Much of this year was spent getting used to my new full-time high-pressure job in an unfamilar town surrounded by strangers who soon became good friends or important contacts.

Luckily, despite an increasingly busy schedule, I still found time to read a few books. These were my favourites.

Tenth of December – George Saunders Copyright: Bloomsbury.

Copyright: Bloomsbury.

Hype can be a dangerous thing.

A couple of pull-quotes on the front cover of a book can be good for attracting potential readers, but it’s all-too-easy to overdo them, to plaster the cover and front-load the first few pages with so many superlatives that the readers’ expectations become so impossibly-high that the book can no longer reach them.

This was the case with The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead, a novel following the perilous journey of an escaped slave, which was showered with prizes and praise earlier this year.

Along with the usual short snippets from positive reviews on the front cover, the book had an extra cardboard flap behind the front cover full of lengthy paragraphs promising that the story was an unforgettable future classic with writing that was similar to half a dozen different literary greats, followed by a few pages which featured even more examples of critics singing its praises at the top of their lungs.

This absurd amount of hyperbole ended up hurting the book instead of helping it.

The Underground Railroad is a well-told tale with a great protagonist, an interesting structure, fully-developed characters and moments of extreme tension, sorrow and joy, yet I still felt a slight twinge of disappointment when I finished it because it had been merely excellent rather than an unquestionable masterpiece.

George Saunders also received a lot of acclaim this year for his new novel and I noticed that one of his short story collections, Tenth of December, had been gathering dust on my shelf, so the time seemed right to give it a go.

I glanced warily at the cover quotes suggesting that it was ‘the best book you’ll read this year’ and that George Saunders was ‘the best short story writer in English’, though compared to The Underground Railroad‘s cover this was fairly restrained and understated.

After skipping the introduction because it was 20 pages long – longer than some of the actual short stories in the collection – and because it began by repeating the ‘best book you’ll read this year’ comment which made me concerned that the rest of it would be similarly hyperbolic, I began the first story.

250 surreal, whimsical, disturbing, intense, laugh-out-loud funny and – quite often – extremely moving pages later, it was clear that the promises of the cover quote had been kept.

These stories are incredible.

They range from slice-of-life character dramas to sci-fi-inflected satires, they focus on dark and uncomfortable subjects but also have a silly sense of humour that doesn’t feel out of place, and Saunders writes with sympathy for his characters while putting them into desparate situations and observing how they cope.

So, with more than a little surprise, I must echo what the critics have said, because, once in a while, against all odds, despite their fondness for hyperbole, they’re right.

George Saunders has written the best book you’ll read this year.

The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood Copyright: Vintage.

Copyright: Vintage.

At the start of the year, soon after America inaugurated its new president, there was a sudden boom in sales of classic dystopian literature. What a coincidence.

The biggest bestseller was The Handmaid’s Tale, a chilling look at a society where women are treated as little more than walking wombs after a catastrophe which decimated the population of the USA and lead to widespread scapegoating of Muslims was used by an extreme right-wing Christian regime to stage a coup and strip women of their rights and freedoms.

In this new America, many women are assigned to wealthy married men as Handmaids, mistresses who must procreate with the head of the household since radiation has left the wives sterile.

Offred is our narrator and guide to this horrible society. She tells us about her miserable life, the life she once had, and how she got from there to here – the family and friends she lost along the way, the strict inhumane Aunts who taught her the rules of this new order, the day-to-day life of a Commander’s slave.

Her tale is a testimonial, a historical document from someone living under a totalitarian regime who wants to tell future scholars what it was like to live in such miserable conditions.

Abortion doctors are strung up on hooks on the Wall that encloses the community, uncomfortable quasi-religious ceremonies and rituals are unavoidable, women less fortunate than Offred (yes, that’s possible) regard her with hate and jealousy.

It’s all very bleak, yet it reads like a page-turning thriller with sharp lashings of wit, sympathy for characters who at first glance seem callous and even the possibility of hope.

Her story provokes plenty of questions that remain unanswered due to Offred’s limited perspective and it ends on an ambiguous note that’s frustrating but rings true, as it provokes the same feeling that anyone who’s ever perused personal letters in a history museum exhibit about any historical atrocity, only to find that the letter ends with a paragraph saying ‘It is unknown what happened to X after this was written, but there are several possibilities…’ will find familiar.

Berlin Stories – Robert Walser Copyright: New York Review of Books.

Copyright: New York Review of Books.

In May 2016, I travelled to Berlin for three weeks as part of a work experience project. While I was there, I bought numerous books which were by German authors or about German history or just had the word ‘Berlin’ in the title because I planned to read one of them during that same three week period next May, and the May after that, and so on.

As this May began, I didn’t have the time or concentration to commit to a massive tome, so Robert Walser’s slim collection of even-slimmer pieces of writing about his time living and working in Berlin was the perfect book for this hectic period.

Rarely longer than four pages each, many of these notes and musings do a lot with very little. Walser’s joy in describing the minutiae of city life is infectious, expressed in lengthy paragraphs of conversational, personable, and endearingly rambling prose.

Sections near the end of the book have a more reflective and melancholic mood but are no less engaging and wonderfully imagined.

It’s like an old, exceptionally eloquent traveller telling you about where he’s been and though his anecdotes are all rather mundane, his storytelling ability and careful observations elevate them immensely.

It usually takes me a couple of minutes to read a couple of pages yet I spent considerably longer on some pieces in this book, like ‘Friedrichstrasse, ‘The Metropolitan Street’ or ‘The Theater, A Dream’, as I kept going back and re-reading, pausing on a particularly nice turn of phrase, or just waiting a while before reading the last couple of lines to let it all sink in.

The bar has been set very high for whatever I decide to read next May.

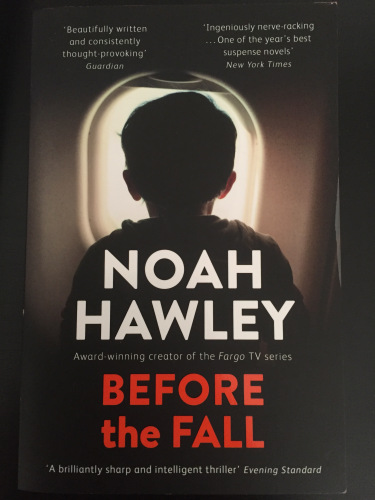

Before the Fall – Noah Hawley Couldn’t find a big enough pic of the UK cover, so I took my own.

Couldn’t find a big enough pic of the UK cover, so I took my own.

This tense, character-driven thriller about a mysterious plane crash, written by the creator of two of the best shows in recent years, seems almost like it was tailor-made for me.

After all, a character-driven thriller about a mysterious plane crash was a teenage obsession of mine, so when I discovered that the creator of Fargo and Legion had somehow found the time to write a book in-between planning, writing and directing the two shows, it was an obvious instant-buy.

Before the Fall examines the malleability of truth by looking at how an amoral journalist at a ratings-hungry 24-hour news network covers the aftermath of the disaster and how he affects the reputations of the survivors and the relatives of the dead through his wilfully-misleading and unethical reporting.

Down-on-his-luck artist Scott Burroughs becomes a last-minute addition to the list of passengers on a private jet’s flight to New York City after he meets the wife of a TV mogul hours before take-off.

When the plane unexpectedly crashes into the sea, Scott rescues the only other survivor, the mogul’s five-year-old son, by swimming several miles to shore and is quickly scrutinised by the media and the government.

As Scott attempts to adjusts to his new life in the spotlight while coming to terms with the trauma and tragedy he’s experienced, flashbacks reveal the personal histories of everyone else on the flight and offer up several possible causes for the crash before some shocking and satisfying revelations in the novel’s final pages.

This page-turner is a wonderfully well-written book, full of richly-developed characters and intriguingly-structured, a gripping and satisfying read that’s tense, funny and often quietly, heartbreakingly sad.

It proves that Noah Hawley is enviously multi-talented. Hopefully, he can find time to write another novel in his increasingly-busy work schedule.

Franny and Zooey – J.D. Salinger Copyright: Penguin.

Copyright: Penguin.

This “pretty skimpy-looking book”, as Salinger himself calls it in the preface, was an unexpected highlight of the year for me.

I say unexpected because the first story, in which Franny Glass spends a day with her college boyfriend that triggers a nervous breakdown, was thoroughly underwhelming. Perhaps my expectations were too high but it was fairly uninteresting and luckily the second story more than made up for it.

Remarkably, Salinger has made an engaging, painful and entertaining read out of a plot that contains little more than a letter full of family history, two lengthy conversations which turn into heated arguments, and one that doesn’t.

Zooey’s section of the book is narrated by his older brother Buddy, who calls it a “prose home movie” that lets us witness a typical day in the life at the Glass residence.

Despite being absent during the events of the actual narrative, Buddy’s presence is still keenly felt, though not as much as Franny and Zooey’s late eldest brother Seymour, who is mentioned repeatedly in hushed, reverent tones that speak volumes about how much the Glasses miss him.

All of the Glass children had been the stars of a radio quiz show and listener feedback was split: “the Glasses were a bunch of insufferably ‘superior’ little bastards that should have been drowned or gassed at birth… [or] bona-fide underage wits and savants, of an uncommon, if unenviable, order.” If your opinion of them falls into the former camp, this will be the longest 150 pages you’ve ever read.

While Zooey reads a screenplay in the bath and Franny lies in a sobbing, starving heap on the living room sofa, their long-suffering mother Bessie is worried sick trying to figure out what’s wrong with her daughter while also dealing with the painters that are redecorating the house.

She has the achingly-relatable struggle of juggling problems that are immensely important and monotonously mundane while trying not to collapse under the stress of it all.

It was surprising, and slightly concerning, to see elements of my own personality distorted, twisted and unflatteringly amplified in certain members of the Glass family.

Zooey’s well-read but comes off as smug and self-important, his sarcastic smart-arsery regularly crosses the line from cheeky to cruel and his apologetic self-awareness about this bad habit doesn’t make his harsh jibes any more forgiveable.

Buddy’s need to reflexively criticise his own work as a self-deprecating tactic to stop anyone else mocking it quickly becomes irritating rather than endearing.

Mrs Glass’ unhelpful but well-meaning concern for the children who seem to find her endlessly annoying is met with constant disrespect and both of the titular siblings struggle with crises of identity and second thoughts about their life choices.

Though it could easily be argued that Franny and Zooey is a rather aimless book of annoying people bickering with each other, its characters are so well-realised that it’s a shame there’s only two more ‘skimpy-looking’ books which feature them.

Salinger is adept at creating characters who are equally loved and loathed by his readers (see also: Holden Caulfield) and writing them in a way that feels real and resonant.

Honourable Mentions: The Underground Railroad – Colson Whitehead, Chronicle of a Death Foretold – Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Look At Me – Jennifer Egan, Guards! Guards! – Terry Pratchett, MR ROBOT: Red Wheelbarrow (eps1.91_redwheelbarr0w.txt) – Sam Esmail and Courtney Looney, Advertisements Share this: