There are very few cinephiles, film critics, or industry insiders who would not have Alfred Hitchcock somewhere near the top of their list of best directors ever. In the most recent Sight and Sound list of the best films of all time (possibly the most comprehensive “best-of” film list) Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo came out on top. But more than that, Hitchcock himself was easily the most represented director as 390 different voters cast their votes for 21 of his films. His career is one that has spanned the silent film era, the classic Hollywood system, and the post-production code era. And in each of those eras he has succeeded. The word “legendary” gets tossed around to the point that it has lost most of its meaning, but it is an entirely appropriate label to give to the master of suspense.

And yet it is surprising just how misunderstood Hitchcock’s career is. Part of the misunderstanding comes from him being most associated with the horror film Psycho and thus wrongly labelled as a horror director. I know this, because I made that exact same mistake many years ago when I was trying to put together a horror movie marathon for Halloween and rightly chose Psycho but then blindly chose Vertigo believing it was a horror movie. While this serendipitously gave me one of the best double-features of all time, it most certainly was not what I had in mind. The truth is while Psycho is his most famous movie, it probably is also his least typical. Diving deep into Hitchcock’s catalogue instead reveals that the man had a wide and varied career.

So for this list, the criteria is simple. If he directed it, it’s eligible. Let’s go.

10. THE BIRDS (1963)

Creating the previously unbeknownst fear of avian creatures, Hitchcock’s The Birds is a masterclass in creating and sustaining an atmosphere of tension. For the first half of the movie, it plays more like a romance or a comedy as Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) visits the sleepy town of Bodega Bay to pursue her romantic interests with Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor). But slowly and surely those romantic interests start to take a back seat as the local birdlife begins to behave erratically and then violently. The genius of this movie is that Hitchcock refuses to give any exposition as to what could have possibly motivated this shift in avian behaviour. Instead the birds are agents of chaos, attacking randomly without any discrimination towards their victims. The movie is also aided by the ominous and music-less soundtrack as well as the groundbreaking special effects which help create a truly visceral experience. And the final unbroken shot is proof-positive that terror can be achieved and maintained even when nothing happens at all.

9. THE LADY VANISHES (1938)

An under appreciated quality of many of Hitchcock’s films is how much fun they are. The Lady Vanishes deftly combines romance, melodrama, and mystery to create an effortless and entertaining puzzle of a movie that is equal parts comedic and thrilling. The premise is simple: On a train ride back from an unnamed European country Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood) discovers that an elderly travelling companion has disappeared. Yet most of the other train passengers do not remember ever seeing the missing lady, and suspect Iris instead might be hallucinating from a blow she received earlier. The underlying mystery proves to be the perfect setup for Hitchcock to wield his magic, where every innocuous action has the potential to have some bearing to unearthing the mystery of the lady’s disappearance and the deeper Iris goes the more secrets get unearthed is unexpected and clever ways. The movie is important as one of Hitchcock’s last British films until the 1970s, but it is also a delight.

8. NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1958)

North by Northwest, made four years before Dr. No, is as entertaining a spy-romp as any in the James Bond series. The story uses the well-utilized Hitchcock trope of mistaken identity but this time with the star power and charisma of Cary Grant as the ad executive Roger Thornhill who is mistaken for a spy, creating what is possibly the closest thing to a Hitchcock blockbuster. The set-pieces alone are worth the price of admission whether it’s the iconic airplane chase scene or the final confrontation on Mt. Rushmore. Most of the pleasures of this movie are surface level and most of what Hitchcock does in this movie is tongue-in-cheek, but he has so much fun doing it that you can’t help but get caught up in his giddiness. It is perhaps Hitchcock’s most purely entertaining film as his propulsive plot has Grant careening from crisis to crisis to create an exhilarating ride from beginning to end.

7. THE 39 STEPS (1935)

Hitchcock’s first true masterpiece like North by Northwest uses the same mistaken identity trope, but it also is the perfect example of Hitchcock’s concept of the MacGuffin – namely the use of an object or idea that exists to simply help advance the plot regardless of what that thing is. In this case it is the “39 steps” which are mysteriously uttered by a spy shortly before dying in the arms of unsuspecting everyman Richard Hannay (Robert Donat). Having stumbled into a conspiracy larger than him while also being accused of being the murderer of said spy, Hannay is thrust into an adventure that takes him all across England as he tries to solve the mystery of the “39 steps” while also clearing his name. While Hitchcock would go on to make better movies with higher ambitions, The 39 Steps represents just another example of Hitchcock taking pulpy material and elevating it by directing it to perfection.

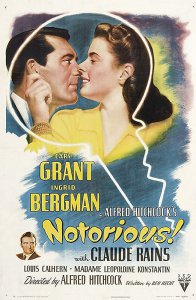

6. NOTORIOUS (1946)

Part of the joy of Hitchcock moving to Hollywood is that he got to work with the very best stars from the golden age of cinema and no stars were bigger than Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman who star in this spy film-noir. Bergman stars as Alicia Huberman a daughter of a convicted Nazi-spy who is recruited by Devlin (Cary Grant) to counter-spy for the American government. With typical style Hitchcock deftly weaves the story between spy thriller and romantic melodrama, moving the action to Rio de Janeiro and throwing the underrated Claude Rains into the mix. The movie contains perhaps the best camera work in a Hitchcock movie and a great example of the master’s visual style. Yet unlike all the other films on this list, this is a movie that Ingrid Bergman basically steals from Hitchcock as she is the unquestioned star here. Besides being an unquestioned beauty, her acting ability has and always will be some of the best ever to be captured in celluloid and Notorious is no exception.

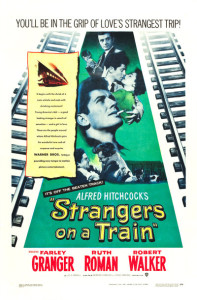

5. STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1951)

I realize that it a bold claim to make given Hitchcock’s track record but Strangers on a Train is possibly his most diabolical movie. The story of two strangers who randomly meet on a train and decide to kill the other’s intended target is one that is rife with potential and fortunately for us, Hitchcock is up to the task of squeezing every ounce of macabre glory out of it. The interplay between the tennis star Guy Haines (Farley Granger) and the charming sociopath Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) is one for the ages as they start out as reluctant partners and eventually end up as mortal foes. Bruno in particular is one of Hitchcock’s great creations, as he lays out the template for a kind of serial killer that would be imitated endlessly in cinema from then on. And in something as ordinary as a tennis match, we see the precision and filmmaking technique that made Hitchcock the undisputed master of suspense and tension.

4. SHADOW OF A DOUBT (1943)

Hitchcock is rightly known as the master of suspense. His “bomb-theory” to creating and sustaining suspense was that whenever possible, you need to give the audience more information than any of the characters in the film. And Shadow of a Doubt is a prime example of that theory in action. When young Charlie (Teresa Wright) is suddenly visited by her namesake uncle (Joseph Cotten) out of the blue, it is almost immediately suspicious. Those suspicions immediately become more pronounced when two investigators searching for the “Merry Widow Murderer” shows up in her sleepy town. It does not take a genius to figure out who might be the prime suspect. Unlike most mystery thrillers, Hitchcock is not interested in shrouding the mystery but lays it out in the open for all to see. But the movie also clearly shows that it is not the withholding of information that creates tension, as the movie becomes a slow-boiler of suspense as we wait with baited breath to see if Charlie will be able to put all the pieces together in time, and more importantly convince others to do the same. As the movie which Hitchcock described as his favourite, it is the perfect introduction to his impressive body of work.

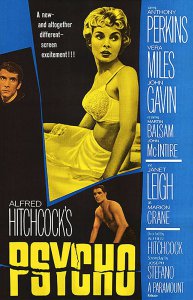

3. PSYCHO (1960)

We all know the shower scene even if we’ve never seen the movie. Thanks to a television prequel Bates Motel we also know more than we probably need to know about Norman Bates. But all of that still manages to undersell just how great this movie is. The first 50 minutes or so of this movie may just be the greatest stretch that Hitchcock has ever directed. It is testament that even the most B-movie material can be elevated far above that if it is directed and produced to perfection. No matter how many times I watch the movie, the shocking murder at the centre still comes as a shock not just for the viscerally horrific way it was shot but because Hitchcock has successfully lulled us into expecting a conventional storyline and then yanks the rug out from underneath us. Unfortunately after that shocking scene, the movie struggles to regain the exhilarating momentum of the first 50 minutes, settling into a conventional investigation story (with still a few shocks up its sleeve). And the epilogue, which I just have to believe was studio-mandated, is unfortunate and unnecessarily expository. Still, those faults are only bad enough to knock this movie down to number 3. It is definitely worth a spin.

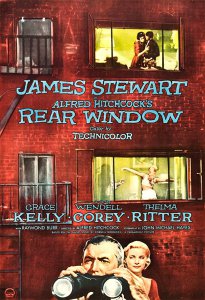

2. REAR WINDOW (1954)

I have a theory (that I’m sure is not original) that the key to truly great creative work is by imposing limits on yourself. And I almost always point to Rear Window as my example par excellence. Hitchcock famously shoots this movie using only one backstage set that depicts the back alley of a group of New York apartments, and shoots the movie exclusively from the point of view of the wheelchair-bound photographer “Jeff” Jeffries (James Stewart) who wiles his summer days away by spying on his neighbours. From these limitations, Hitchcock weaves a fantastic thriller when Jeffries spots a potential crime being committed and he, along with his effervescent girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly) and sharp-as-nails nurse Stella decide to investigate on their own. By limiting our view to Jeffries apartment, we are at one level (seemingly) safely detached from the action but also agonizingly helpless as the mystery unfolds. The interplay between these two dynamics truly creates a boiler-room atmosphere from beginning to end and simply confirms the old cliche that less truly is more.

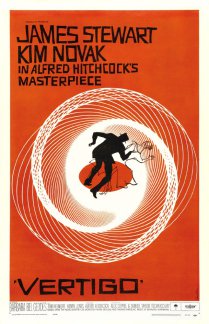

1. VERTIGO (1958)

To anyone who knows anything about Hitchcock (or read the intro to this piece) it should not come as a surprise that Vertigo comes out on top. On the surface it is a highly predictable choice, but there is no doubt that it is well-earned. As a novice film critic, there are some films that I sometimes feel unable to review just because it it a great and daunting task to try and capture how good the movie is. Vertigo sits firmly close to the top of those films. Whether it is the fantastic opening credits by Saul Bass, the methodical car chase that occurs in the beginning of the movie, or the sweeping Bernard Hermann score that haunts every frame, or the stunning transformation scene at the film’s climax (you know what I’m talking about) that is in contention for one of the greatest scenes of all time, the movie is iconic from beginning to end. The hypnotic power of the movie means that every few years or so I find myself lured back into its presence. And unlike most movies, its power seems to just grow the more I see it.

Also as a final aside, Vertigo kicked off what had to be the greatest 4-film stretch of any director’s career (Vertigo, Psycho, North by Northwest, The Birds). The fact that this four-film stretch only represents the tip of the iceberg in terms of great films in his career simply means that it isn’t an exaggeration to call Hitchcock the greatest director ever. The hype is real.

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

Share this: