David Michael Newstead.

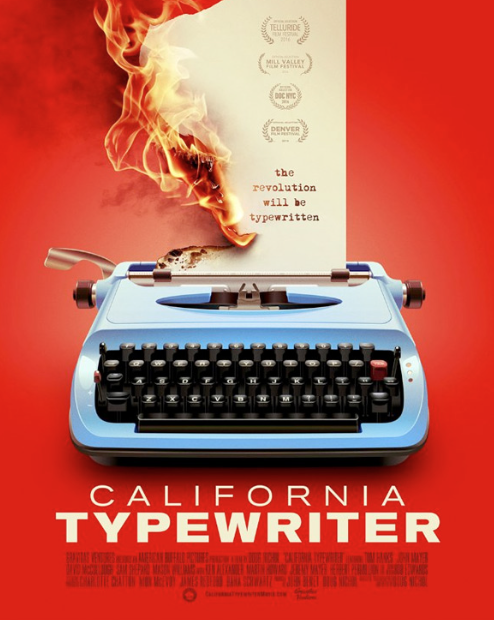

California Typewriter pretends to be a documentary about typewriters, but it’s actually about the limits of technology in our lives. The Revenge of Analog is a book by David Sax about outdated things that have found success again in the digital age precisely because they aren’t digital. I didn’t intend to read that book right after I saw the documentary. It was just by chance. The documentary got put on Amazon Video and then I finally got around to reading something that had been sitting on my bookshelf. As it turns out though, the two go together perfectly.

California Typewriter follows a range of people and their connections to typewriters today. Actor Tom Hanks collects typewriters for fun. Musician John Mayer uses them to write songs. Artist Jeremy Mayer builds elaborate sculptures out of old typewriter parts for Silicon Valley executives. Meanwhile, a small brick and mortar store in Berkley still sells and repairs typewriters and struggles to stay afloat. It’s through these stories and others that some important issues get raised about technological change and obsolescence, the significance of actual tactile experiences, and the need for more balance in our relationship with technology. For me, one of the most memorable parts was when John Mayer talked about digital technology and the cloud as being a kind of glorified trashcan where you can go back and look at everything you’ve ever done, but you never actually do. Another great moment came when a historian explained that all the letters of the word typewriter are located on the top line of your keyboard and were put there intentionally so that salesmen could demonstrate this “high-tech” new product.

The Revenge of Analog follows the revival of industries and activities that seemed like they were near death just a few years ago. In a purely utilitarian sense, most of the things David Sax covers in the book were made obsolete by digital technology and the internet. Yet, they survive and are now thriving, because people want more than just the internet! Some notable examples include the dramatic resurgence of vinyl record sales, the success of companies like Moleskine and The Economist, and people’s renewed love of board games at a time when meaningful interactions are becoming scarcer and scarcer. But instead of this reflecting some hipster trend or baby boomers’ nostalgia, Sax shows the limits of technology’s dominance where people choose an analog option because they actually prefer it. He goes on to discuss the dismal results of some digital initiatives like MOOCs (Mass Open Online Courses) and One Laptop Per Child that were supposedly going to be so world changing. They weren’t. The author writes:

Digital’s overwhelming superiority initially renders the analog alternative largely worthless, and devalues that analog technology significantly. But over time, that perception of value shifts. The honeymoon with a particular digital technology inevitably ends, and when it does, we are more readily able to judge its true merits and shortcomings. In many cases, an older analog tool or approach simply works better. Its inherent inefficiency grows coveted; its weakness becomes a renewed strength.

On page 40, he later adds:

Then there is the question of legacy. In digital, a legacy brand is yesterday’s lunch, because the best digital technology is always the next one, and consumers have no loyalty to the past. In analog, legacy commands a premium. “You can perfectly imitate a Louis Vuitton bag,” Maffe said, pointing at one hanging on the arm of an elegantly dressed woman sitting near us in the luxury hotel café where we were having coffee, “but you can’t sell it for six thousand dollars because you don’t have the heritage. As long as you can convince users the past is relevant, they’ll pay billions for it. There is no rational economic reason behind that. Just marketing.”

I spent some time mulling over this book and the documentary I had watched. Neither one was anti-technology by any means. It’s just that we’re at an interesting crossroads as a society – somewhere between The Twilight Zone and Black Mirror. So if it’s possible to do absolutely everything online, then I think it’s noteworthy when we choose to take a different path. For many people, that doesn’t come naturally, because embracing new technology and discarding old devices was our default for so long. I’m part of a shrinking group that can vaguely recall life before the internet. I remember all the upbeat technological hype of the late 1990s and 2000s. And while plenty of those changes were good, it’s also important to question the extent of technology’s place in our lives nowadays. Or perhaps a better way of saying it: deciding what we want to keep in the real, non-digital world.

David Sax also points out how we value the analog, the real, and the tangible in ways that the digital can’t ever come close to. Nostalgia might play a part in that, but it’s not the driving force anymore. To me, it almost seems like every platform or medium has its own golden age that can be remembered and romanticized, but never quite recreated. After all, radio will never be as relevant as it was when FDR was giving fireside chats or when Orson Welles was dramatizing The War of the Worlds. To people of a certain generation, cassette mix tapes on a Sony Walkman were like love letters. And comic books were once the cheap, brightly colored foundation of many people’s childhoods. Polaroids, paperbacks, movie reels, 8-tracks, newspapers, Saturday morning cartoons: it all meant something to someone. And when I try to recall my own memories of these analog things, it feels like a time capsule that’s meaningful to me, but would probably be inconsequential to someone who grew up in another era. I remember the first CDs I bought and how I eventually alphabetized them all on this rotating plastic rack. I remember the thrill when my family first got a VCR and how fun it was to rent VHS tapes from Blockbuster on a Friday night. I remember being hunched over my desk as I wrote down ideas in Mead composition notebooks that could fill up a shelf. And I remember fondly waiting a week or more for photos to get developed before I knew how a picture turned out. I liked those things and I value those memories. Hell, I own a typewriter. But The Revenge of Analog and California Typewriter aren’t trying to turn the clock back a few decades to some idyllic past. They’re really about living in the moment and nowadays that means not being online all the time.

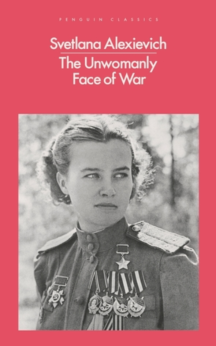

Watch California Typewriter

Read The Revenge of Analog

Previous Installment

Advertisements Share this: