Day 12: Live update – Odometer 19125km. Salt lakes are a common feature within the vastly arid interior of South Australia. Half regretting the decision not to take the Oodnadatta Track back towards NSW (which meant unsealed trails, something that I am not that keen on doing for the rest of this trip as my body is massively fatigued), where I could have visited Lake Eyre, but this will do for now.

Day 12 at Pimba, South Australia.

Day 12 at Pimba, South Australia.

Rookie mistake #12: Searching for a campsite at night without prior research. It’s difficult enough to be riding all day. Attempting find and set up a sleeping space in the dark makes it worse.

Spontaneity is all well and good when you know your boundaries. Usually when it comes to travelling as a tourist, no matter which location you head to, you have a set plan in mind of where to stay, what you can eat and how you can spend your time during your stay in town. No matter how brief your plan, there is a belief that there will generally be a plan B when things don’t turn out the way that you would expect. There’s always a second place for accommodation, another restaurant or food outlet to visit, a different tourist trap to spend time, right?

Down to my final food supplies. Muesli and vitamins.

Down to my final food supplies. Muesli and vitamins.

18881km on the odometer.

18881km on the odometer.

The sunrise after a chilly night.

The sunrise after a chilly night.

Glendambo Roadhouse. Filling up on fuel.

Glendambo Roadhouse. Filling up on fuel.

It is not quite the same when you’re in the outback, or even the country areas of Australia, where you actually have to expect for the worst. Australia’s population is highly urbanised, with over 50% of its population living in just three state capital cities, which includes Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, and an overwhelming majority of people living in coastal towns. With 75% of it consisting of semi-arid or arid, the interior of Australia is one of the most sparsely populated regions in the world.

A desert landscape. Like a tiny Lego figurine, I stand in the middle of a dried up dam.

A desert landscape. Like a tiny Lego figurine, I stand in the middle of a dried up dam.

Due to isolation, the remote parts of Australia are like stepping into a time warp, where quality of amenities are often below the standard of its urban counterparts. There isn’t any incentive to develop anything more fancy than the utmost basic of facilities, so reliable venues can be difficult to find, although the main interstate highways in the outback are mostly well equipped to serve travellers on the road. However, even if amenities are available, it is not guaranteed that you will find what you actually need. Not all places have potable water, and not all servos actually supply anything upwards of 91 RON petrol. Similarly, not all camp sites should be expected to have everything you expect for a peaceful night’s sleep. They are more than just patches of grass or dirt; they’re not all the same.

The majority of my road trips have seen late nights on the road. This has much to do with the inevitability as a result of needing to cover large distances within a day, rather than the desire to ride a motorcycle through the most dangerous, riskiest time frame of a day. My day, or night as we should put it, would end either when I have located an appropriate camp site or when I simply could not continue to ride for any further due to outright fatigue, as witnessed in Day 7 of this trip.

A salt lake near Pimba, South Australia, adjacent to the Stuart Highway.

A salt lake near Pimba, South Australia, adjacent to the Stuart Highway.

Getting ready for a shower.

Getting ready for a shower.

Filling up on carbs before hitting the road again.

Filling up on carbs before hitting the road again.

Less than one fuel tank worth of riding left til I reach the next major town.

Less than one fuel tank worth of riding left til I reach the next major town.

The seemingly boundless straights of Stuart Highway.

The seemingly boundless straights of Stuart Highway.

Attempting to set up camp late at night is one of the worst decisions that a traveller can make whilst going in between major destinations. Trying to find everything that you need in pitch black darkness makes everything more tedious than it should be. The ease of any sort of night time activities is directly proportionate to the amount of lighting you have with you. After all, you want to be able to actually see where you are going.

Camp novices often assume that a burning campfire can be their central lighting source, but it can’t be relied on as a guarantee at all. The romance of a vibrant campfire and a glowing full moon is an illusion that quickly fades away when you’re not prepared in a foreign environment, as a sustainable fire requires time and plenty of prior preparation. It is crucial to have proper battery-powered lighting equipment with you when going on an adventure that likely will challenge the effectiveness of every single resource that you have at hand. When things don’t work out the way you originally wanted, you can never have too much lighting at night.

Sunset on the Stuart Highway, 50km north of Port Augusta.

Sunset on the Stuart Highway, 50km north of Port Augusta.

There’s also the issue with actually being at a campsite that is appropriate for you. Is there any space for you? Is it a safe place? Are you even aware of what is around you? As seen in one of my past adventures on the Panigale, I once pitched a tent near the vicinity of a crocodile habitat in Halls Creek, in Western Australia. I had set up my camp at around midnight, and there’s only so much you can do to fully know your surrounding environment without the guidance of penetrating daylight, especially when your only light source is a wimpy little head-mounted LED lamp. It wasn’t until next morning that I could explore the whole campsite area and understand its geography much better than before. Nonetheless, I was glad that none of my limbs were in jeopardy, and lived to ride for another day on the road.

Officially no longer in the outback as I proceed from Port Augusta to Orroroo.

Officially no longer in the outback as I proceed from Port Augusta to Orroroo.

Definitely feeling more like south-east Australia with its cooler evenings.

Definitely feeling more like south-east Australia with its cooler evenings.

A government building in Orroroo.

A government building in Orroroo.

A small break, wondering where I could find the closest camp site.

A small break, wondering where I could find the closest camp site.

Starting up a campfire in the darkness.

Starting up a campfire in the darkness.

After setting up your camp site, the campfire can then be considered into the night’s equation. Temperatures can drop to surprising lows in parts of the outback. As a tent camper, a campfire is of great significance especially during the winter seasons. The overnight sleep is a particular concern that I always have because, apart from the sleeping bag, I do not carry a padding or lining of any sort on the surface on which I sleep in the tent. I cope with such conditions by digging a square metre area of dirt and burying a heap of the ashes of used up firewood, then covering them with around 10cm of dirt. Pitching your tent over this area will ensure that you keep warm overnight, the heat of the ashes warming up the floor throughout the night.

There’s never been a camp night as a solo traveller in which I could legitimately claim as the ideal night in a tent. Time constraints, and the relative lack of sleeping equipment mean that I am required to take a dose of concrete and persevere with each night to varying degrees depending on the scenario. On the other hand, the impromptu nature of my journeys have meant that I’ve had to be flexible and creative with everything that I do. My favourite part about travelling in the outback is that the desolation encourages you to be a practical thinker and improvise things on the spot, which I believe is the very essence of adventure. All these challenges make my experiences all the better for myself!

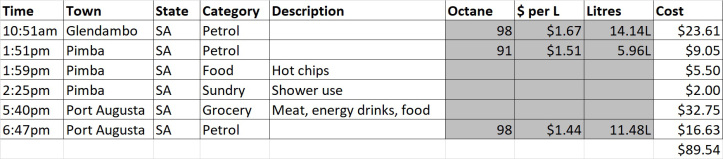

Basic Statistics for the day:

- Route: Glendambo, Pimba, Port Augusta, Orroroo, Peterborough

- Total distance: 650km

- Range of temperature: 12°C to 26°C

Expenses for the day:

General map route: