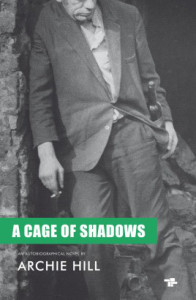

A Cage of Shadows, by Archie Hill, is an autobiographical account of the author’s troubled early life. He was raised in the Black Country during the depression of the 1930s, the eldest but one of eleven children. His father was an abusive alcoholic which exacerbated the family’s poverty. Archie nursed a rage against his home circumstances that moulded what he became. He had mentors in his father’s friends who taught him how to poach and steal food from farms and local woodlands. His admiration for these men, and the hatred of his father, never waned.

I rarely read autobiographies having been turned off the genre by numerous self-aggrandising celebrity memoirs, the proliferation of misery memoirs that followed the publication of Angela’s Ashes (Frank McCourt), and the questioning of the veracity of these and the likes of A Million Little Pieces (James Frey) and Three Cups of Tea (Greg Mortenson). A Cage of Shadows was first published in 1973 so predates these works. It was also the subject of controversy when Archie’s mother successfully sued for libel resulting in a rewrite that removed most of the sections where she is mentioned. The version I review here is a reprint of the original, described now as a classic, which was critically acclaimed when first released.

Whatever the truth or otherwise of the story, what is portrayed is a life of bitter hardship that was endured by too many. With jobs hard to come by – three men ready to take any vacancy – worker safety and renumeration were pitifully scarce. Archie had part-time work in an iron foundry while still at school and describes the conditions that damaged the employees’ health. Throughout his childhood he dreamed of escape.

The hand to mouth existence – where Tally Men and Means Test Men wielded their small power like little dictators – was relieved by drink and savage entertainments. There were illegal cock fights, rat killing contests, and bets taken on bare knuckle fighting between the men. The vernacular comes across as authentic although some of the terms would now be deemed offensive. The camaradarie perhaps explains why some look back on such difficult times with a degree of affection.

Archie did eventually get out but it was not the escape of his dreams. He enjoyed a stint working the canals, briefly falling in love, before signing up for military service with the RAF. From here he joined the police but was by now struggling with alcoholism. He did time in prison, in mental asylums, and ended up a ragged vagrant in London’s underbelly.

Archie’s account of each of these experiences is told with unsentimental candour and a degree of self-reflection. Of his poaching he notes that wild animal killing was deemed acceptable by those in authority if done as a sport but not to feed starving families. The antics may rightly be frowned upon but this is life lived on a hard edge. Many of his problems may have been self-inflicted but when Archie fell he could find no safety net.

The writing is assured offering a window into a life that reminds readers of the truth behind what some still refer to as ‘the good old days’. It is intriguing for the insights given, the imaginative reuse and recycling, the petty thievery that enabled survival. Poignant in places and sometimes brutal but with certain attitudes that remain all too familiar. This is an account steeped in history worthy of contemporary reflection.

My copy of this book was provided gratis by the publisher, Tangerine Press.

Advertisements Share this: