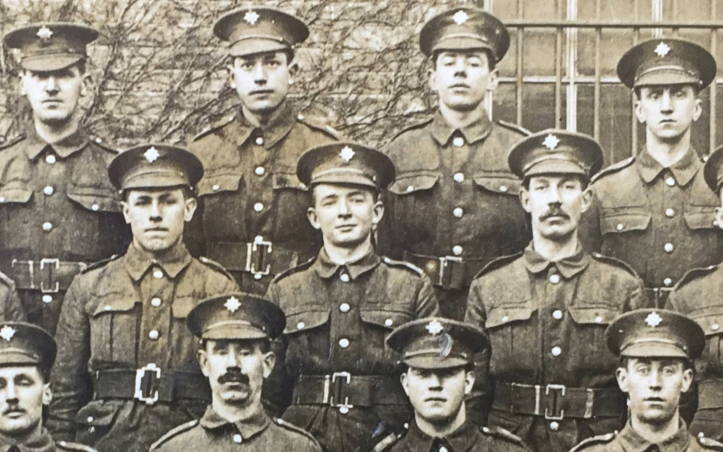

‘… [N]or the years condemn’ – Private Greg Hoban, 2nd Batt. Irish Guards, photographed in uniform in February 1917 when he was still only 17 years of age. Photo: Mick Hoban.11 November 2017

‘… [N]or the years condemn’ – Private Greg Hoban, 2nd Batt. Irish Guards, photographed in uniform in February 1917 when he was still only 17 years of age. Photo: Mick Hoban.11 November 2017

Today, on Armistice Day, Greg Denieffe writes:

Saturdays are sacred in our house; they are the perfect idyll between life’s obligations. Sundays can compete to a point but eventually, usually just after the day’s main meal, thoughts turn to the week ahead. In truth, it’s the working/school week that make Saturdays special. And, so it was on Saturday 16 September. Workwise, it was a hectic month for me, but the previous Saturday I managed to research and write up a tribute to my grand-uncle, Greg Hoban, that HTBS editor Göran Buckhorn had kindly agreed to publish on the centenary of Greg’s death. This particular Saturday, I had time to kill: I was not paying much attention to social media, just watching a game of rugby on TV, enjoying a craft beer and a steak supper. As my two girls enjoyed their TV programmes and an ice cream, I settled in to a period of “manly” washing up to a soundtrack supplied by Planxty. Monday was a long time away; later that evening I was going to tune in Up For the Match and I was looking forward to the following day: for many it would be the highlight of the Irish sporting calendar, the day of the Dublin v Mayo All-Ireland Football Final. It was a near perfect day but I was not expecting it to live long in my memory. How wrong I was.

Eleven o’clock had just ticked by and my internet feed had shut down for an advert break. I picked up my phone and saw for the first time the face of Greg Hoban. It was the face of a 17-year-old boy who within seven months of this photograph being taken would be dead. I wasn’t expecting it and could scarcely believe my eyes. I had thought of him so many times over the years. I knew my father had too, and I knew my brother, Michael, had a special interest in him but none of us had ever seen his likeness and yet, there he was looking back at me. I noticed straight away that I have his ears, I also have his eyes but I don’t have his bravery; I felt very humble and strangely emotional and I was proud that my gut instinct to mark his death had paid off. I was even more proud that I was not alone in this act of remembrance. The photograph came to me via my Lancashire-based second cousin Mick Hoban, who had begun researching our shared grand-uncle as far back as Christmas 2010. On that fateful Saturday, Mick Hoban was not only remembering Greg, he was in Ypres paying his respects and tracing Greg’s last hours.

I often remark that ‘there is a song for every occasion’ but I surprised myself in remembering that Tom Waits managed to squeeze ‘Saturday night’, ‘telephone’ and ‘second cousin’ into one and a what brilliant one. Perhaps I was (Looking for) The Heart of Saturday Night and Mick, (and Tom Waits) helped me find it.

As I have mentioned before in HTBS articles, there was no conscription in Ireland. Young Irish men still joined up by their thousands: for the adventure, for the money, to avenge the Lusitania, to avenge Little Belgium, to escape their small town. Recruitment Sergeants worked hard to fill the ranks and posters targeted every walk of life. You didn’t have to be a natural soldier to feel the pull: a relative home on leave having a quite word about the pleasures behind the line might be enough, the vicar or priest “calling you out” would sway you more than your protective parents, trying to impress a young lady with bravado or even the feeling that you had to do your bit. Some even believed that Home Rule for Ireland would be advanced by their actions. As Rupert Brooke said on the outbreak of the war: ‘It will be Hell to be in it; and Hell to be out of it’.

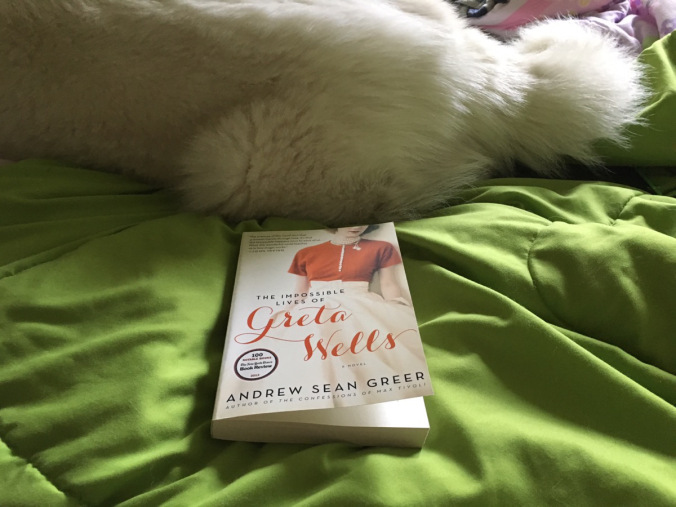

The 1911 census of Ireland shows Gregory Hoban aged 12, living with his brother Andrew aged 14, and mother Ellen, a 55-year-old widow. Ellen worked their small farm in the townland of Earlsbog Commons on the outskirts of Gowran. Greg’s occupation on his enlistment form signed on 22 November 1916, his Short Service (For the Duration of the War), gives his trade as ‘Farm Labourer’.

‘They sit no more at familiar tables of home’.

‘They sit no more at familiar tables of home’.

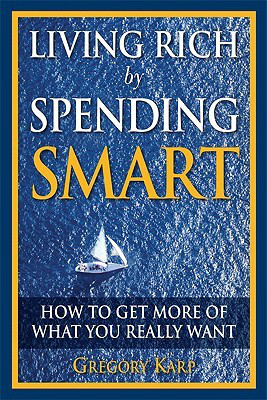

‘They went with songs to the battle, they were young’. A 1916 recruitment poster specifically aimed at the “Farmers of Ireland”. Despite farming being a ‘reserved occupation’ both Andrew and Greg were accepted in to the Irish Guards.

‘They went with songs to the battle, they were young’. A 1916 recruitment poster specifically aimed at the “Farmers of Ireland”. Despite farming being a ‘reserved occupation’ both Andrew and Greg were accepted in to the Irish Guards.

My earlier piece, posted on Greg’s anniversary covered what I was told by my dad and what I could find out on the internet. As Saturday evening passed religiously on its course towards Sunday, the comments and the messages coming my way via HTBS and Facebook were left unread. Fate is a strange thing; normally I would be alive to these but on this occasion, being content with day and nursing a nightcap, I had overlooked checking my phone until bedtime and then they reached me. David Eagleman, the neuroscientist is quoted as saying ‘There are three deaths. The first is when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time’. I was keeping Greg Hoban’s memory alive, so was Mick Hoban and so were my brother and another cousin Eleanor Doyle.

The following is an extract from Mick’s research:

My father, Andrew Hoban, was born on 26 March 1926. A year later his sister Ellie was born on 25 February 1927; 18 months later Gregory was born on 7 August 1928. Their parents were Andrew Hoban (15 June 1898 – 14 June 1975) and Mary Hoban – nee O’Neill (12 August 1888 – dd February 1969).

All I’d known about my grandparents was that they had children late in life (Mary being 37 when my father was born), that Andrew had suffered in the Great War and also had the trauma of losing his brother Gregory to that conflict. Like a lot of people of that generation, he never talked about what he’d seen in the war, but my father used to tell me of the nights when he’d be awoken by his father’s anguished screams as he relived the horrors in his dreams.

There was also the fact that not only did no one seem to know what happened to Gregory, but also that family legend had it that he’d lied about his age and enlisted into the Army before he was 18 (Indeed I had heard that he was actually only 16). He had no grave, no date of death, not even where he fought and died. It was not until Christmas 2010 that I was talking once again with my father about this as there had been announcements about how the country was going to stage remembrance acts during 2014 – 2018 to mark 100 years of the Great War.

With the aid of the internet, I decided I had to find out Gregory’s story.

Mick then went through the same process that I had carried out and eventually he gathered all the information that I included in my original article as well as the detailed report of the fighting around Ney Farm on the day that Greg was killed. Like Mick, my main source of this information was the Rudyard Kipling book The Irish Guards in the Great War. However, Mick obtained this information directly from the archivist of the Irish Guards, Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London, from whom he had applied for a copy of Greg’s record of service.

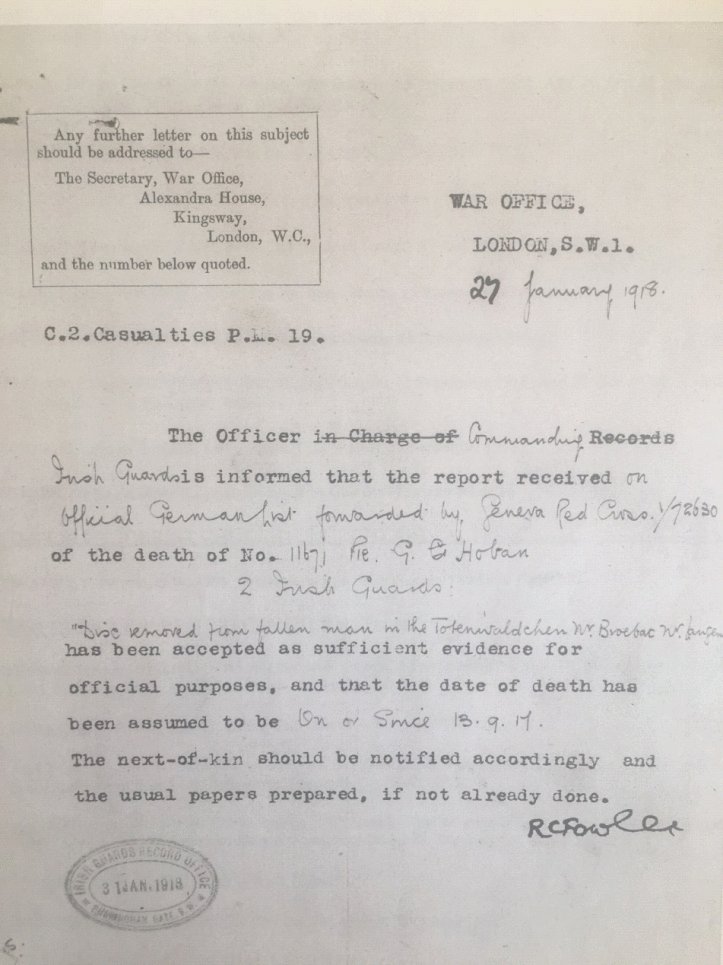

In the envelope sent by the archivist were photocopies of everything that they had recorded for Private Gregory Hoban. Included was a copy of a letter from the War Office dated 27 January 1918 which confirmed the news that everyone was expecting since Greg had gone missing, four months earlier, on 13 September 1917.

The Casualty Report confirmed that his Regimental Disc had been removed by a German soldier ‘in the Totenwäldchen, Nr. the Broebac, Nr. Langemar’ and ‘has been accepted as sufficient evidence’ of Greg’s death. The report was based on information received ‘on official German List forwarded by Geneva Red Cross’.

‘Fallen in the cause of the free’. Whilst some may find this letter disturbing, I find this act of humanity between combatants comforting.

‘Fallen in the cause of the free’. Whilst some may find this letter disturbing, I find this act of humanity between combatants comforting.

Armed with this additional information Mick found a sketch of the area around Ney Farm. Broebac is the Germanic name for Broembeek, a small channel of water used for irrigation which became an obstacle in the Flanders mud. After reading this, Mick was able to determine that Greg was caught up in the battle in and around Ney Copse and Ney Wood which were only 500 yards apart. As far as I can work out, the German term ‘Totenwäldchen’ translates roughly as ‘Forest of the dead’ which is probably what the German soldiers called the area and which conveys the sight they found after the Commanding Officer of the Irish Guards withdrew his men back behind the Broembeek (called a river by Kipling). However, not everyone got across and that night the Germans ‘shelled vigorously with big stuff all the night of the 13th till three in the morning; stopped for an hour and then barraged the whole of our sector with high explosives till six’.

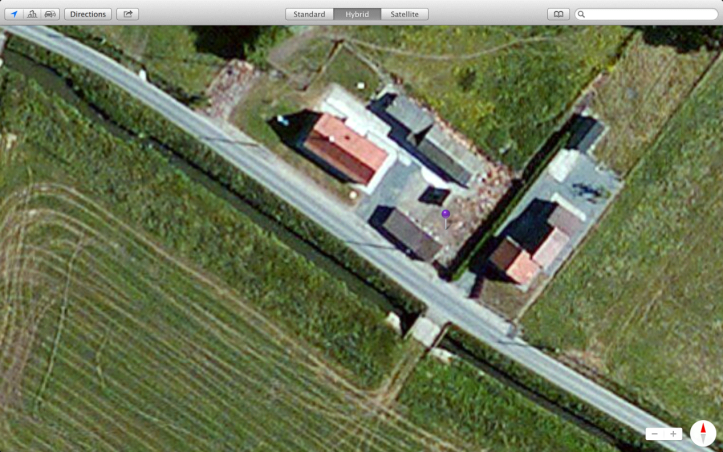

‘They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted’. Ney Copse (5) and Ney Wood (7) only 500 yards apart with the Broembeek clearly visible. Picture: Great War Forum.

‘They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted’. Ney Copse (5) and Ney Wood (7) only 500 yards apart with the Broembeek clearly visible. Picture: Great War Forum.

Searching Google Maps, starting at Langemark cemetery and going west, it only took Mick a minute to find the above satellite picture. It matches exactly the terrain detail on the map above and there is Ney Copse, neatly marked out behind the farmhouse.

Searching Google Maps, starting at Langemark cemetery and going west, it only took Mick a minute to find the above satellite picture. It matches exactly the terrain detail on the map above and there is Ney Copse, neatly marked out behind the farmhouse.

Zooming in shows the Broembeek just over the road.

Zooming in shows the Broembeek just over the road.

Left arrow: Ney Copse; Middle arrow: What was Ney Wood; Right arrow: German Bunker. Just along from this point, past Ney Wood, is a German bunker that was not captured until 1918. So they were still fighting over this parcel of land almost a year later.

Left arrow: Ney Copse; Middle arrow: What was Ney Wood; Right arrow: German Bunker. Just along from this point, past Ney Wood, is a German bunker that was not captured until 1918. So they were still fighting over this parcel of land almost a year later.

Armed with this information, Mick began to plan his visit to Belgium. On Sunday, 27 August 2017, in a chat with his father, Andrew, about his research and planned trip, Mick discovered for the first time that there was a picture of Greg, which his father had inherited from his own father (Andy Hoban, Greg’s brother). The following day, he helped his 90-year-old dad search for it and luckily they found it – a real photographic postcard captioned Cpl SULLIVAN’S Squad Irish Guards Feb 1917. On the right hand edge, Greg had written ‘3 F T R’ (3rd from the right) with an arrow pointing to the second row.

‘We will remember them’ – Cpl SULLIVAN’S Squad Irish Guards Feb 1917 – most probably at Caterham Barracks, Surrey. Picture: Mick Hoban.

‘We will remember them’ – Cpl SULLIVAN’S Squad Irish Guards Feb 1917 – most probably at Caterham Barracks, Surrey. Picture: Mick Hoban.

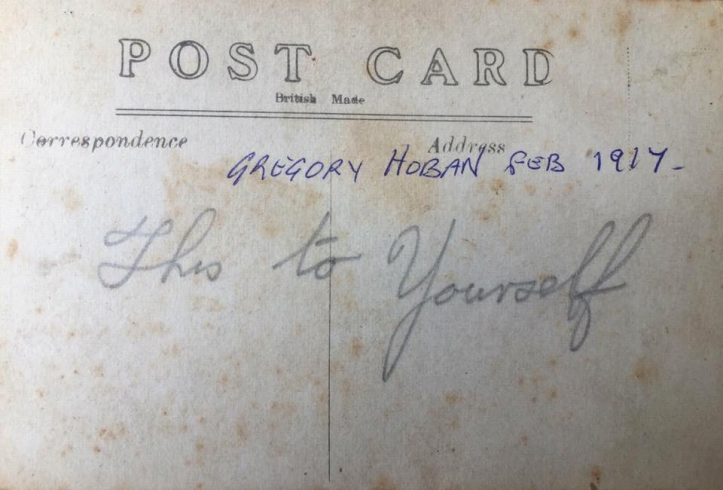

On the reverse of the postcard Greg wrote “This to yourself”. Photo: Mick Hoban.

On the reverse of the postcard Greg wrote “This to yourself”. Photo: Mick Hoban.

The Menin Gate, Ypres, on Friday 15 September 2017 – every night at 8.00 p.m. the Last Post ceremony takes place here. Photo: Mick Hoban.

The Menin Gate, Ypres, on Friday 15 September 2017 – every night at 8.00 p.m. the Last Post ceremony takes place here. Photo: Mick Hoban.

On the weekend of 16 – 17 September, Mick went to Flanders visiting Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing. He found Greg’s name on the memorial to those with no known grave and travelled out to Beekstraat 2, 8920 Langemark-Poelkapelle and visited the area around Ney Farm. I can only imagine the emotions he experienced there.

‘And a glory that shines upon our tears’ – The memorial left at Tyne Cot on Saturday 16 September 2017. Photo: Mick Hoban.

‘And a glory that shines upon our tears’ – The memorial left at Tyne Cot on Saturday 16 September 2017. Photo: Mick Hoban.

Mick found Greg’s name on the Tyne Cot Memorial and paid his respects by leaving his own memorial consisting of four wooden crosses and two notes sent by his sister and cousin.

Mick’s sister, Anne wrote – ‘In memory of Great Uncle Gregory Hoban and the tragedy of a life of promise ended before it began. It has been humbling to learn your story and we will always remember your bravery and ultimate sacrifice.’

Our cousin Eleanor sent the following:

Dear Grand Uncle Greg,

You were the baby of the third Hoban generation family to have lived in Earlsbog, your father Andrew had died in 1907 and your Grandfather Gregory whom you were called after in 1864. It was a tradition in Ireland to call the first born of the family after the father of the baby’s father. But you were also called after your half-brother Gregory who died at 9 years of age in 1879, a year only after he lost his first wife, which must have been sad losses for your father. It was not unusual in the 18th century to call another son the same name, especially if you wanted to keep the name Gregory in the family.

As I drive around the roads in Gowran today and pass by the road you would have taken to Kilkenny to take you on your way to war, I wonder what was in your mind. Like us all taking a journey you looked forward to the adventure I am sure. Thank God for the picture I have seen of your battalion, with you standing proudly in the middle, you didn’t know the horrors of war that must have awaited you and what you must have experienced in those Belgium fields so far from your own green homeland in Earlsbog.

Your mother Ellen must have resigned herself to losing some of her sons to emigration and two of her sons who went to war. The sadness she must have experienced on hearing of your death at 18 and receiving your medals, and the relief she must also have felt when your brother Andrew arrived home.

I am proud of your Grand Nephew Mick Hoban who has taken this journey to see where you died and where you are commemorated at Tyne Cot Cemetery. I hope to make the journey one day.

Rest easy Greg, the Hoban family will always remember your sacrifice, we will never forget.

RIP 1899 – 1917

‘They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old’ – Andrew ‘Andy’ Hoban above (white hair) probably in the late 1960s and below in uniform. Photos: Eleanor Doyle.

‘They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old’ – Andrew ‘Andy’ Hoban above (white hair) probably in the late 1960s and below in uniform. Photos: Eleanor Doyle.

Greg’s older brother, Andrew, also served with the Irish Guards during WWI. He survived the war and died on 14 June 1975, the day before his 77th birthday. He is buried in his home village of Gowran, County Kilkenny. I attended his funeral, but at 14 years old, I was not mature enough to appreciate what he had been through both during the conflict and the years that followed.

Andy Hoban (son of Andrew and now 91 years of age) with his son Mick and grandson Jack. Picture: Mick Hoban. What might Greg’s descendants have looked like?

Andy Hoban (son of Andrew and now 91 years of age) with his son Mick and grandson Jack. Picture: Mick Hoban. What might Greg’s descendants have looked like?

‘Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow’. Photo: Mick Hoban.

‘Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow’. Photo: Mick Hoban.

Greg Hoban’s short life:

- 16 Apr 1899 – Born in Gowran, County Kilkenny, Ireland.

- 22 Nov 1916 – Enlisted in a recruitment office in Kilkenny City, giving his age as 18 years 218 days (actual age 17 years 220 days)

- 24 Nov 1916 – Arrived at Caterham Barracks in Surrey, England

- 02 May 1917 – Received a 3rd class Certificate of Education.

- 01 Jun 1917 – Embarked on a troop ship at Southampton.

- 02 Jun 1917 – Disembarked at Le Havre, France.

- 02 Jun 1917 – Posted to 2nd Battalion Irish Guards at Harfleur (just outside Le Harve).

- 22 Jun 1917 – Joined 7th Entren. Battn. in the Field.

- 28 Jul 1917 – Joined 2nd Battalion Irish Guards in the Field.

- 13 Sep 1917 – Reported missing.

- 08 Feb 1918 – Reported that his body was seen on 13 September 1917 from a list received 25 January 1918.

- 25 Feb 1918 – Officially reported as dead with a date of death ‘on or since 13 September 1917.

Many of you will have spotted my liberal use of quotes from the poem “For The Fallen” by Robert Laurence Binyon in the title and in many of the captions. The fourth verse is very familiar and is often referred to as the Ode of Remembrance. The final lines of the poem promise the fallen that they shall not be forgotten. This is a promise that is renewed every year at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, since 1919 known as Armistice Day. From 1919 until 1945, Armistice Day observance was always on 11 November itself. It was then moved to Remembrance Sunday (the second Sunday of November), but since the 50th anniversary of the end of WWII in 1995, it has become usual to hold ceremonies on both Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday.

3,129 individual crosses and a replica WWI cemetery in Kilkenny Castle for a Service of Commemoration (November 2015) to remember the Kilkenny men and women who took part in the Great War. Photo: http://kilkennygreatwarmemorial.com/

3,129 individual crosses and a replica WWI cemetery in Kilkenny Castle for a Service of Commemoration (November 2015) to remember the Kilkenny men and women who took part in the Great War. Photo: http://kilkennygreatwarmemorial.com/

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known,

As the stars are known to the Night.

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain;

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Sleep well Greg.

Share this: