I am writing this post on a Chromebook. At the moment, I have four tabs open, two of which I’m actually using: this one, and another that has YouTube playing Loscil’s album Sea Island, which I’m listening to through cheap earbuds. (The other two tabs are a folder in my Google Drive and a Google Docs file of a syllabus I’m tweaking for the coming semester.) The computer makes this kind of multitasking possible. But it also fragments the experience of writing.

While I was home visiting my family for Christmas, my father showed me a video (also via YouTube) from a series called RSAnimate. (I’ve just opened a fifth tab to locate their homepage and create a link – the 21st-century’s most common form of citation. Do I leave that tab open, messing with my preference for the tab I’m writing in to be the rightmost one, or do I bounce out of my writing to close it?) It was a short lecture (had to open a sixth tab to get the link) by Philip Zimbardo about different orientations toward time. What most stood out to me is Zimbardo’s assertion that “kids” who have grown up playing video games and using smart phones don’t “waste time on single function devi[ces].” That’s a precise term: single function device. It created a link among three objects I’ve recently become interested in, and helped me realize what is driving that interest.

A couple of months ago my mother asked if I wanted a pocket watch that has been in the family for several generations. I did, so she had it repaired and tuned up, and gave it to me for Christmas. I like it an awful lot. Its history, simplicity, and aesthetics appeal to me. (I’ve just opened another tab to visit Google Photos, choose the images I’ll be including here, and download them. I’ll wait until I’ve finished the text itself, though, before inserting the images – sort of a dessert to the meal of composing this little essay.) Partly because I find it beautiful and functional, and partly because it reminds me of my family, I’ve decided to carry this timepiece with me every day.

Thank you, Mom.

Thank you, Mom.

In a seemingly unrelated development, a week or two before finals, I somehow discovered a blog called Pencil Revolution (bounced out quickly to open another tab and link to it). In essays and photographs and reviews of pencils, notebooks, sharpeners, and erasers, this blog develops (bounced out again to skip an ad interrupting my YouTube streaming of the Loscil album) a perspective on pencils that I find compelling. For years I have been using a mechanical pencil to give feedback on student papers, but otherwise I had long ago graduated to the more “adult” writing implement, the pen. Pencil Revolution got me thinking about the tactile and even olfactory experience of working with a wooden pencil. Over the past few weeks, I have experimented with a few different woodcase pencils. The results have converted me. I’m a comrade in the revolution.

An affordable (28 cents) and very high quality pencil – the General’s Cedar Pointe. Beneath it is a Rhodia notebook.

An affordable (28 cents) and very high quality pencil – the General’s Cedar Pointe. Beneath it is a Rhodia notebook.

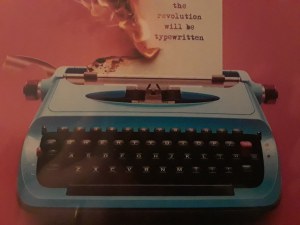

And this newfound love reminded me of an old obsession. One day when I was in college, I came upon an antique manual typewriter, an Underwood, at the local Goodwill store. Its obsolescence, its precise insectile articulations, its musty, metallic smell – something about it spoke to me. So much so that I did a line drawing of it, a sort of homage, with a blooming lotus hovering above the platen. (The logo of this blog is a negative of that drawing.) It was my first typewriter, and over the following few years I collected ten or twelve others. Remembering this collection, which lives in the attic of my parents’ house, awakened a desire to have them restored to working order. And then another serendipitous (the squiggly red line prompted me to open another tab and get the spelling right) turning in the digital wilderness brought me to a film called California Typewriter, which I mentioned when my sister asked what I might like for Christmas. (You know by now that I jumped to out again for that link.)

From the DVD cover of California Typewriter

From the DVD cover of California Typewriter

Before I was able to watch the film, Dad showed me the RSAnimate video, and Zimbardo’s term revealed that these three objects – the pocket watch, the pencil, the typewriter – are stars in the same constellation whirling in slow motion through my sky. It’s not about nostalgia, or mostly not, anyway. Of course, most of us have memories of using pencils, about which we may or may not wax nostalgic. I don’t have any clear or striking memories of pencils, per se. And when I fell in love with that typewriter, when my mother gave me that watch, I had no experience of either to be nostalgic about. Nor is it some fanatical rejection of technology that makes me love these things. The typewriter is a sophisticated, highly specialized example of industrial engineering and manufacturing, as is the watch. What unites them, along with the pencil, is their status as single function tools. (The album has come to an end. Do I flip over to YouTube to get some new sounds rolling?)

Of course you can use a pencil to keep your hair up, or as a weapon in schoolchildren’s games. A pocket watch might double as a paperweight. A typewriter makes a good percussion instrument. You can use these tools otherwise than to check the time, to write a thank you note, to type a manuscript, but they are designed to aid you – and, in the case of very elegantly designed tools, to encourage you – in a single kind of task. (It is snowing here, and I keep checking the weather in response to low-grade anxiety about losing power. To my relief, the air is currently moving at zero mph.) Because I teach writing, and because my students tell me over and over and over that their digital lives disrupt their non-digital lives, that the laptops that college seems to require actually make it more difficult for them to focus on the academic work supposedly at the center of college life, I am interested in single function tools.

I also like working on my Chromebook. Quite a bit. I like listening to Loscil’s meditative sounds as I update my class website or maintain my inboxes. I like the astounding convenience of digital research. I depend on digital navigation. I get inspired by some of the things I see on Netflix. I even assign a digital portfolio in my writing class. But I have found that I am most productive as a writer when I am working with pencil and paper. With single function tools that do not invite me to distract myself from that work. Instead, they invite me to invest myself in what I am doing.

California Typewriter is a wonderful movie. It is an invitation, in fact, to shut off the DVD player and sit down at the typewriter, or pick up a pencil and open a notebook. It is an invitation to live and work with a different kind of focus than the 21st century generally demands. One of the voices in the film is that of Richard Polt, who has written a concise and moving statement of this ethos I find emerging in my own life. I’m giving him the last word today:

- More