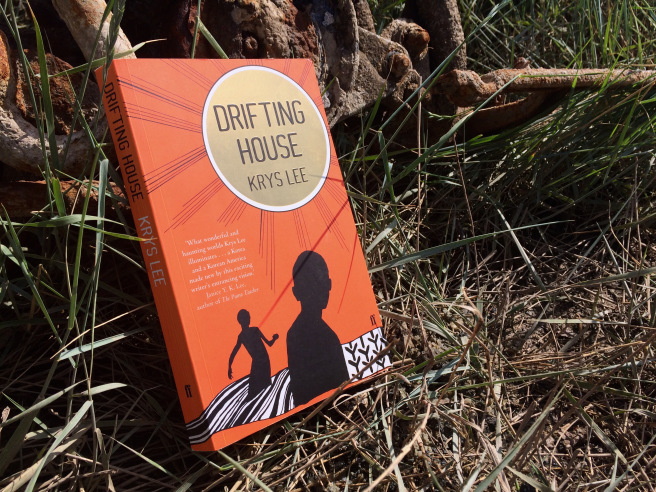

From the mountain springs of Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country and across the Sea of Japan, my Booktrotting journey returns to mainland Asia via the Korean peninsula, with Krys Lee and her short story collection Drifting House.

The day the siblings left to find their mother, snow devoured the northern mining town. Houses loomed like ghosts. The government’s face was everywhere: on the sides of a marooned cart, above the lintel of the gray post office, on placards scattered throughout the surrounding mountains praising the Dear Leader Kim Jong-il. And in the grain sack strapped to the oldest brother Woncheol’s back, their crippled sister, the weight of a few books.

Earlier in the year I read Wells Tower’s Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned, a grim collection of short stories that read like a blacklight shone on the murkier fringes of American society. The book wasn’t entirely to my taste as a reader, but I did think once finished that its focus on race, gender, age and class in the States would have made it perfect for when this Booktrotting tour eventually reaches the USA.

It was a good sign, then, that when I started reading Drifting House—Krys Lee’s debut story collection about modern life on the Korean peninsula—I was immediately reminded of Everything Ravaged. Like Wells Tower, Lee takes a country known for its soaring economy and progressive society, and opts to show none of that; instead, her stories turn to families blasted by domestic violence, women in the grip of oppressive husbands, the laid-off living rough at the foot of luxury high rises. She visits America too, where once well-off immigrants from Seoul are pressed into cramped Koreatown apartments, and even takes one story across the Demilitarised Zone to follow two North Korean brothers desperately seeking refuge in China.

Seoul by night, Philippe Teuwen / CC BY-SA 2.0

Seoul by night, Philippe Teuwen / CC BY-SA 2.0

As you can imagine, that doesn’t exactly make Drifting House the gentlest of reads. For only nine stories and 210 pages, Lee creates an awful lot of truly unsettling scenes—one particular standout for me was in the very first story, ‘A Temporary Marriage’, in which a browbeaten divorcee tracking down her abusive ex-husband in Los Angeles braces herself expectantly for a beating when she angers the man with whom she is staying.

But as awful as the actual events of these episodes are, it’s Lee’s writing (in the best possible way) that really drives home the discomfort. Compared with Wells Tower, whose gritty style often balloons into pure shock value, Lee never appears to revel in what her characters do; instead, she narrates their actions almost matter-of-factly, as if torn somewhere on the line between abhorrence and sympathy. She suggests that her characters aren’t inherently bullies, thieves and murderers, but are gradually made more capable of committing vile acts by the harshness of what surrounds them: in the final story, ‘Beautiful Women’, Lee writes “here, boys blow up a frog to see how many pieces are created. There is a camaraderie in robbing small shops at knife-point. Men beat up their wives, their wives beat their children, the children beat their friends.” With the lengths to which Lee goes to understand her characters’ motivations, even their vilest actions are made somehow human—and all the more frightening for that.

View from Busan Tower, Iwy / CC-BY-2.0

View from Busan Tower, Iwy / CC-BY-2.0

I can’t say I was that surprised to find conflict forming such a key theme in Drifting House. From what I already knew of Korea’s history (chiefly the Korean war of the 1950s and the peninsula’s prior occupation by Imperial Japan) I was expecting some elements of that violent past to still be present in Lee’s stories—much like how the many guerrilla and revolutionary wars of Latin America weighed heavily on my Booktrotting reads there.

But what did surprise me was how much of Drifting House‘s conflicts centred around personal issues, such as family relationships and in particular the treatment of women in Korean society.

Historically, thanks in large part to the teachings of Chinese philosopher Confucius, the lives of Korean women centred around little more than domesticity. Access to formal education was rare and basic legal rights sparse, and for the most part young Korean girls were raised with deference and subordination to their future husbands in mind. Officially, that all changed after the Second World War, when South Korea’s 1948 constitution ruled all citizens equal before the law and free from discrimination; since the late 1980s especially the south’s government has been pushing to address gender inequality, starting with a series of employment and welfare acts designed to level the legal standing between men and women.

But according to Krys Lee and Drifting House, whilst Korean women may have legislative equality, their social status is still very much dictated by patriarchal traditions. The female characters in Lee’s stories are often educated, working, even wealthy, but none of that counts for them when it comes to demands to obey their fathers and husbands, or keep a respectable house. And when those demands aren’t met, all too often the response is force and intimidation; the result, unhappiness and pain.

Koreatown, NYC, Ingfbruno / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Koreatown, NYC, Ingfbruno / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Up next, my Booktrotting tour will cross the North Korean border into China, and join Yiyun Li’s short story collection, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers.

Advertisements Share this:- Share