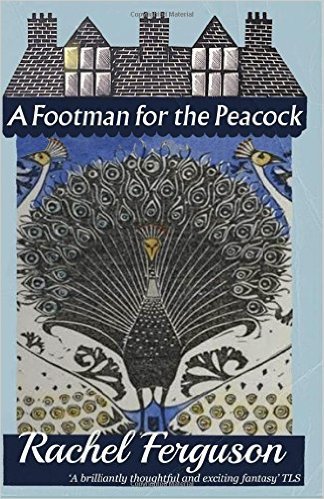

A Footman for the Peacock

By Rachel Ferguson

Out now. A Furrowed Middlebrow book (an imprint of Dean Street Press). £9.99 paperback, also available as an ebook.

For more about this independent publisher and the imprint, visit: http://www.deanstreetpress.co.uk/main/middlebrow

Rachel Ferguson will be familiar to fans of Persephone and Virago books. The former published her novel Alas, Poor Lady (1937), the latter, her best known work, The Brontes Went to Woolworths (1931). A Londoner most closely associated with Kensington, where she spent the bulk of her life, Ferguson had a busy life. She was a suffragette and then attended drama school. For a little while she acted and taught dancing. During World War I she served in the Women’s Volunteer Reserve, before becoming a drama critic. For years she was the columnist “Rachel” in Punch magazine. She wrote novels (precisely how many remains the subject of debate, but at least nine) and nonfiction, including a posthumously published memoir. During the last part of her life she devoted herself to two causes: decayed gentlewomen and performing animals, doing time as president of the Kensington Kitten and Neuter Cat Club. She died in 1957. (This biographical info comes from the Virago edition of Brontes.)

Ferguson sounds like a marvellous eccentric, though as I’ve noted elsewhere (https://randallwrites.wordpress.com/2016/01/28/shopping-list/), some of her political and social views are tough to swallow. Nevertheless, she was an insightful observer of human foibles, which she skewers magnificently and hilariously in all of her work. She understood interior life and the importance of fantasy to our emotional well-being, excelling at incorporating it into her work. A.S. Byatt, in her introduction to Brontes, noted “the delicacy and variety of Rachel Ferguson’s exploration of the edges of the real and the dreamed of, or the made up, or the desired.

A Footman for the Peacock came out in 1940. It’s set in the early days of the brand new world war, though it contains numerous flashbacks to less fraught times. This edition contains an introduction by Elizabeth Crawford (which reads as if it may be a group intro to all three Ferguson reissues). She identifies, “A Family — a House — and Time” as key ingredients in Footman. The house is Delaye, occupied by assorted members of the aristo Roundelay family. Without money or transport, they’re frequently trapped in the house — without adequate supplies — living at the mercy of kindly neighbours and infrequent bus service to the nearest village. They come together ritualistically at prescribed intervals, and yet they contrive not to be bored.

To be sure, this is a slow read. Like Henry James, Ferguson became more baroque as her career progressed, and some sentences pile clause upon clause, requiring a second go to capture the sense of them. Plot-wise, no one will mistake this for a thriller, even though there’s a Nazi-signalling peacock, a centuries old mysterious death, and the looming threat of annihilation at the hands of Britain’s enemies. Really, it’s a story about people who resist change, and why. It’s a reminder of how the past haunts the present, and the benefits of making amends. It’s about how families get trapped in patterns of behaviour, by the strictures of social class, and by economic difficulties.

Do make time for the novel. It is studded with delightful stories, funny set pieces, and sharp social criticism. Some reviewers have described the Roundelay family as loathsome. I found them sympathetic, even though they’re comically self-absorbed. After all, the married couple at the heart of the novel love one another and their children. Servants, while unquestioningly trapped below stairs in the hierarchy of Delaye, are largely treated with respect. Ancient, penniless relations and retainers are sheltered — though the same cannot be said for evacuees. The scene where the Roundelays, ambushed by a government official, repel mothers and babies, orphans, and other needy cases, is one of the funniest in the novel, and it’s perversely hard not to root for them.

Elsewhere, Ferguson provides colourful, insular locals who speak a strange patois that’s part French, part god knows what and who, like all such rustics in novels of this ilk, provide a taproot to the region’s past.

Finally, there is an amusing, open-minded vicar. He befriends the youngest Roundelay daughter, Angela, the girl most troubled by deep feelings and a strange affinity for the peacock. She suspects it might be a reincarnation of the house’s former running footmen, and that it’s having a relationship of sorts with the housemaid, herself descended from a line of women who have always served the family. She’s not wrong.

Along the way Ferguson finds time to mock the press and other institutions, and takes bullseye potshots at England’s wartime spirit. Evelyn Roundelay receives a letter from her sister, in London, saying, “We had an air raid warning in church yesterday just after the P.M.’s speech, but nobody turned a hair; they thought it was something gone wrong with the organ, and in short, we played the ukulele till the ship went down.

“If you’re short of torches, I’m told in some of the shops that they’re expecting a consignment of American batteries. They’ll cost 11d., I hear — about three-quarters more than the proper price, so America wins the war once again, at the beginning of it, this time, instead of the end. Meanwhile, I guess and surmise and ‘low our cue is to be terribly polite about the U.S.A. for some months yet, with plenteous reference to The Mayflower, our roots in common soil and great traditions of liberty, so wise up your cheer-squads to whoop it up for Gopher Prairie, fair city of hundred per-cent two-fisted, red-blooded, up-and-coming reg-lar fellows.”

I’ll stop laughing long enough to say that if you’re new to Ferguson, and, say, a fan of novels such as Cold Comfort Farm, that I predict you’ll enjoy this hilarious novel in which nothing — and everything — happens.

Advertisements Share this: