DIANE DE BEER

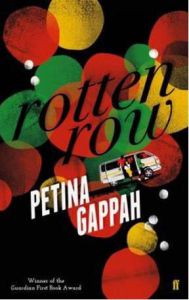

Petina Gappah: Rotten Row (Faber & Faber):

This is her Petina Gappah’s third book. The other two titled An Elegy for Easterly, her debut and also short stories like this latest one, followed by The Book of Memory, her first novel which tells the story of a woman incarcerated in a very harsh (are there any that aren’t?) prison in Zimbabwe.

This is her Petina Gappah’s third book. The other two titled An Elegy for Easterly, her debut and also short stories like this latest one, followed by The Book of Memory, her first novel which tells the story of a woman incarcerated in a very harsh (are there any that aren’t?) prison in Zimbabwe.

The titles alone would have turned my head, but with this author, it is where she comes from and her writing that grabs you. Why would we not want to read about a neighboring country from someone who has found a unique way of telling her stories and speaking her mind.

Just some bio: She is a Zimbabwean who works as an international lawyer in Geneva and while she doesn’t want to be defined as a specific writer for anyone, she is telling stories about her people and her land. She doesn’t live there full time anymore, but she returns to write and it is obvious in her writing where her heart lies.

It is her extraordinary insight, her obvious fascination with human beings and what they do, her protective nature of her country and its people and the way she shows us their lives that is so appealing. With so many people from across our border working in our country, one has to wonder about their lives back home, how it feels to have to leave your homeland for different reasons but with the same outcomes, and what hope exists to one day return to a country that is home?

She gives us an inkling of that; The life in the ordinary lives of people trying to function in an abnormal situation. Sound familiar?

She introduces the title of this latest book thus: “It is a street redolent with remembrance.” It represents the start of colonialism in that country, but also houses the headquarters of ZANU PF yet the place that most people think of when they hear the name Rotten Row , is the criminal courts. It is all these elements that permeate her stories that are linked by a certain humanity that is a part and party to every life she tells of.

Gappah allows her writing and her stories to show what she doesn’t necessarily want to scream about. In that way, the impact on everyday lives, how people survive, what they have to do to simply get the ordinary done, also shapes her world and the one she wants us to understand.

It’s not about hardship, it’s about life and from Gappah’s point of view, it is always filled with laughter. She knows that this will keep us moving on as we start understanding each other, see one another and view people in a very different light – without judgement.

She is so obviously from this continent, and there’s a writing that bristles with her own sense of place and who she is. And probably because she has distance, it is the sharpness of her gaze that catches the reader unawares.

The following three books all deal with race but with such an individual perspective, it’s compulsive reading. It’s as if individuals have suddenly found a voice and a way of telling their own stories. Perhaps this is a time when it is simply too painful not to speak:

Paul Beatty: The Sellout (One World):

Not knowing much about this book but that it is listed as the Man Booker Prize winner of 2016, I wasn’t too keen to read a novel about modern day slavery, not reports as we see on the news daily, but fiction.

Not knowing much about this book but that it is listed as the Man Booker Prize winner of 2016, I wasn’t too keen to read a novel about modern day slavery, not reports as we see on the news daily, but fiction.

It was only when starting to read and encountering Beatty’s evil sense of humour and the approach he has taken to telling a very specific race story, that my hesitation turned into delight.

I’m not the laugh out loud kind of person even when I think something is funny, but with this one I couldn’t contain the laughter.

Writing about a slave called Hominy, his master tells of the slave’s movie bio: “…from the ages of eight to eighty, including most notably Black Beauty – Stable Boy (uncredited), War of the Worlds – Paper Boy (uncredited), Captain Blood – Cabin Boy (uncredited), Charlie Chan Joins the Klan – Bus Boy (uncredited). Every film shot in Los Angeles between 1937 and 1964 – Shoeshine Boy (uncredited) Other credits include various roles as Messenger Boy, Bell Boy, Buss Boy, Pin Boy, Pool Boy, House Boy Box Boy, Copy Boy, Delivery Boy, Boy Toy (stag film). Errand Boy and token Aerospace Engineer Boy in the Academy Award-winning film Apollo 123.

It’s this kind of writing, showing how it is done, bringing in real names and real incidents that keeps you racing through this one with enthusiasm. We live in such different worlds, where we are born, what colour or race we are, our class designation, that often, we are impervious to the needs or wants of others. Entitlement encourages many to misunderstand the lives of others. How can you know if you’ve never been in that place, never been aware that it even exists. With our past, we know that when the other is hidden, it is easiest to ignore.

That is what Beatty has done so successfully but with such flair. He is determined to put it all out there but in such a way that while it hits you over the head, it is so cleverly done you are sucked in.

Very few reviews don’t use the word brutal, and that’s true. But then that’s the subject he is dealing with. It’s the year 2017 and we’re still talking about the basics of race here. It is about time that human beings start telling their own stories and tell it the way they want to get it out there.

Paul Beatty has decided to do it with hysterical laughter and he does it magnificently. In the end, when all the noise is silenced, it is excruciatingly entertaining and painfully funny.

How can it not be? And how can anyone resist?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The Sympathizer (Grove Press):

Think about the Vietnam War and the stories that have emerged following the American participation and their final withdrawal.

Think about the Vietnam War and the stories that have emerged following the American participation and their final withdrawal.

It’s exactly those stories, told from the vanquished’s point of view while shaping the narrative that compelled this Vietnamese-American writer to come from the victor’s vantage, a story he believed had never been told, not from this particular point.

The narrator is a communist double agent which in the Vietnam scenario already plays all the odds. He is a man “of two minds” says the blurb, “a half-French, half-Vietnamese army captain who arranges to come to America after the fall of Saigon and while building a new life with other Vietnamese refugees in Los Angeles is secretly reporting back to his communist superiors in Vietnam”.

Well that’s the gist of it but of course, there’s much more to this particular story which romps through the American post-war landscape from a chillingly cynical point of view – but one that knows from experience.

One of the devices he uses to expose the way refugees, their lives and their countries are dealt with is to have the narrator act as an adviser on an American film on the Vietnam War. Without naming the film, he picks the one that’s most memorable if you think back to your own experience of the big movie experience of that particular war.

It’s the way he tells the story, the way there are many different hooks that hitch a ride in the contemporary world. Think refugees for example. Nothing has changed from the days that the Japanese were interned during WW2 – and before of course.

Why would the (western) world suddenly react differently. In their world nothing has changed except this horror of people whose lives are being threatened trying to find safe havens. We’ve been there before many times.

It’s as if suddenly people have found a voice, a way of speaking about prejudice and the way they and their people have been trteated without shame for ever.

But the real key to these voices is the way the stories are told. It’s not a guilt trip per se. It’s telling a story with such hilarious fanfare that one cannot resist the ride. The writing is superb, the story opens new windows, has you thinking and understanding in a different way or simply reminds one that everyone is not treated the same in this world not even or especially not in the US of A.

It is a story that needed to be told and one you want to read especially in this world today where we need to turn towards rather than away from one another.

It might not sound that way, but it’s a fun read – and then it flips your world.

Colson Whitehead: The Underground Railroad (Fleet):

It’s the kind of book that has similar impact to Tarantino’s Django, he could get away with what he was doing because of who he was, what he had done before and because it was a movie.

It’s the kind of book that has similar impact to Tarantino’s Django, he could get away with what he was doing because of who he was, what he had done before and because it was a movie.

It feels as if this novel has also found a new voice, a way of telling the slavery story which is familiar but would make people stop and listen to this particular tale. It might feel like it’s not real, what with an underground railroad (almost Harry Potter-style) that mysteriously disappears and has guards watching out for it and allowing slaves to vanish into a world where they couldn’t be found.

But that’s what it took. How could you get away in a world that belongs to those who are keeping you in chains, where their punishment is the only way that wrongdoing is treated and where their laws are applied in the way that suits them.

Think about living on the other side of that protected curtain or perhaps you do. It is the thought of losing that protection that so many strange things like Brexit and Trump are happening , but that’s a different story.

The way we look at the past is what fashions our future yetmany haven’t been given that right, and it has resulted in enslavement for future generations as well. It is those who have been victimised who have to keep telling their stories the way they want to.

And this is exactly what Whitehead has done here. He has imagined a story that allows him to capture all the horror of his people in the past, and he has in this way inhabited his history in way that unfolds a unique perspective on the past.

As Cora, a slave on a cotton plantation in Georgia dreams of escape as her mother has done before her, she also battles with the way she was discarded by the one who should have protected her. But then she hears about the Underground Railroad, and she knows it is her time to run.

It is a thriller in the real sense of the word, but one is constantly reminded and Whitehead never lets his reader off the hook, that we are dealing in reality here and one that has reverberating repercussions in the contemporary world which is there daily for us all to witness.

It’s brilliantly written, draws you completely into the story but also reminds us like a drumbeat that all things aren’t equal – not in this world – never.

Tim Winton: The Turning (Picador):

A few years back, I placed a few Tim Winton books on my bookshelves because I could only manage urgent reading of books that had to be reviewed and could not find the time for these particular books in-between. I knew I wanted to read them but they would have to wait.

A few years back, I placed a few Tim Winton books on my bookshelves because I could only manage urgent reading of books that had to be reviewed and could not find the time for these particular books in-between. I knew I wanted to read them but they would have to wait.

What was more dire at the particular time probably local books (from here and the continent) which I’m always partial to and often needs being talked about more than their international counterparts.

With the Hay Book Festival featured on DStv’s BBC World recently, Winton popped up as one of the featured authors and my interest was tweaked – also reminding me of the three Winton titles on my shelf. Described as a literary Aussie writer, his story was intriguing. The son of a copper, in fact a traffic cop who dealt mainly in accidents, Winton describes his childhood home as happy and warm but with a strong dose of trauma. This has obviously influenced his work.

I selected The Turning as my first dip into this writer’s storytelling, a collection of short stories yet strongly bound together by particular milieu, characters popping up in more than one tale and a strong sense of place.

This is a mainly white, working class, mostly small town world with the sea as a strong backdrop. There’s a feeling of characters trying to find their place in the world, sometimes turning their back but as often, turning their lives into something quite unexpected.

Almost more than the storytelling itself, it is the way Winton writes that makes you both wince at and wallow in the lives of others. It is recognisable but more importantly, there’s something addictive, almost mesmerising, about someone painting people and their place, both physically and emotionally, in such a discerning and detailed fashion.

The language is seamless yet completely from a novel place as Winton uses everything around him to sketch his characters in full colour. None of the subject matter appealed to me in particular and the book is probably more masculine than feminine or even neutral in nature. Yet, I couldn’t stop reading and it was the kind of book I wanted to pass on to everyone simply because it was such an entrancing read.

Bring on more Winton, both those on my shelf and more. And at the Hay Festival he was talking about his latest book, a kind of memoir (The Boy Behind The Curtain), which is a no brainer.

You like the writing, why would you not get to know the man?

Share this: