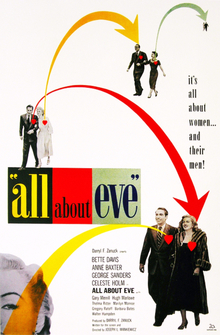

- All About Eve, Joseph L. Mankiewicz*

- Born Yesterday, George Cukor

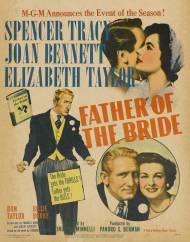

- Father of the Bride, Vincente Minnelli

- King Solomon’s Mines, Compton Bennett & Andrew Marton

- Sunset Boulevard, Billy Wilder

Once again, a dark and socially relevant Best Picture was followed by a much lighter year in which the Academy remembered that comedy films existed. Unfortunately, they were so out of practice they missed the good ones. The nominees for Best Picture in 1950 included two comedies, both moderately screwball; a Hollywood noir; and a location-shot, Technicolor adventure. None of these genres traditionally does very well at the Oscars, at least in terms of Best Picture, so the stage was set for a potentially precedent-setting year.

So it should come as no surprise that the winner was the only straight drama on the list, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve, which won him his second consecutive awards for Best Director and Best Screenplay. The film dramatizes all the ways career ambition is bad for women, and the only way for them to find true happiness is to devote themselves to their loving husbands. Such a happy and uplifting message could not go unrecognized by the Academy.

They just handed him the Oscars when he pitched the script.

They just handed him the Oscars when he pitched the script.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great movie, if somewhat dated and more than a little uncomfortable in its propagandistic intentions, but more on that next week. If I’m honest, aside from this film and Sunset Boulevard, I found 1950’s slate to be terribly, terribly weak, especially compared to the last couple of years…and it didn’t have to be. For example, if the Academy really wanted to nominate a Spencer Tracy comedy, they’d have done better to replace Father of the Bride with Adam’s Rib. Also, though it pains me to bring it up, I have to mention that The Third Man was released in the U.S. in 1950 and, unforgivably, was not nominated.

This single smirk by Welles was better than any of the Oscar-nominated performances.

This single smirk by Welles was better than any of the Oscar-nominated performances.

Oh well, what’s done is done. So without further ado, let’s have a look at the first three nominated films before getting to the ones that are, rightly, considered classics.

King Solomon’s Mines, a Technicolor adventure set and filmed in Africa, was 1950’s Trader Horn, following a naïve American traveling with a grizzled, cynical British adventurer on a mission to save a white person lost in the uncharted wilds of central Africa. It also mimics T. Horn insofar as the story pauses at least four times in favor of lingering shots of African fauna and monologues about humanity’s place in the natural order, at the expense of consistent pacing and a satisfying climax. To its credit, King Solomon’s Mines contains a hell of a lot less racism and sexism than its predecessor (though it is still there, just more subtly woven), and at least as the courtesy to fake any on-camera human deaths.

I really could just copy-paste my review of Trader Horn here, because aside from being in color, I can’t think of much that sets King Solomon’s Mines apart. I could also lift from my assessment of Gone with the Wind, in that this film earned its spot in the Best Picture nominees by being lavish, expensive, and beautifully photographed, but featured a very dull and poorly-paced story. At least GwtW had a memorable climax…King Solomon’s Mines stumbles drunkenly over the finish line with a swift narrative collapse that suggests the director received word that his car was illegally parked on Hollywood Blvd. and he had to return and move it immediately.

Naturally, he was eager to receive word about his cube.

Naturally, he was eager to receive word about his cube.

Credit where its due, though: the film does feature a strong environmentalist message, or at least strong for 1950. There are more than a few surprisingly insightful monologues by the grizzled veteran adventurer about respect for animals and the natural world, and how arrogant it is for humans to treat the Earth as nothing more than a resource for our pleasure. Unlike Trader Horn, the protagonists only kill animals when directly threatened, and every time they have to, the act genuinely affects them.

In the end, our heroes do not find, or even come close to finding, the titular mines, nor do they succeed in finding their lost white guy…but this turns out to be a blessing in disguise, since his wife falls for the aforementioned Grizzled Adventurer along the way, and by the end locating the husband would have really cramped their style.

Of course, they’ll still have to deal with his S.O. when they get back to civilization.

Of course, they’ll still have to deal with his S.O. when they get back to civilization.

The best parts of King Solomon’s Mines can be condensed into a compilation of sweeping panoramas of the east African landscape and shots of the endemic animal species. I guess I’m saying you should just watch a David Attenborough documentary instead.

Next was Born Yesterday, the earliest example I have found so far of the “smart is the new sexy” trope.

Though of course they their glasses off when it was time for romance. Smart isn’t that sexy.

Though of course they their glasses off when it was time for romance. Smart isn’t that sexy.

When I told my older sister that 1950 was a weak year, and then proceeded to mention that Born Yesterday was among the nominees, her reaction–that it’s a great movie and Judy Holliday is wonderful–has me worried that the next decade or so of this blog could lead to a real falling-out between us. She’s already upset with me over my (anticipated) conclusion that An American in Paris didn’t deserve to win in 1951, but we’ll get to that soon enough.

I mean, it’s not a bad movie by any means…I found it funny, charming, and full of great moments. I laughed a fair amount, which is the chief criterion, perhaps the only criterion, for judging something a good comedy. But still, overall, the movie fell flat. Maybe it was because I watched it only a few days after All the King’s Men, and just wasn’t emotionally prepared the sight of Broderick Crawford shouting his way through a naïve romcom with delusions of insight.

Or maybe it was the four-minute, dialogue-free scene where they sit and play gin. That’s not a joke.

Or maybe it was the four-minute, dialogue-free scene where they sit and play gin. That’s not a joke.

But I don’t think that’s the whole story. I think what really goes wrong with Born Yesterday is the fact that it tries to be more than what it is. It’s not satisfied with being a romantic comedy…it clearly has grander political and social points on its mind, and the script consistently fails to deliver.

The plot, basically, is this: millionaire junk dealer Harry Brock (Broderick Crawford, essentially playing Willie Stark in an alternate timeline) arrives in Washington, DC with the idea of “buying” a senator. He comes with his fiancée Billie (Judy Holliday), an ostensibly dumb blonde, and hires William Holden (William Holden) to teach her how to behave with class. Billie and William quickly fall in love, and he transforms her, Flowers for Algernon-like, into an intelligent person.

You can tell when it happens because she starts to wear glasses. You know, like smart people do.

Combining the one-two punch of love and intelligence, they show Brock who’s boss–by leaving him free from their meddling and with all of his money and properties…yay?–and ride off into the sunset.

Unfortunately, the film doesn’t just stop there…instead it has points to make about the American political system, and brother, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington it ain’t. It is adorably innocent even in its “cynical” moments…for instance, positing that 95% of Congress is made up of upstanding, moral, hardworking patriots, and only a “few bad apples” are vulnerable to outside interests. And even with Harry Brock written and performed as the world’s most ignorant straw man, the movie still can’t manage to demonstrate this idea convincingly.

The film’s idea of “getting serious” is having William Holden deliver several speeches about political responsibility and the importance of an educated populous, speaking of a level of participation in the political process that I don’t think America has ever had. I can’t judge the film as a simple comedy when it tries so hard to be something more, and then shits the bed so miserably every time it tries to address anything deeper than “general corruption.”

“Hm, we’d better cut to Broderick yelling at somebody. I’ve run out of Thomas Jefferson quotes.”

“Hm, we’d better cut to Broderick yelling at somebody. I’ve run out of Thomas Jefferson quotes.”

I haven’t even mentioned Billie’s “transformation” from dumb to smart, which the film’s Wikipedia article assures me happens at some point. Even in the end, when she is fully intelligent, her lines are nothing but paraphrases of William Holden and Thomas Paine, delivered with the intonation and conviction of someone reciting a list of Latin verb conjugations. However, I think Judy Holliday did a great job with what she had, and it’s a funny, if shrill, performance (though I don’t think she deserved to win Best Actress).

And even with all of that, it wasn’t the worst comedy nominated this year. That would have to be…

Father of the Bride should have been amazing…a screwball comedy about the trials and tribulations of putting on a wedding starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor, directed by Vincente Minnelli. It sure did well in 1950, and still enjoys a pretty favorable reputation…but I kind of hated it. Even at 92 minutes it seems stretched and ill-paced, and almost every joke is based on one of two tired, hackneyed stereotypes: a) men are wearied, stoic victims of emotional women, and b) women be crazy, amirite?

Fortunately, the 1950s knew how to handle the problem with dignity and class.

Fortunately, the 1950s knew how to handle the problem with dignity and class.

The “story” is told in flashback by Spencer Tracy, who from his very first line–delivered directly to camera, to “the fathers out there”–looks bored and out of place. This could have been great for his character, who is both of those things and more throughout the film, but every aspect of Tracy’s lackluster performance just screams that he took the role based on a dare.

Anyway, he plays Stanley Banks, whose daughter Kay announces her surprise engagement to some schmuck with the unlikely name of Buckley Dunstan. This comprises the entirety of the film’s first act. From then on we are treated to an hour of mishaps, misunderstandings, and tomfoolery leading to the wedding, all of which are solved with some hugs and soft words, until the movie just sort of ends. I kept waiting for the payoff for this ordeal, but the movie offers nothing…it was as rewarding as playing solitaire. In the back of a night bus. To Stockton. And the aces are missing from the deck.

Along the arduous path of clichés and instantly forgettable scenes, the movie tries to muscle in some “heartfelt” moments that are meant to remind viewers that fathers and daughters share a very special bond (see above photo) that not even marriage can destroy.

While the bond between a husband and wife remains separated by twin beds forever.

While the bond between a husband and wife remains separated by twin beds forever.

There’s only one moment in the film that was interesting, and only because it was completely different from everything that comes before and after it. It’s a short dream sequence Stanley endures on the night before the wedding, encapsulating all his fears and trepidations, and it’s actually very avant-garde and well-done. Unfortunately, it does its job too well, since it does in two minutes what the rest of the film can’t do in ninety. After watching it here, you can safely ignore the rest of the film.

I’ve seen some bad movies in this project, but this was the first one in a while whose inclusion in the list of nominees genuinely baffled me. It’s hard for me to believe that even in 1950 was this film considered anything more than a project cobbled together by bored professionals who should know better and who had an afternoon to kill. In fact, just to be sure I wasn’t missing something or being unfair to a classic, I even watched the 1991 remake of the film, to see if there were any substantive differences between a Best-Picture nominated movie starring, I must restate, Spencer goddamn Tracy and Elizabeth frigging Taylor, and a cash grab family flick starring Steve Martin–who hasn’t made a good film since the Reagan administration–and Diane Keaton.

And goddamn it, the remake is better. It’s still pretty bad, but at least the lead actor actually makes sense in the role, and it just seems to make far more sense as a light ’90s comedy. So that is the legacy of Father of the Bride: a bad film that eventually got remade as a mediocre one.

So there is the start of 1950…not promising, but as I said, it ends with two undisputed classics. And like 1934 before it, the strength of the great films compensates for the weakness of the bad ones. Part II coming soon!

Advertisements Share this: