Many thanks to Lizzy and Caroline for hosting the German Lit Month.

Many thanks to Lizzy and Caroline for hosting the German Lit Month.

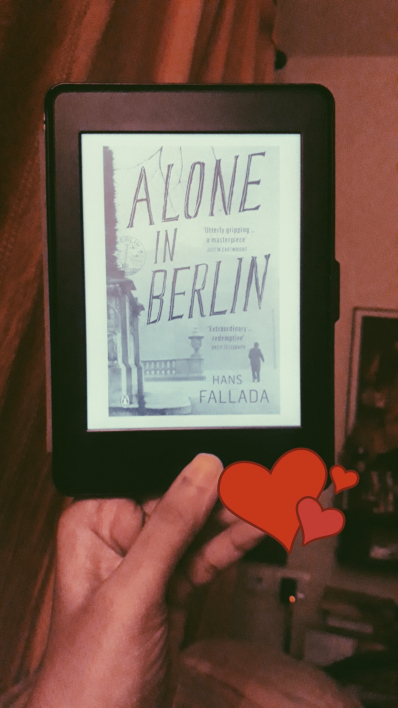

I spent a couple of hours to choose my read and zeroed in on Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin (which is also known as Every Man Dies Alone). The book is translated by Michael Hoffman. For the writing sounds utterly beautiful, I want to believe that Hoffman has done a remarkable job. My friends, who have read the book in German, should be able to validate my opinion. For the nonce, I am basking in the book, in its pain, in its people, in their failures, and in their little triumphs.

Alone in Berlin is about 568 pages long in English. I have finished reading 50% and I couldn’t continue without gushing about how it’s already moving me, questioning my beliefs, and restoring my faith. Hence, I intend to write two blogs about the book. The first part is here.

The war has begun; not the one between countries which is siphoning off peoples’s blood, but the one that the Quangels are waging against Hitler and the Nazis. It’s not an elaborate battle, not a loud protest, but a quiet, systematic one, which is still precarious. They write postcards and drop them in places frequented by all sorts of citizen. They tell Berlin in their own way that Hitler has murdered their only child (their son). They ask Germans to go against the system within their own limits — put sand in machines, do not contribute toward the Winter Relief Fund, raise your voice silently, and so long as the voices are raised, Hitler would know that that kind of people still exist with a modicum of justice in their hearts.

‘The first sentence of our first card will read: “Mother! The Führer has murdered my son.”’ Once again, she shivered. There was something so bleak, so gloomy, so determined in the words Otto had just spoken. At that instant she grasped that this very first sentence was Otto’s absolute and irrevocable declaration of war, and also what that meant: war between, on the one side, the two of them, poor, small, insignificant workers who could be extinguished for just a word or two, and on the other, the Führer, the Party, the whole apparatus in all its power and glory, with three-fourths or even four-fifths of the German people behind it. And the two of them in this little room in Jablonski Strasse!

I read the aforementioned passage many times. I suffer from the inability to name the feeling I experienced when I read it, but it’s the kind of feeling I get when a piece of artwork tears through my heart, illuminates my head, and leaves me exhausted because of exhilaration. There is immense amount of pain in this passage. Despite the couple’s trauma, their fight lifts my spirit. Their son’s death is almost killing their marriage, taking them far apart from each other, but the protest brings them closer as never before. They feel empowered. They understand each other’s love language. Above all, their lives are second to their fight.

Fallada’s Berlin is sprinkled with noble souls. They are the stars in his dark Berlin. They ask me to think about the gravity of my actions. They tell me that random act of kindness saves lives. In spite of the depressing forces, the world wouldn’t be what it is today if those people didn’t stand up for what was just.

Alone in Berlin has arrested me. It’s hard to go on with my life when I know this book is waiting for me, with its engrossing, soulful story. Sample these: A jewess is hidden by a retired German judge, in his deceased daughter’s bedroom. An innocent loafer is chased by the Gestapo, only to make him a scapegoat. A postwoman leaves the Party and the city because his son killed a child in Poland. A widow, whose husband was killed by the Nazis for being a communist, does all she can she to save a man by thwarting the Gestapo. They are all stealing my sleep, but I can’t complain all the same.

Berlin breathes fear into me. It’s hard to live there when my neighbours are unempathetic and are constantly waiting for a chance to prove that I am anti-national, when my colleagues can’t care when I don’t turn up for work, when I can’t mourn my dear ones. In that hostile environment, the Quangels are battered yet brave, exposed yet cautious, falling yet rising. As the Gestapo is driven insane by the Quangels’s audacity, I cheer for them from my bedroom; I mutter a silent prayer under my breath for their battle to go on. I hope Fallada would be kinder to be in the next half.

What are you reading for the German Lit Month?

PS: Thank you, AK, for presenting this book. I heart you. ❤

Advertisements Share this: