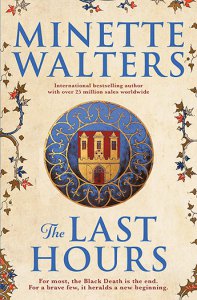

The Last Hours, by Minette Walters, heralds the welcome return of a highly regarded author who has not published a new novel in more than a decade. In discussing why, she said:

“To be honest, I got to the point where I was beginning to be so stressed out and needed a break. I’m a very slow writer, and then I get stressed out with publicity and the whole business of getting a book out. And then it’s people’s expectations. I suddenly felt that I needed a life.”

Unlike her previous work this new book is historical fiction. In talking about her change of direction the author admitted she had grown tired of the genre where she made her name:

“I love to innovate and, while it pleases me greatly that I’ve helped create the genre of psychological crime fiction, I’d be going against my nature if I didn’t look towards different horizons,”

The Last Hours is the first in a proposed two part series set in and around Dorset where the author now lives.

“Each time I leave my house, I know that somewhere beneath my feet is a plague pit,”

It offers a captivating and chilling account of life as it would have been for lords and serfs in England, 1348, living in fear of a wrathful god and facing a virulent plague that kills victims within days.

The story opens on a hot summers day in the demesne of Develish, Dorsetshire. The lord of the manor, Sir Richard, is setting out on a journey to seal the betrothal of his fourteen year old daughter, Eleanor, to Peter of Bradmayne, the son of a neighbouring lord. Eleanor is unhappy with this choice of husband and blames her mother, Lady Anne, for not securing a more congenial match. She takes out her anger on their indentured serfs, particularly the handsome bastard son of a bondsman, Thaddeus Thurkell.

Sir Richard and his entourage travel to Bradmayne where their host plies Sir Richard with copious quantities of food and drink as he tries to relieve him of the promised dowry. Sir Richard’s Norman fighting men stand guard while his Saxon bailiff, Gyles Startout, observes what is happening beyond the manor’s boundary wall. The villagers are restless and prevented from entering. After several days their unrest turns to fear. There is news of a deadly sickness spreading from the port of Melcombe. While only the peasants are dying few seem to care but when Peter of Bradmayne takes ill the Develish men flee.

Lady Anne had long worked behind her cruel and selfish husband’s back to improve the lives of their serfs. When she hears of the sickness she recognises the danger and acts in all their interests. The entire village moves into the manor which is protected by a moat. Food is stockpiled and the bridge is burned. None know if any inside already carry the plague.

As time passes fear of sickness is only one of the challenges Lady Anne must overcome to maintain order. Food distribution must be carefully controlled and the boredom of people used to days filled with hard labour assuaged. Eleanor meanwhile is appalled that her mother has taken to dressing plainly and working with their serfs. Lady Anne has promoted Thaddeus to the role of steward and Eleanor does not feel he pays her the respect she considers her due. Believing herself above common law she seeks out vile entertainments.

Beyond Develish, villages are being wiped out by death or abandonment. Travellers pose a danger as food is scarce and symptoms of the plague take days to show. There are also lords travelling with their fighting men eager to acquire, by whatever means, anything of value left in the chaos. Lady Anne must use artifice and the loyalty of her people to keep them safe. With each success and acclaim for the brave, Eleanor grows more bitter and unhinged. Lady Anne recognises that they cannot live in this way for long, that some must venture out for news and supplies or her people will starve.

This is a broad, sweeping tale that transports the reader back to a time when few serfs would ever venture beyond the demesne in which they were born. They were property whose purpose was to be worked for the benefit of their lord. Even the gentry were tied to those ranked above them. The church was feared and sickness regarded as punishment. Lady Anne is way ahead of her time in understanding the need for cleanliness and in questioning the edicts of the clergy. She recognises that serfs who survive the plague will be few yet required to till the land. Ownership will, for a time, be in flux.

The various characters’ lives are presented in a manner that is relatable. Differences to today may be great but there are many parallels. The writing is masterful and consistently engaging. The author has lost none of her abilities to enthral her readers.

I have read many fictional accounts of plague ridden England but the breadth and depth of this one truly impressed. It offers more than fictionalised social history, it is high quality entertainment. I am already looking forward to its sequel.

My copy of this book was provided gratis by the publisher, Allen & Unwin.

Author quotes taken from this article: Minette Walters announces first book in decade – and retirement from crime fiction | Books | The Guardian

Advertisements Share this: