As a fan of the film adaption, I was eager to finish off my readings of haunting books with The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty. I was initially worried about how effective the story would be in the written format given the fact that a lot of the horror in the film is so visual, but I was surprised by how well the horror works in the novel through Blatty’s descriptive writing. The way that Blatty builds dread and fear as the paranormal (or perhaps, more specifically, demonic) activity escalates was incredibly effective as well. That being said, I did feel as though the novel lacked Chris’ perspective in the last third of the story, which goes hand and hand with my main concern I had with the novel: the apparent reinforcement of the traditional nuclear family construct, which consists of a father, mother, and child(ren). I was rather upset when I came across this idea in the novel because it was such a compelling story otherwise.

When I first started the novel, I didn’t know how Blatty would deliver the visual horror of the film in a written format. From the possessed Regan spider-walking down the stairs to her twisting around her head like an owl and even projectile vomiting on Father Karras, the horror is as much visual as it is psychological. However, Blatty’s descriptive writing enabled me to clearly imagine these disturbing sights in my mind. For the first time since reading the rat scene (yes that delectable rat scene) in Stephen King’s Misery, I physically cringed while reading. One scene I found particularly scarring was when Regan penetrates herself with a crucifix. Blatty writes, “With a shriek coming raw and clawing from her throat, Chris rushed at the be, grasping blindly at the crucifix while, her features contorted internally, Regan flared up at her in fury and, reaching out a hand, clutched Chris’s hair and, powerfully yanking her head down, firmly pressed Chris’s face against her vagina, smearing it with blood as Regan undulated her pelvis” (205). Just reading those descriptions made my skin crawl. Through these graphic details, I was able to feel the true horror that Chris experiences as her daughter is possessed and all the disgusting blood, mucus, and vomit that goes along with it.

These horrifying and grotesque descriptions highlight the escalation of the demonic activity, which builds with the dread and fear in the novel. From the very beginning of the novel, Blatty introduces the idea of priests battling demons with Father Merrin’s discovery of a statue of the demon Pazuzu (5). Thus, when I read about Regan playing with a Ouija board to talk to “Captain Howdy,” I immediately knew and feared where the story was going (40). However, Chris is not privy to this information, and I was able to slowly experience her fears and anxieties as she tries to figure out what is wrong with her daughter. After initially explaining away her daughter’s unusual behavior as “eccentric attention-getting tactics,” Chris tries to categorize what is happening as mental illness (Blatty 54). Even when she tries to procure an exorcism, she is more motivated by the idea that it will cure Regan’s hysteria that she is possessed than actually exorcise a demon (Blatty 181). However, as Chris slowly becomes unable to truly explain what’s happening to Regan with reason, other subplots develop from her possession, weaving into the story and further raising the stakes as well as the overall feeling of dread in the story. When Lieutenant Kinderman reveals that Burke Dennings was murdered and found with his head turned around facing backwards, there is little doubt that Regan, the last person to be with him when he was alive, is the culprit (Blatty 161). Kinderman’s subsequent investigation made me wonder whether or not, even if they can exorcise the demon from Regan, they would be able to erase the horror she committed while possessed. Not until the epilogue did I stop fearing whether or not Chris and Regan would escape this demon as well as the other problems this possession created. This feeling of dread through the escalation of the activity as well as subplots was one of the most effective aspects of the novel.

While the descriptive writing and escalation of demonic activity, which bred fear and dread, has made this novel stand out from all of the other books I have reviewed thus far, I did have some issues with it. The absence of Chris and her perspective was seriously lacking for me in the last third of the novel. Throughout the novel, she was the emotional force that made me worry about Regan and fear what was happening to her, and just when the priests begin battling the demon who has possessed Regan, Chris fades into the background. Blatty rarely writes from her perspective. While Karras does tell Chris to “keep away from your daughter” because “the more you’re exposed to her present behavior, the greater chance of permanent damage being done to your feelings about her,” Blatty could have at least allowed readers to see how this distancing was really affecting her (Blatty 235). While Chris might not be able to perform an exorcism, leaving her as a side character at the climax of the story seemed like a terrible mistake to me because she was the emotional center of the story throughout most of the novel. This points to a bigger issue in the novel, which is the overall message that seems to reinforce the traditional nuclear family construct. Chris, while a strong and independent woman in her own right, seems to be blamed for the possession because she works. Possessed Regan even tells her “You with your career before anything, your career before your husband, before her” (Blatty 343). This is surely the demon tapping into Chris’ worst fears, but it aligns with the narrative the story is developing about nuclear families. Taking a step back from the characters, the novel is about how a child who, neglected by her working mother, stumbles upon a demon, who must be banished by the ultimate father figure, a priest, seemingly supporting the idea that a family should include a mother, father, and child(ren). While I truly enjoyed this novel, I can’t turn a blind eye to this problematic message.

Ultimately, I found The Exorcist to be a compelling and effective ghost story. Blatty’s talented ability to write descriptively and craft a story that builds fear and dread throughout the novel with this demonic activity is clearly evident. However, the absence of Chris, the emotional center of the novel, at the end of the story might be indicative of a problematic stance concerning the idea that a woman should have a husband in order to raise her child (and save her from demons). On some levels, I say praise this novel with an amen, but I praising a novel with such a message fills me with apprehension.

Work Cited

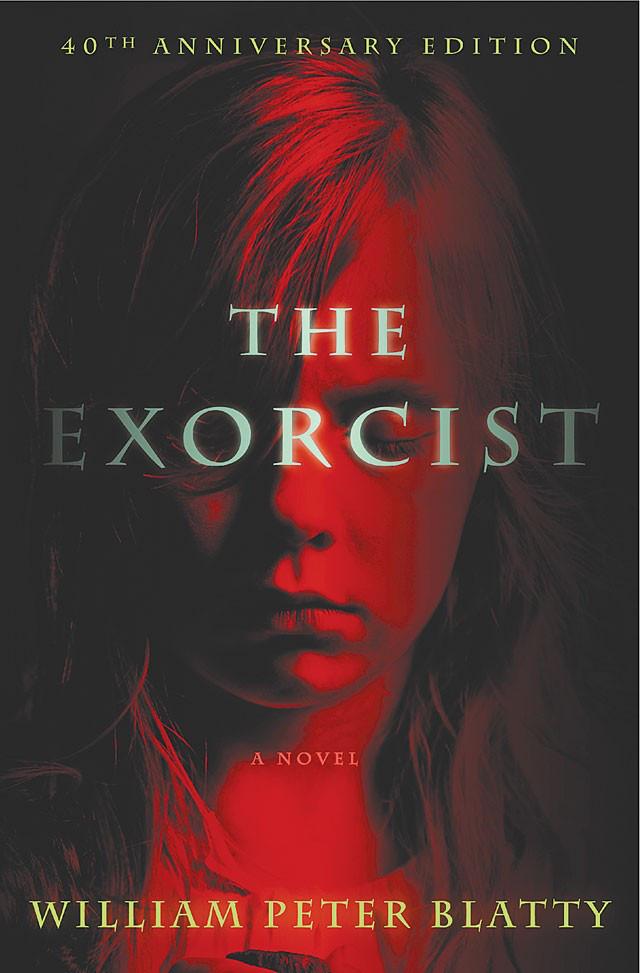

Blatty, William Peter. The Exorcist: 40th Anniversary Edition. Harper Paperbacks, 2011.

Advertisements Share this: