in the relationship between Pollard and Chase. Until this moment, the Essex had been doing quite well, making good time in taking her crew to the Azores islands off the west coast of Africa. On that day, as they were heading towards Africa, a storm blew up. Chase wanted to roll up some of the sails, giving the winds of the storm less of a chance of taking control of the ship and leaving the crew to the mercy of the storm. Pollard countermanded the first mate’s order, ordering more sails lowered. The crew was frozen on the decks and in the ratlines, not sure whom they should obey: their first mate or their captain. Pollard’s order overruled Chase’s and the sails were dropped. As the Essex sailed further into the oncoming storm, the sky darkened and the sails were pushed back against the masts. At around this point, Pollard conceded that Chase had been right and gave the order to draw the sails in. Chase answered that it was too late to do anything now. The men of the Essex couldn’t do anything more than hope and pray that their aged ship could last through one more squall.

The Essex came through that squall not without issue. When the Essex emerged from it, she had some tattered sails, had lost one whaleboat, severely damaged another and her captain and first mate were arguing again. Pollard wanted to turn back to Nantucket, but Chase said they had to continue. That it would be better to go on with a damaged ship and no spare whaleboat (whalers often damaged to whaleboats) than to return to Nantucket, their families and the owners of the Essex without anything to show for it. In this, Chase won, and the Essex continued down the east coast of South America toward Cape Horn on the other side of which lay the Offshore Ground.

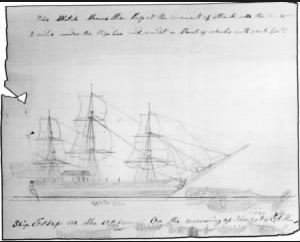

About halfway down South America’s east coast, they sighted their first whale. The moment the lookout alerted the rest of the crew, everyone sprang into action. Three men were left on the Essex to guard the ship, while the rest were split between the three whaleboats. With the whaleboats loaded with men, rope, harpoons, lances, and oars, they were lowered into the ocean and the chase was on.

With the boatsteerer in the bow and the mate in the stern, the whaleboats flew over the open ocean after the whales. They rowed fast, the small boats cutting through the waves, splashing everyone onboard.

As the boats closed in on the pod of whales, they would separate, going for different prey. When the boat was close, the boatsteerer would launch the harpoon at the whale. When it struck, its head buried in the whale’s blubber, the most dangerous part began. It was the one piece of whaling that wasn’t one hundred per cent in the hands of the crew of the whaleboat. The whale would sense the barb and dart forward, diving under the waves, heading away from the ship, dragging the boat along behind them from miles. It was known as “the Nantucket sleigh ride”. No ship on the ocean in the 19th century reached the speeds of a whaleboat pulled by a whale.

A whale can swim for many miles and can hold its breath for far longer than a human. Whales are generally passive creatures, but every whaleman knew that once a harpoon buried itself into a whale’s side, the whale would become panicked and angry. The crews knew the danger and the risk of it, that there was potential for the whale to flip the boat, dumping men and supplies into the ocean. The whale could then escape.

This is what happened to Chase’s boat at the first whale sighting. The next day, they went out again and success was theirs. The Nantucket sleigh ride was only the beginning.

[WARNING: Blood and gore in the following section]

When the whale had stopped, the mate would take the killing lance and throw, aiming for the heart and other vital organs. These organs, however, are covered in a thick layer of blubber, forcing the mate to sometimes repeat the process several times. When the lance found its mark, the whale would die, choking on his own blood. The spout would into a fifteen to twenty foot geyser of gore, which would shower down upon the men. Eventually, the whale would fall motionless. The job, however, was not done. The men in the boat had to drag the whale back to the ship. A journey that had only taken minutes now took hours.

When Chase’s whaleboat returned to the Essex in the dark, the real work could begin.

Throughout whaling history, there have been descriptions of the process of peeling blubber off a whale like peeling an orange. The reality was very different. The start of a strip was hacked away from the body and a hole was made in the centre of the top of the section. A giant hook was threaded through the hole and the hook was pulled up by ropes, pulling the strip of blubber with it as the mates hacked away. The strip was gradually torn from the carcass until a twenty-foot long strip hung from the rigging, dripping blood and oil onto the deck. The piece was cut from the whale and lowered into the blubber room to be cut into smaller pieces to be boiled down into oil. This oil would then begin to fill the barrels in the hold.

After the blubber had been stripped, the whale was decapitated. The head was hauled onto the deck where a hole was cut in the top revealing the cavity of spermaceti if it’s a sperm whale. Spermaceti is a clear high-quality oil that was used for ointments, candles, and cosmetics. Because of its importance, all the spermaceti had to be taken out. Sometimes this required one or two men – usually the cabin boy – to climb into the head and scoop it out. By the time all the spermaceti had been removed, the decks were slick with oil and blood.

The intestines were opened searching for ambergris, one of the most sought after substances. It was used in perfumes and fragrances. Ambergris and spermaceti were the most valuable substances to come from the whale.

The try-pots

The try-pots

The iron try-pots were boiling and full of blubber by now. The blubber had been cut into foot square chunks, which were then cut again into inch-thick slabs, resembling the pages of a book. Wood was used to start the fires, but once they were going, the crispy pieces of blubber were skimmed off the surface and thrown on the fires below. In this way, the fires melting the whale’s blubber were fed by the whale itself. While economical, the fires produced a thick blue smoke with a stench so rancid, no one who ever smelt it forgot it.

[If you stopped reading because of the above warning, start up again here.]

The meat, bones and guts were thrown overboard. They held no value to the whalers who were after the whales for their oil and perfume-making products, not a food source.

It took the Essex more than a month to get around Cape Horn. In the shipping world, Cape Horn is notorious for the destruction it has done to ships and the dangerous winds that can blow a ship off course. These winds cause the currents around the tip of South America to become more violent than they would be normally, forcing ships to be more careful in these areas.

Once on the west coast of South America, having left nearly empty Chilean waters behind them, the Essex began having success in their mission. They ran into more whales in the Pacific than they had on their trip through the Atlantic. In two months, they boiled down 450 barrels of oil – about eleven whales. High winds and rolling seas plagued them though, making every aspect of whaling – from trying out to raising and lowering the whaleboats – more dangerous. The boats were in a near constant state of repair from banging against the sides of the ship.

At one of the island stopovers, where Pollard was getting news from other whaling captains, one of the African Americans onboard – Henry De Witt – deserted. While this was an effect on the crew, it wasn’t uncommon. Pollard had heard word, however, from other whaling captains, that there was a new whaling ground and he wanted to reach it by November. With time running out to find a new man, the Essex left the island with a crew of twenty, leaving two people to guard the ship while the others were out in the whaleboats.

The Essex headed off for the Offshore Grounds via the Galapagos Islands. While sailing towards them, they killed two more whales, reaching the halfway point of what the Essex could hold. Thoughts began turning towards Nantucket and home. But before these thoughts could take hold firmly, the Essex developed a leak. While they stopped on Hood Islands for repairs, Pollard took advantage to refresh their food stores with Galapagos tortoises.

In less than a week, 180 tortoises were collected. The tortoises were mostly stacked in the hold, but a few were left to roam the deck, while the crew sailed to nearby Charles Island. Another hundred tortoises were collected and letters were left to be picked up by ships returning home. And it was on Charles Island where Thomas Chappel, Matthew Joy’s boatsteerer, decided to play a prank. While the other nineteen men searched for tortoises, Chappel lit a fire in the underbush. It being late October and the height of the dry season, the fire quickly burned out of control. It surrounded the tortoise hunters and cut off their route back to the Essex. They had to run through the flames. Clothes and hair were singed, but no serious injuries acquired by the men.

The island, however, was not so lucky. By the time the Essex left, the island was ablaze. All the men were angry that one of their own had done such a thing, but Pollard swore he’d do something terrible to the man responsible. Chappel wisely didn’t admit to anything until much later. When Nickerson returned to Charles Island many years later, the island was still a blackened mass among the lush flora and fauna of the other Galapagos Islands.

By November 1820, the crew knew they only had a few more months of whaling left before they would have to return to South America if they wanted to avoid the entire crew succumbing to scurvy. Tensions were high amongst the officers of the Essex, forcing Chase to resume his post as boatsteerer and forcing Benjamin Lawrence to the back. Lawrence was humiliated, but soon it wouldn’t matter. A whale came up under their boat, capsizing it, sending men and supplies into the ocean.

Four days later, on 20 November 1820, the sun rose on a bright clear day. A slight breeze rolled through the air. The three whaleboats were lowered into the water and they set out for what looked to be a promising day on the horizon. It was 08:00.

Chase, in the bow and holding the harpoon again, directed Lawrence to steer the boat close to a whale. Lawrence followed the order, but he went so close, that as soon as the harpoon struck, the whale struck the boat. Chase cut the harpoon line before the whale could flip them into the water. With their shirts tucked into the hole and one man bailing, they rowed back to the ship and pulled the battered boat onto the deck for repairs. Chase wanted to get back out into the water. Partially forced by the fact Pollard and Matthew Joy – the second mate and Chase’s friend – had already caught whales. Chase began repairing the boat as quickly as he dared.

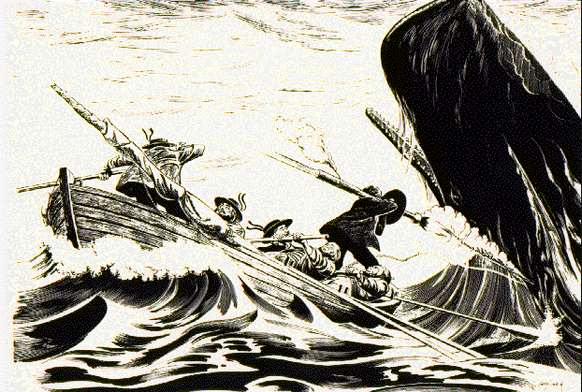

While the men waited for the repairs to be done, Thomas Nickerson, the fourteen year old cabin boy, took control of the helm, and began steering the Essex towards where Pollard and Joy had been dragged by their whales. Nickerson was looking ahead, when he saw something off the port bow. It was a male sperm whale, about eighty-five feet long, the biggest they’d ever seen. It was also acting strangely. It wasn’t fleeing in panic. It was floating quietly. At first, no one thought it was a threat. Then it began to move, picking up speed. It aimed at the Essex‘s port side. Chase shouted orders to Nickerson, but before Nickerson could act, the whale struck the ship. Everyone was amazed as they stood up. Never in the history of Nantucket whaling, had a whale turned on a ship. The Union had struck a sperm whale at night in 1807 and sunk, but that wasn’t what had happened on that November morning. This was a whale attacking a ship.

The whale dove under the ship and reappeared on the other side. Driven by instinct, Chase grabbed a lance, but as he readied himself to throw it, he noticed the whale’s fluke was close to the rudder could be damaged if he threw the lance. Chase decided they were too far from land to take the risk. Later, this moment would come back to haunt him. The whale swam away from the Essex, then returned. Chase called for Nickerson to change course, but it was too late. The whale struck the ship a second time, beneath the anchor. Water poured in, filling the hold. The whale swam off, never to be seen again, leaving the Essex and her crew to their fate.

The steward, William Bond, went below and rescued Pollard’s and Chase’s trunks and the navigational equipment. Chase and his men pushed the spare whaleboat into the ocean. The deck was only a few inches above the water.

Pollard’s boatsteerer, Obed Hendricks, was the first of Pollard’s or Joy’s crews to notice anything wrong. At his cry, Pollard and Joy cut their whales free and rowed towards the Essex, where eight men were getting into the spare whaleboat. The Essex had come to rest on her side on a sand bar. The whaleboats of Pollard and Joy drew up within yelling distance of Chase’s. It was then that Pollard and Chase had the now famous exchange:

“My God, Mr Chase,” said Pollard, “what is the matter?”

“We have been stove by a whale,” Chase replied.

Thomas Nickerson’s drawing of the whale attack

Thomas Nickerson’s drawing of the whale attack

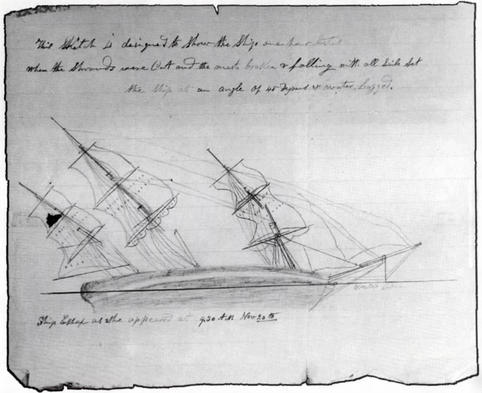

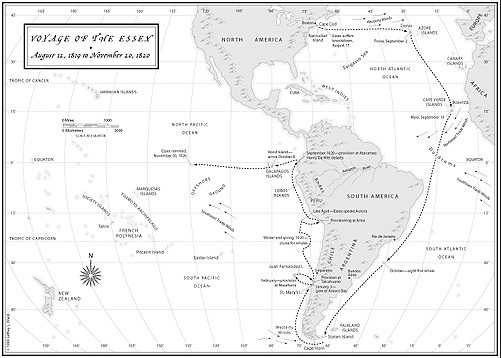

The last voyage of the Essex

The last voyage of the Essex

Food and water was taken from the wreck. The masts were cut away to twenty feet above the hull. Two casks of bread, six hundred pounds of hardtack, several casks of freshwater, a musket, two pistols, a small canister of powder, and two pounds of nails were extracted from the wreck, and divided among the three whaleboats. Several Galapagos tortoises and two hogs escaped and swam to the boats. The whaleboats tied up to the Essex for the night, leaving a hundred yards of line between the boats and the ship.

The next morning, the masts of the Essex were used to make masts for each of the whaleboats and the sails were taken down and with needles and thread from Chase’s trunk, new sails were created and attached to the new masts. Timber was town and used to raise the sides of the whaleboats in an attempt to protect themselves and their provisions from the salty spray. When darkness fell, they tied up to the Essex for the last time.

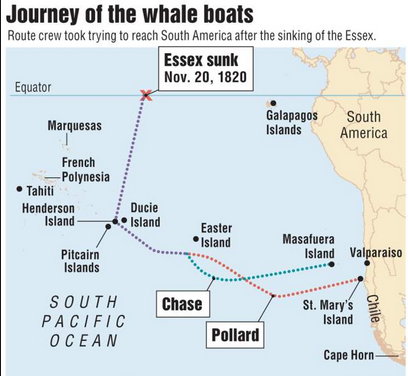

The morning of the second day after the sinking was met with a disturbing sight. The Essex was falling apart. The casks of whale oil were opening and leaking across the the surface of the ocean. It coated the sides of the boats and came in over the sides. The boats became dangerous to move around in. In the afternoon, Chase, Joy, and Pollard gathered in Chase’s whaleboat, spread their charts before them and began discussing a plan. Pollard wanted to sail for the Society Islands. Chase and Joy disagreed, both wanting to head for South America. The islands of the Pacific were known to have cannibals, whereas whaling ports were scattered up and down South America’s coast. Pollard succumbed to Chase and Joy, once again proving he wasn’t a strong leader. If the crew had followed Pollard’s suggestion, it is likely more of the crew would’ve survived.

With a plan decided, Pollard, Chase, and Joy split the men between the boats. In its bad condition, Chase’s boat was kept at six, while the boats under the command of Pollard and Joy would carry seven each. The Nantucketers of the Essex would also look out for their own. Ties of family and friendship were already strong, and the disaster made them even stronger. In the choosing of men, rank also played a part. Pollard, as captain, would get five Nantucketers in his boat, Chase would get two, and Joy, being the most junior officer, and not a full Nantucketer – his family moved to Hudson, New York – was left with none.

The three boats together. Their reasons for this were practical, as well as bonds of friendship. With not enough navigational equipment to go around, Joy wouldn’t have a way find where they were if his boat was separated from both Pollard’s and Chase’s.

The next morning – the first day away from the Essex – Chase discovered a pencil and ten pieces of writing paper in his trunk. As first mate, he had been in charge of the Essex‘s logbook. With the official book at the bottom of the sea, these ten pieces of writing paper would become Chase’s log of the next ninety-three days and one of the best accounts of what happened to the twenty men of the Essex on the open ocean.

Two days later, the waves became larger and Chase’s boat began to sink. Chase and Pollard nailed a fresh plank to the outside, but much of the hardtack had been soaked with sea water and thus became the worst thing for their already water deprived bodies. That night Pollard’s boat was attacked by a whale, requiring repairs to his boat the next morning.

Ten days in, the first of the tortoises was eaten to the delights of men who had been living on bread, it was a joyous occasion.

The last of the damaged bread in Chase’s boat was eaten on 3 December. It was a turning point. They were still dehydrated, but without the excessive salt in their systems, they all began to feel better. At around 22:00, Chase and Pollard lost track of Joy, but his boat was soon discovered with the help of a signal light. Two nights later, Chase’s boat became separated. When Chase fired his pistol to find the other two, Pollard, Joy, and Chase decided if they lost track of each other again, they wouldn’t try to find each other.

On 9 December, Pollard’s boat disappeared again. Chase and Joy discussed what to do. They knew they should listen to the plan, not look for lost men and continue on their journey. They ignored their own plan and waited for Pollard. The next morning, when someone saw a sail, their wait paid off and Chase and Joy rejoined Pollard.

On 15 December, Chase’s boat appeared to be taking on more water than usual. One of the planks on the bottom was loose. To solve this problem, it was clear one of the men would have to take the hatchet and bang it back into place. Though his skills as a harpooner had been called into question, Lawrence took the task and was successful.

They had been kept in one spot on the ocean because they needed wind to fill the sails and help them on their way. By that afternoon, Pollard proposed they receive double rations during the day and row at night. The men agreed, but after several collapsed, they could not continue.

On 20 December, nineteen year old William Wright sighted land. It was Henderson Island.

The three boats moored at Henderson Island. After one of Chase’s men discovered water, they dragged the boats up onto the beach and stayed there. They thought they were on Ducie Island. The next day a spring was found and fish and birds were collected. They decided to stay another four or five days to regain their strength and repair the whaleboats more thoroughly.

Six days later, the Essex crew decided to abandon the island. Pollard making the announcement, along with the fact the boat crews would remain the same. It was then that Thomas Chappel, Seth Weeks, and William Wright spoke of their own plans. They would stay behind on Henderson Island. No one objected, but before leaving, they left behind everything they could to help Chappel, Weeks, and Wright in their survival.

At around 10:00 on 27 December, the seventeen remaining men got into the three boats and left Henderson Island. Chappel, Weeks, and Wright didn’t come to say goodbye.

***

On 8 January 1821, Matthew Joy made a request. He wanted to be transferred to Pollard’s boat. He knew was he dying, and in his own boat he was surrounded by an off-islander and four blacks. He wanted to die among his own people. His request was granted. By 16:00, Joy was dead. The three boats came together. Joy was sewn into his clothes, they tied a stone to his feet and they committed him to the sea.

With Joy dead and his boatsteerer, Chappel, having stayed on Henderson Island, Pollard ordered his boatsteerer, Hendricks, to take control of Joy’s boat. Soon after, Hendricks realised there was only enough hardtack in his boat to last two or three more days.

During the night of the following day, Chase became separated from the others. All three boats continued on, keeping hope that they would reconnect. On 14 January, Hendricks ran out of food. Not being able to begrudge his former boatsteerer of food, Pollard shared his stock, knowing that in a few days there would be none left. In his boat, Chase was also forced to reduce the rations to make supplies last. That night Chase forgot to lock his trunk and Richard Peterson, the black, stole some bread. One of the others informed Chase and Peterson had to plea for his life. His life was not to be much longer. On 20 January, Peterson refused his ration, saying:

“It may be of service to someone, but can be of none to me.”

The next day, he died. His body, like Joy’s, was committed to the sea. His was the last body the men of the Essex honoured.

On the same day as Peterson’s death, Lawson Thomas, one of the blacks on Hendricks’ boat died. With not enough hardtack a question cropped up. Should they bury the body at sea or should they eat it? Survival instinct won out. Thomas became the first man of the Essex to be eaten. Two days after they finished eating Thomas, another black, Charles Shorter, died. He too became food for the men or Pollard’s and Hendricks’ boats.

While the men in Chase’s boat survived, though exhausted and starving, Isaiah Sheppard and Samuel Reed – both black and in Hendricks’ and Pollard’s boat respectively – died in quick succession on 26 and 28 January. The night following Reed’s death, Pollard looked up to speak to Hendricks, and discovered the whaleboat containing Hendricks, Bond and Joseph West had disappeared. Pollard and his men – three teenagers – were too weak to try to find the missing boat.

On 6 February, having eaten the last of Reed, sixteen year old Charles Ramsdell proposed drawing lots. It was common practise in survival situations, but Pollard still refused at first. When Pollard’s cousin, Owen Coffin, seconded Ramsdell’s proposal Pollard looked at the three teenagers in his boat. They were all close to death to starvation. Pollard finally agreed. They drew lots using scraps of paper. The lot fell to Coffin.

“I’ll shoot the first man that touches you,” Pollard reportedly said. “I’ll take the lot myself.”

Eighteen year old Coffin responded: “I like it as well as any other.”

They drew lots again to see who would kill him. It fell to Ramsdell. Ramsdell refused to kill his friend. Coffin gave Pollard a message to bring to his mother if Pollard survived and laid his head on the gunwale. He was killed and his body eaten.

On Chase’s boat, they hadn’t moved for several days because of a lack of wind. On 28 January, it picked up and they began moving again. The day Coffin died, Isaac Cole gave up. Chase tried to change Cole’s mind, but like Peterson before him, Cole had made his decision. Unlike Peterson, however, Cole’s death wasn’t calm. Cole ranted and raved in a fevered state. He died two days later.

On 9 February, Chase spoke with Nickerson and Lawrence about using Cole’s body for food. After a conversation and removing Cole’s organs and limbs, the rest of the Cole’s body was committed to the sea.

Two days later, in Pollard’s boat, Barzillai Ray succumbed. Now Ramsdell and Pollard were alone with the body of Ray and the bones of Coffin and Reed to keep them alive.

On 14 February, when Chase, Nickerson, and Lawrence ate the last of Cole. Nickerson lay back in the boat and Chase could tell he was giving up. Lawrence had clung to hope throughout. He’d watched Peterson and Cole lose their battle with it and now he was watching the same with Nickerson, but Lawrence fought it.

Four days later, Chase, Nickerson, and Lawrence were rescued by the Indian.

Three hundred miles away, Pollard and Ramsdell pushed on. On 21 February 1821, they were rescued by the Dauphin and Pollard told the story of the Essex for the first time the captains of the Dauphin and the Diana.

On 25 February, the Indian pulled into Valparaiso, Chile. Chase, Nickerson, and Lawrence were transferred to the U.S.S. Constellation and Chase told the captain about Chappel, Weeks, and Wright who were still on Henderson Island. The captain promised Chase the three men would be rescued. On 17 March, Pollard and Ramsdell arrived in Valparaiso, reuniting the five men who had survived the entire ordeal. All five were Nantucketers. The only non-Nantucketers to come out alive were the three men who chose to stay on Henderson Island on 27 December 1820.

On 23 March, Chase, Nickerson, Ramsdell, and Lawrence were deemed fit enough to board the Nantucket whaler the Eagle and set sail for home. Two months later, Pollard would follow them on the Two Brothers.

On 9 April, the Surry arrived at Henderson Island. There, Chappel, Weeks, and Wright were still alive. They were in bad condition as well. Having only a single pair of pants between them and living off birds, shellfish, eggs, and berries. Water hadn’t flowed on the island since their seventeen shipmates had left.

On 11 June, the Eagle arrived on Nantucket and Chase discovered he was a father to a fourteen month old daughter, Phebe Ann. The community of Nantucket was overwhelmed. It was as if they wouldn’t believe the story unless they heard it from Pollard’s own lips. Pollard arrived on Nantucket on 5 August and confirmed the rumours.

By the time Pollard returned to the island, Chase had already begun work on his book.

By 22 November 1821, the Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex had been begun appearing in Nantucket bookshops.

***

In November 1821, Captain George Pollard, Jr would take command of the Two Brothers, the whaleship that had brought him home three months earlier. Two other Essex men world join him on that voyage: Charles Ramsdell and Thomas Nickerson.

Pollard sailed the Two Brothers around Cape Horn and out into the Japan Ground with another whaleship. Pollard was having problems steering his and didn’t know exactly where they were due to overcast skies. The ship struck something. It was the reef below them. They were being pounded to pieces by the waves. Once again, Pollard, Ramsdell, and Nickerson would find themselves in a whaleboat on the open ocean.

When they returned to Nantucket, Pollard retired from whaling. He had destroyed both the ships he’d been captain of. Though the Essex wasn’t entirely his fault, the blame still rested on him as the captain. Pollard would come Nantucket’s nightwatchman. Every year on 20 November, he would fast in memory of the men of the Essex who had died. Pollard would die in 1869.

In contrast to Pollard, Owen Chase would have success in whaling after the disaster, becoming one of Nantucket’s most successful whaling captains. But where his professional life was a success, his personal life was a mess. He would take a voyage as first mate on the Florida, returning in 1823 with two thousands barrels of oil and to find he had another daughter, Lydia. He stayed on Nantucket until after the birth of his son, William Henry. His wife, Peggy never recovered from the birth of their son, and died.

Nine months after Peggy’s death, in June 1825, Chase married again. This time his bride was Nancy Joy, the widow of his friend, Matthew, the first of the Essex men to die. Two two already had a bond through their friendship and love, respectively, for Matthew. Two weeks later, Chase would buy a house on Orange Street, known to the community as “Captain’s Row”. In early August, he would sail to New Bedford and take command of the Winslow. Chase was twenty-eight, the same age Pollard had been when he took command of the Essex. Unlike Pollard, his command would be a success.

After two successful voyages on the Winslow – though during the second one they had to return to Nantucket for repairs – Chase gained command of the as yet unbuilt Charles Carroll. It was to be one of the largest ships of the Nantucket fleet and one of the first whaleships to be built on the island.

He returned from the Charles Carroll‘s first voyage to loss, though the voyage was financially successful. Nine months after he’d left, Nancy Chase had given birth to a daughter and had died. Greeting Chase on the wharf that day were Phebe Ann, fifteen, Lydia, thirteen, William, eleven and Adeline two and a half. Adeline didn’t know either of her parents.

At forty, having married for a third time, he set off on his last whaling voyage. Sixteen months later, his wife gave birth to a son. When Chase returned in 1840, he divorced her. He knew his wife had cheated on him, having done the maths realised he’d been at sea when the child had been conceived. The divorce was granted on 7 July and Chase took custody of the boy.

He married a fourth time two months later and would stay on Nantucket for the rest of his life.

Unlike Pollard, old age was not kind to Chase. The headaches that had plagued him since the Essex became worse and he was eventually institutionalised. After that, his house was explored and a cash of food was discovered in the attic. His memories of the three months at sea in 1820-21 were coming back with force. He thought he was back there, fighting to save the lives of his men. Chase would die in 1868.

Thomas Nickerson would return to Nantucket after the wreck of the Two Brothers. Eventually, he retired from whaling life and found a position in the merchant service. He would marry, move to Brooklyn, New York and have no children. In the 1870s, he moved back to Nantucket with his wife. Instead of whaling, Nantucket was now a vacation spot and Nickerson gained a reputation for being one of the island’s best boardinghouse keepers. It was one of his guests, the writer Leon Lewis, who proposed Nickerson write a book about the disaster. Nickerson did so, and though the manuscript was lost for several decades, it was published in 1984. Nickerson died in 1883.

Benjamin Lawrence returned to Nantucket and became a captain on the whaleships the Dromo and the Huron. He would marry and have seven children. He retired from whaling in 1840 – about the same time as his old first mate – and purchased a small farm on the east end of the island. He would keep the twine circle he wove during the ordeal in the whaleboat for the rest of his life. He would die in April 1879.

Charles Ramsdell returned to Nantucket as well after the Two Brothers ran aground. He eventually became a captain in his own right, gaining control of the General Jackson. He married twice and had six children. He died in 1866.

Thomas Chappel returned to London in June 1823. He contributed to a religious tract that had every spiritual lesson from the Essex. He would die on the fever-infested island of Timor.

Seth Weeks continued as a crew member on the Surry, the ship that had taken him, Chappel and Wright from Henderson Island. The ship would take them through the Pacific, to England and back to the United States. He may have returned to Nantucket and continued whaling. Eventually, Weeks returned to Cape Cod where he was the last of the Essex survivors to die.

William Wright joined Weeks in staying on the Surry. He may have returned to Nantucket and continued whaling as well. He would return to sea and be lost in a hurricane off the West Indies.

***

Around 1840, a man on the Acushnet would meet a teenager during a gam – a meeting of two or more whaleships. The man was Herman Melville. The teenager was William Henry Chase, the eldest son of one of the premier whaling captains, having followed his father into whaling. Chase would tell Melville what had happened to his father on the Essex and give him a copy of his father’s account. Melville would use the story as the basis for his novel Moby-Dick. It would be published in October 1851.

***

I am indebted to Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea from which I have drawn nearly everything in order to write this blog post.

Advertisements Share this: