How to Win an Oscar

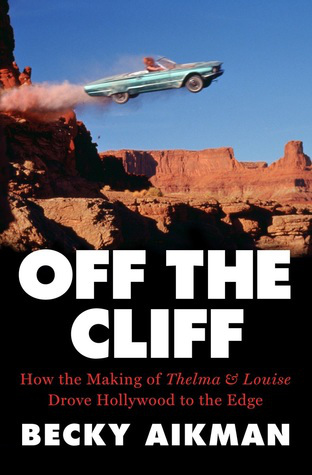

Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge

A book review by Pam Munter

It was 1989 when the filming began, in an era of violent and graphic blockbusters and a culture driven primarily by white men. In other words, a Hollywood not so different from today. Everyone expected that the revolutionary and subversive “Thelma & Louise” would shake Hollywood into a transformation, but it turned out to be a minor tremor. Becky Aikman has written a smart, insightful and creative account, not only of the making of that film, but its cultural backstory in Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge.

It was 1989 when the filming began, in an era of violent and graphic blockbusters and a culture driven primarily by white men. In other words, a Hollywood not so different from today. Everyone expected that the revolutionary and subversive “Thelma & Louise” would shake Hollywood into a transformation, but it turned out to be a minor tremor. Becky Aikman has written a smart, insightful and creative account, not only of the making of that film, but its cultural backstory in Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge.

Aikman begins by taking us on a journey through the history of women moviemakers. The heyday for women were the 1920s with Mary Pickford, Frances Marion, Anita Loos, Lois Weber and others controlling product. But from the 1930s to the 1960s there had been only two major female directors—Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino. In 1991, only four women were credited as screenwriters on the top 50 films. Last year, there were none.

The fact that screenwriting novice Callie Khouri managed to write the female buddy road movie “Thelma & Louise” and get it made is a miracle in itself, never mind that it has two violent female protagonists who (spoiler alert) meet a shocking death by their own hands. Aikman’s animated and lively writing, taken from extensive interviews and secondary material, takes us inside Khouri’s head from the idea to Oscar night. While living with two roommates and trapped in dead-end jobs, Khouri has an epiphany, “born equally of frustration, chafing intelligence and throttled talent: two women go on a crime spree…She decided to tell no one. She would start writing dialogue on a legal pad after work.”

The relationship aspect of the story came easily—it emerged from Khouri’s life but, since she had no experience making movies, she didn’t know when she was breaking the rules. The initial reactions from the powerful suits were predictably negative but it was the women who help her along the way, a consistent theme throughout this well-crafted book. And it wasn’t easy for any of them. “Women in Hollywood had to calibrate aggression with standards of femininity, ambition with diplomacy, (which) didn’t even factor in talent or skill.”

Aikman’s research and colorful, imaginative writing is so engaging that a reader does not need to have seen the film to enjoy this journey. There are many layers here, perhaps a few too many mini-biographies of those involved, but she continually returns to the seductive hook—a Cinderella story, really, about how films got made in the late 1980s.

As preparation for filming begins, we’re introduced to the stars, Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon, who are as different as the characters they play. Davis was the compliant pleaser while Sarandon took center stage wherever she went. “Geena realized she became Thelma in Susan’s presence, slavishly admiring her maternal competence. And Susan found Geena funny and loopy in a way that only some intelligence can pull off.”

Director Ridley Scott had confidence in his actors. He was not a “woman’s director,” instead placing his attention on “the look of the thing,” constructing a “visual vocabulary” that gave the audience a desolate context. Aikman writes eloquently of the director’s intent, an aspect that might slip by an audience. “Ridley inevitably packed dimension and movement into every shot, filling the frame with layers of shiny objects, surfaces that reflected light and things that moved, like rows of ceiling fans.”

The mood on the set and on location was mostly agreeable. Sarandon made her wishes known, asked for dialogue changes and often got her way. But when Scott allowed even minor improvisation, Khouri was angry. She didn’t realize that writers were seldom welcome on the set. Scott began restricting her access. “The limitation galled her, but her presence, when she showed up, galled him.” After that, the director routinely excluded her from watching the dailies and even from invitations to screenings and previews.

The last sections of the book include quotes from reviews and statements about the film’s lasting appeal. A sleeper hit, its popularity has continued to grow. “…however far-out their actions, the public recognized in them the texture and point of view of real women’s lives.” At first, audiences didn’t know how to react to the moral ambiguity of two housewives who engage in robbery, murder and suicide. In fact, there had been extensive debate at the studio among the male executives about an alternate conclusion, one more user-friendly to 1980s audience that expected happy endings.

“At special screenings…the film still plays and plays and…can still touch off a row at a dinner party and parents debate when daughters should see it for the first time.” But did it change Hollywood? The acceptable range of content mushroomed but it has taken much longer for women to approximate the clout casually enjoyed by their male colleagues.

Khouri was ultimately pleased by the film and went on to write the TV series “Nashville.” Sarandon has continued demonstrating both her prodigious acting chops and political activism. Davis’s personal story offers the most dramatic arc, morphing from a conforming charmer to a feminist activist, subsequently establishing the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media.

“Thelma & Louise” earned six Oscar nominations, among them one for Callie Khouri. She was the first woman to win Best Original Screenplay on her own in over fifty years. Aikman noted that she “bounced to the podium” when her name was read but had written her prepared thanks in pencil so they couldn’t be read under the hot lights. “Her remarks…were endearingly unpolished but from the heart.” Khouri raised her Oscar aloft and declared, “For everybody that wanted a happy ending for ‘Thelma & Louise’…this is it.”

The book is a triumph for Aikman, too, one of the most engaging written about the making of a film. It’s a welcoming read for anyone who loves the movies.

Pam Munter has authored several books including When Teens Were Keen: Freddie Stewart and The Teen Agers of Monogram. She’s a retired clinical psychologist and former performer. Her essays and short stories have appeared in The Rumpus, The Manifest-Station, The Coachella Review, Lady Literary Review, NoiseMedium, The Creative Truth, Adelaide, Litro, Angels Flight—Literary West, TreeHouse Arts, Persephone’s Daughters, Better After 50, Canyon Voices, Open Thought Vortex, Fourth and Sycamore, Nixes Mate, Scarlet Leaf Review, Cold Creek Review, Communicators League, I Come From The World, Switchback, The Legendary and others.

Share this:

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000026_00018]](/ai/011/447/11447.jpg)