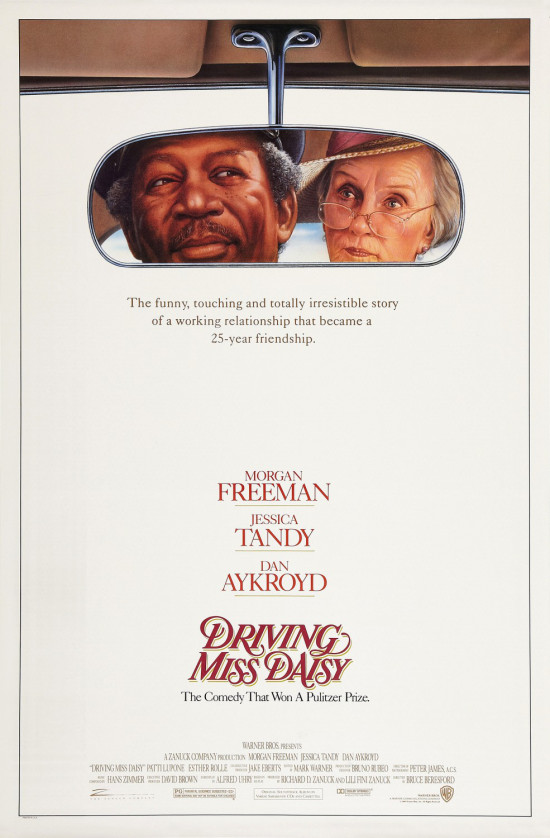

Original US release date: December 15, 1989

Production budget: $7,500,000

Worldwide gross: $145,793,296

Here I am with another classic film that I had never seen before. It’s been on my radar since . . . childhood, I guess? I’ve even retained Hans Zimmer’s memorable theme in my head throughout all of these years. For those who weren’t around when Driving Miss Daisy was released, the movie was absolutely everywhere. It was a true phenomenon that has remained in the public consciousness ever since. The visual of Jessica Tandy sitting behind Morgan Freeman in that Cadillac is a true iconic cinematic image that helped to cement the film’s permanent place in history.

Based on Alfred Uhry’s play of the same name (he also wrote the film’s screenplay), Driving Miss Daisy examines the friendship between an aging Jewish widow (Tandy) in Civil Rights-era southern America and her African-American chauffer (Freeman). Directed by Bruce Beresford (Double Jeopardy), the film won four Academy Awards at the 1990 ceremony, including Best Picture (besting, among others, another relatively recent #ThrowbackThursday subject, Born on the Fourth of July) and Best Actress for Tandy. The play also racked up many prestigious achievements, including winning the Pulitzer Prize in Drama.

So, what makes Driving Miss Daisy so resonant and enduring? Well, for starters, it nails the basics. The narrative is accessible, the characters are endearing, the cast is exceptional, the dialogue is engaging and natural, the direction is clear, and it avoids clichés. These are the hallmarks of great filmmaking and Driving Miss Daisy has them all. It’s a complete moviemaking package – a checklist with every box checked – but there’s an intangible, as well, that can’t be sculpted and can’t be predicted. It touched something in people, and that’s the main reason why it’s never gone away.

A story like Driving Miss Daisy is rife with opportunities to reach people on a deeper level. And, in its day, it succeeded handily in that realm. But it does so without using many of the common, everyday tropes that these types of films often invoke in order to illicit a desired reaction. For example, as I sat down to watch the film, I fully expected to see a story in which the chauffeur Hoke’s good nature and basic decency helped the old-fashioned Daisy overcome a deeply ingrained racism and learn that people are all people, regardless of color or ethnicity.

But, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that neither Daisy nor her son Boolie (Dan Aykroyd) ever subscribed to the racist teachings that they were undoubtedly subjected to throughout their entire lives by many around them. In fact, there is a palpable sense that both regret the way that people of color have been and are treated and looked upon and that they wish they had the power to do more on their own to help the situation. But race is barely an issue in the film, not even being addressed until the third act. That isn’t this story.

Rather, this story is one of aging and seeing one’s life slipping away. No one can fight time. Or, at least, no one can defeat time. Daisy and Hoke, from their perspectives, are divided not by race, but by wealth. Hoke gets by, but has to work for it. Daisy and Boolie have plenty of money and don’t need to worry about anything. They don’t look down at anyone, but Daisy values the independence that her lifestyle has afforded her. As she ages and her body begins to betray her, that independence proceeds to vanish before her eyes. When Boolie hires Hoke to drive his mother wherever she needs to go, she resents Hoke, not because of anything pertaining to him, personally, but because of what he represents in her own life.

But as she concedes to his usefulness and they spend more time together, their acquaintanceship blossoms into true friendship and then into a genuine bond. Hoke isn’t young, either. He’s a step behind Daisy, but both have lived full lives. Yet, as they continue to associate, they help each other see that no one is ever too old to learn something new or to gain a fresh perspective on life.

Without getting into details, I also want to take a moment to state that I was impressed that the film didn’t end in the way I expected it to or in the way that most films of this ilk would end. The film’s focus remains true to the friendship between Hoke and Daisy, right up through the finale, not allowing itself to succumb to other temptations just to shoot for those sentimentality-fueled awards. As it turned out, the film didn’t need to do that to get those awards, anyway.

Driving Miss Daisy is a simple film in several ways – certainly narratively and thematically. But its subtextual complexity lies in its desire to subvert the obvious and focus on the ideas that many would overlook when seeing the pair of Daisy and Hoke together (just like a pair of local yokel cops midway through the film). The movie is a tender look at something we can all relate to: getting older. It’s a reflection upon lives lived and a celebration of lives continuing. Tandy and Freeman are as charming now as they were in 1989, taking us on a journey that is far more profound than any that can be traveled by Cadillac.

Like us on Facebook!

Advertisements Share this: