The lies contained in conventional historical narrative sometimes carry a peculiar, irrational sting.

The lies contained in conventional historical narrative sometimes carry a peculiar, irrational sting.

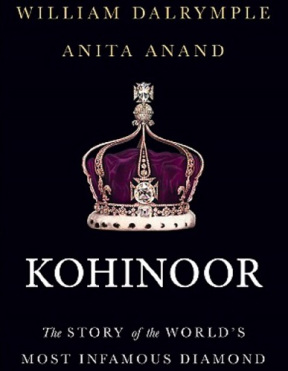

Take the Koh-i-noor Diamond, currently part of the British crown jewels. A Smithsonian article by Lorraine Boissoneault examines its history and reviews a book about it, Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond by historians Anita Anand and William Dalrymple.

I had to read this book, because I remember seeing the thing itself, in an exhibit at the Tower of London back in the 1980’s. And I remember how seeing it made me feel a little ill. It was part of a whole lot of purloined goods. Instinctively, I knew that everything in the interpretive text was a lie. I knew that, even though I hadn’t quite formed the words to say so at the time.

“A gift from the people of India?” You’re kidding me! It was nothing of the sort. It had been taken off the hands of a ten-year old prince, sole heir to a kingdom in India–along with the rest of the kingdom, naturally. Ten years old. We don’t know how things would have turned out if he’d been allowed to grow into his ancestral role. He wasn’t exactly a gentlemanly role-model or anything like that. For now he lies buried in England. But he was just a child, and all of Empire was aligned against him.

Anand and Dalrymple take readers through the dramatic, poisoned history of the diamond, which can as well be read as a history of the subcontinent itself. The Kohinoor played, they say, a cameo role in that history, elusive and not as sparkling as you might think. Everyone wants it, the East India Company included. And here’s the thing, of all the kings and merchants, soldiers and courtiers who coveted it over the centuries, no one’s hands are really clean. As for the thing itself, it ends up cut down to half its size, around Queen Victoria’s neck.

The book leaves us with the question: what do we do with these stolen artifacts from the colonial era? What should we do with them in the real world and in our minds? Let’s be real. The likelihood of the diamond’s return to the land of the riverbed that gave it up is nonexistent. Still, the book makes us probe the questions related to that possibility: To whom might one return the diamond, since the king who last owned it was deposed and is now dead and the kingdom itself no longer exists?

Perhaps a clear sign by the museum case is an option, a sign that does not disingenuously gloss over the historical facts. Three decades ago, when I came to set my tourist’s eyes on the fat, glassy gem, and felt a sudden pang at being lied to, I think a clear sign would have gone a long way for me.

Share this: