The book I am writing at the moment is about a man in prison. As well as exploring the politics that got him there it also examines his relationship with his own body, a body become turgid and heavy after decades of prison life. As his connection to what exists outside of prison and his own past atrophies, he journeys inward, free to imaginatively roam, exploring his body as though it is a terrain. Here, he is looking at a book, at a diagram of the cross section of skin.

The page in his hand had some text and a diagram, fig 17, Cross-Section of Dermis and Epidermis. Great shafts of hair rose like tree trunks from swampy land. Sweat glands and bulbs of sebaceous oil forced up to the surface. He looked at it, a rippling forrest of dark life. He looked down at the black hairs on his own forearm, a scrambled softness there, furze, gorse, briar maybe. It did not look, he thought, like a forrest. But there is much to see in scrubland. Much furtive creeping, paths tunnelled by rabbits and small boys, litter left by lovers. He traced with a fingertip, slowly walking through that wastland growth. Until breakfast and the pint sized, welcome mug of hot tea in its insulated beaker arrived, he slowly grazed his finger up and down the boggy softness of his once strong arm.

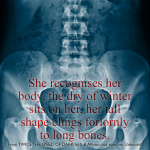

I realised as I was thinking about it that in Twice the Speed of Dark (just this very day gone to the editor, to be published by Unbound in a few months!) there is also use of the body as a terrain, a setting, in this instance, predominantly of grief. The main protagonist experiences her body and her life as being suspended, too damaged to prosper, too repaired to die. She occupies a pallid, managed equilibrium, bound by sadness, wounded by loss. The situation maintains her life just well enough for her to survive as though grief is a parasite and she is the host. She is unable to prosper, to process the loss that infects her until crisis forces a change.

Her arms feel leaden, she is burdened. She drags. She is a ghastly nurse, keeping a poisoned body just alive. A steady diet of callous harm and efficient patching up ensuring that healing or death are both impossible.

In the brilliant Catch 22, though the tone is darkly comedic, there is a character who I think informed this idea, the soldier in white, in a cast so complete that only a feeding pipe at the inside of his elbow and a waste pipe at his groin emerge from the plaster. Yossarian watches in uneasy, horrified fascination as every so often one of the brisk nurses Duckett and Cramer take the full waste bottle from one end of the soldier in white and reattach the rubber hose to the feeding tube entering at the crook of the elbow. The soldier, whoever, whatever he is, is caught in a hideous, perpetual state, a life unrecognisable. The lens we are offered in Catch 22 is bleakly, appalingly funny, but the serious implication is one of careless indifference, endless, trapped futility that mirrors the costly waging of a war that no one seems to fully understand.

It is a while since I have read William Golding’s The Spire, but as I recollect, this is another book wherein the body of the protagonist is a palimpsest, suggesting the body of the Cathedral, as it is built around what he takes to be divine inspiration but the reader can readily interpret as an altogether more earthy energy, suppressed sexual desire forced to express itself in the hubristic building of a great phallic spire.

Another book that comes to mind is Sharp Teeth by Toby Barlow. The relationship to the body might seem more simplistically straightforward as the central theme is a modern free-verse take on werewolves. But there is also nuance and shading. In an interview Barlow stated that he believed that the reason so many cultures over so many different tracts of time have told werewolf myths is because of the unique aspect of the domestic dog and its descendancy from predatory wild wolves. The dog brought the wolf to the hearth. Barlow explored the werewolf theme in a modern setting because he saw it was a fundamental way that humans have reminded themselves of their wild, uncivilised soul. The transformation occurs as the body is either forced or encouraged to express our distant, beautiful and terrifying wildness. The body is the site of a profound story.

Out of interest, (and perhaps unconsciously because I have just finished reading the beguiling Solar Bones by Mike McCormack) I searched Twice the Speed of Dark for the word bones. It appears often, as you can see in the images included with this post. If any readers would like to share their own thoughts on books that use the human body as part of their story telling, part of the manifestation of the story, I would love to get your comments and recommendations.

Share this: