“A compelling story, even if factually inaccurate, can be more emotionally compelling than a dry recitation of the truth.”

– Frank Luntz

Tax reform, tax relief, tax cuts, tax giveaways. Estate taxes, inheritance taxes, death taxes. Illegal aliens, undocumented immigrants, economic migrants, refugees, DREAMers. Pro-life, pro-choice, anti-woman, pro-murder.

Have you ever turned on the news and heard pundits on opposite sides of an argument use completely different terms to describe the exact same policy, proposal, or position? It’s a common communications strategy called “framing” and it is critical to understanding the nature of our partisan politics today and how so many issues have become utterly toxic to reasoned discussion and debate. Framing can be incredibly confusing, frustrating and, frankly, annoying. It serves to further divide people into ideological camps and confounds rational and logical discussions of the actual issues at hand, underneath all of the flowery wording. And it has been around for nearly as long as politics has.

In brief, framing theory suggests that “how something is presented to the audience (called the “frame”) influences the choices people make about how to process that information.” Generally, this means that the way an issue or topic is presented to someone, whether it is the wording that is used, the images or other media used to present the topic, or the tone or attitude in which the message is presented, directly impacts how the recipient of that information will view, process, and ultimately come to understand and hold onto that information.

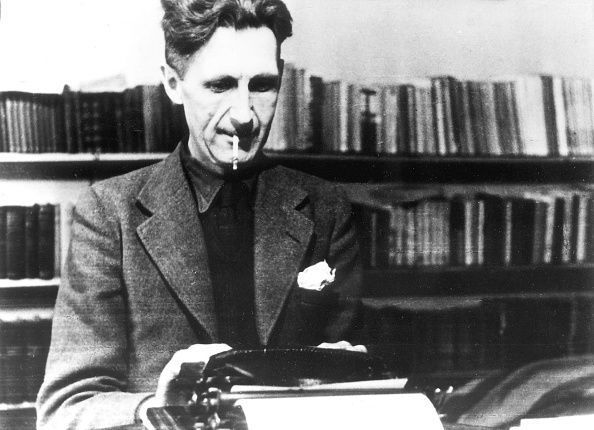

George Orwell, circa 1946

George Orwell, circa 1946

ORWELL ON LANGUAGE: THE MID 20TH CENTURY

Most people know George Orwell from his widely-read literary classics 1984 and Animal Farm, which are staples of the English-language fiction library and are commonly taught in American high-school and college classrooms. These novels are beautifully-written allegories for reality, and focus on dystopian futures and the disastrous results of Communism, and both stand up well to the test of time. These works, for anyone who has read them, clearly tell political stories and deal with many contentious topics, not least of which are the complexities of speech, language, and word choice in the realm of government, news and information, and partisan debate. As much as 1984 and Animal Farm delve into the questions of language and word use in a political context, Orwell has a far more important work that is much more straightforward in addressing this critical issue: his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language.

Politics and the English Language was published in the April 1946 issue of the journal Horizon, during a time when Orwell was writing prolifically after his wife’s passing, often on the topics of truth, use of language, and politics. The essay received both criticism and praise at the time of its publication, but in the decades since it has been widely seen as prescient. The essay focuses its criticism on the poor use of language, especially to confuse or to obfuscate the truth of one’s intentions or the point one is trying to get across. He discusses how words can be misused so often that they become entirely meaningless, which is most definitely a problem that has not disappeared from the arena since his writing. In one passage that could have seemingly been written in 2017, Orwell argues:

“The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’. The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice, have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of régime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.”

Orwell continues by detailing how complex, fancifully-structured language can often be hiding falsehoods or outright lies. He states, “The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish squirting out ink.” Orwell most definitely was not a fan of overused idioms and clichéd metaphors, and goes after many of the most commonly used throughout the essay. Some of the metaphors he latches onto are a bit outdated today, but many are still trotted out by major media on a routine basis: toe the line, play into the hands of, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed, and no axe to grind, for example.

Still, his harshest polemics are reserved for politicians, saying “All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.” He continues to tear apart political language and those who (mis)use it, maligning most political speeches and writings as having a “lifeless, imitative style” and rarely, if ever, having “a fresh, vivid, home-made turn of speech.” He excoriates politicians giving prepared speeches as “tired hack[s]…mechanically repeating the same phrases,” and compares them to automatons and those uttering repetitive responses in church. His harshest criticism is perhaps what strikes me as the most applicable to the modern age and although referencing events of his day, the passage reveals the intrinsic truth of political language in any time and place:

“In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements. Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

If George Orwell was a crusader for simpler, easier-to-understand language in politics, he absolutely would have despised the man who I will introduce next, the influential GOP pollster and focus group fanatic Frank Luntz.

Frank Luntz on Fox News. Image courtesy of TheBlaze.

Frank Luntz on Fox News. Image courtesy of TheBlaze.

FOCUS ON FRANK: FRAMING FROM 1980 – 2000s

Climate change. Death tax. Energy exploration. Government takeover. Contract with America.

If you’ve ever heard any of those phrases used before – and I can almost guarantee you have if you’ve been alive and alert sometime within the past 30 years – you have been exposed to a work of Frank Luntz framing genius. Luntz, born in Connecticut in 1962, has been the most influential Republican pollster and linguistic wunderkind of the modern political era. His work with wording has altered the way Americans and people across the globe think of concepts as diverse as energy, taxation, climate, healthcare, education, and more. Luntz’s efforts on behalf of conservative candidates and causes have helped not only reorient the lenses through which we view many of the most contentious issues of modern times, but also has changed the methods by which political parties, candidates, and organizations collect and process opinion data from the public at large.

In the latter half of the 20th Century, particularly beginning in the 1980s, political framing itself became a topic of discussion in the news, particularly for the nascent 24-hour cable news industry. The terms ‘spin’ and ‘spin doctor’ became entrenched in the American lexicon as words for political framing and the operatives who were in charge of said framing. Spin became the story itself, even more so than the actual policies, politics, or candidates engaged in running for office. As CBS News host John Dickerson writes in his must-read campaign book Whistlestop, “One analysis of debate night coverage in 1988, relative to the campaigns that had preceded it, showed a significant increase in the amount of attention paid not to what the campaign was actually doing, but to the spin the campaign was emitting to put the best gloss on what was happening.” As spin became more and more a focus of coverage, it became more and more important to have a master spin doctor on your team. And nobody was better than Frank Luntz.

As the 1980s flowed into the 1990s and Bill Clinton was elected President in 1992, the GOP seemed to be at a nadir. It was time for Luntz to get to work. He explicitly credits Clinton for his great successes, saying, “Bill Clinton made Frank Luntz because Bill Clinton discovered the power and the influence of words.” During the 1994 Congressional election campaign, Luntz was hired as a pollster for the Republican party, and was asked to give a presentation at a GOP retreat in Maryland. At this retreat, he discussed how “the American people didn’t trust politicians in general and, quite frankly, didn’t trust Republicans in particular,” which led to Luntz’s proposal of a “proclamation”, altered by then-Congressman Newt Gingrich into a “contract”. This proposal became the famous ‘Contract with America’, which rocketed the GOP to control of the House and Senate for the first time since 1953 and elevated Gingrich himself to the lofty perch of Speaker of the House. Luntz was crucial to the framing of the Contract, making sure that key aspects were added or retained; these include a section stating “Keep this page to hold us accountable,” which according to Luntz did not exist in the original document, as well as a statement to the effect of “If we break this contract, throw us out. We mean it.” These additions were incredibly important to framing the document as a contract, which signifies more than only a campaign statement; it is a hard copy of one’s sworn word and connotes a firmer resolve than a simple promise. These words, “accountable”, “contract”, “break”, all are related to contractual obligations and put the voter in the contractual frame instead of the typical campaign frame; Luntz himself describes them as “enforcement clause[s]”, and says that they are “what told people this was for real.”

After the unparalleled success of the 1994 election, Luntz went on to continue working with conservative candidates and causes throughout the US and the rest of the world. He notably coined the terms ‘climate change’ and ‘death tax’ in reference to global warming and estate taxes, respectively. I will address those topics in further detail in the coming sequels to this story. His path has included stints working with the George W Bush White House, a wide range of corporate clients, the Israeli government, the UK Conservative Party, and many television networks as an analyst to give focus group perspectives, particularly after political debates. In many ways, our current political world has been shaped by the work and the words of Frank Luntz.

In the next piece in this series, you will begin to understand just how much framing can impact rational discussion of policies, can obfuscate what is really going on, and see how language can be intentionally used to deceive. And although Frank Luntz is fond of saying things like “facts matter” and “credibility is more important than anything,” we’ll see just how far he and other master framers have been willing to stretch language in the pursuit of political gain. In the words of George Orwell, “Political language – and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists – is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

Share this: