While we were traveling America last year, we came across Vol 3 of Larry Gonick’s fantastic ‘Cartoon History of the Universe’ series. Endorsed by everyone from Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau to the late Carl Sagan, the series more than lived up to the hype. This led us to his website whose work spans topics ranging from history to physics to pure math.

That’s how we found out that since the very beginning, Larry has seen comics as a way not only to entertain and inform, but to change the world we live in. Once we’d seen that, we knew we had to interview him. Thankfully, he obliged.

Larry Gonick

1) How did you get into reading comics? What was the first comic you ever owned?

My father used to read me the comic strips from the Sunday Denver Post when I was four years old. I’ve been reading comics ever since. I couldn’t possibly remember my first. I’m pretty sure I Go Pogo entered the house by the time I was six. Kelly was surely my strongest stylistic influence.

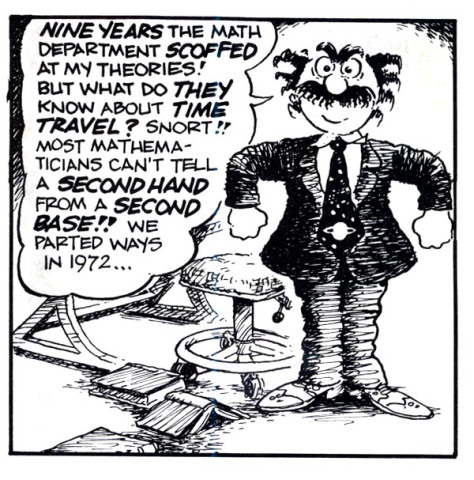

Five years earlier, when I was applying to grad school, I had a sort of existential crisis. I suddenly realized that I was marching along a path leading to a career in a math department, without ever consciously having decided to walk that path. It was a chilling sensation, a sort of claustrophobic response to an intellectual realization about how futures are made. At that point, though, I saw no alternative, so grad school it was. Later, with social change erupting all around, a friend brought me a proposal to do a comic book on tax reform, inspired by the political-education/propaganda comics of Rius in Mexico. Rius (Los Agachados, Cuba for Beginners) was an eye-opener. He may not be the first, but he’s by far the greatest cartoonist to use comics to inform rather than simply to satirize. A soon as we started working, I was hooked.2) On your website, it says you dropped out of math in 1972. What’s the story there?

The key for me was this: although I drew a lot, I had zero confidence that my brain alone could generate enough comic inspiration to last a lifetime—until I saw this use of the medium. Here, I realized, was an endless source of material, and that’s how it’s turned out. When I got my first weekly comic strip, pathetically paid though it was, I dropped out of grad school.

The key for me was this: although I drew a lot, I had zero confidence that my brain alone could generate enough comic inspiration to last a lifetime—until I saw this use of the medium. Here, I realized, was an endless source of material, and that’s how it’s turned out. When I got my first weekly comic strip, pathetically paid though it was, I dropped out of grad school.

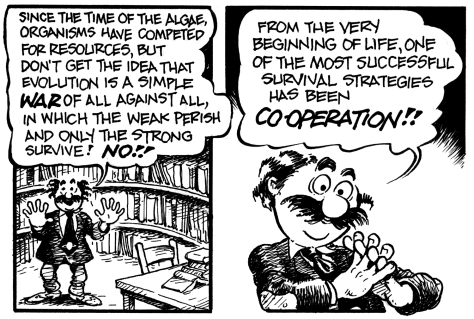

3) You also say that “My crazy hope is that this crazy medium will somehow improve this crazy world.” That describes our work pretty well, too. But you’ve been doing this since the 70s. What made you think comics were a good medium for social change?It’s hard to say. In the absence of a movement, not much. In the presence of a movement, plenty. I once (around 1975) had this argument with Jules Feiffer. I maintained that cartooning could work in support of a social movement (or even a political party). He insisted that the artist has to maintain independent judgment. At this point, I’d like to think that both are true, to some extent. It’s a rare social movement that doesn’t develop its own load of cant and shibboleths, and though the artist may support the movement’s goals and principles, she or he will have an overwhelming internal urge to make fun of the bullshit. It’s complicated!

4) Your background is in math, but your bibliography covers an incredible diversity of topics from history to chemistry to sex! Did you have co-authors for some of those titles, or did you research it all as you went along?

I had co-authors for all the science titles but one. I did the math books myself and found them tough going, because I’m so far removed from the classroom. My collaborators, being teachers, all had a good sense of what students find easy and hard, whereas I felt myself groping straight through. And the collaborations, despite occasional struggles, have always been a great experience for me. I learn a lot, and I like to think that my relentless cross-examination can lead the scientists to a little rethinking, too.

History I did all myself. For 35 years, I read almost nothing but history and biography. I love the stuff.

I had co-authors for all the science titles but one. I did the math books myself and found them tough going, because I’m so far removed from the classroom. My collaborators, being teachers, all had a good sense of what students find easy and hard, whereas I felt myself groping straight through. And the collaborations, despite occasional struggles, have always been a great experience for me. I learn a lot, and I like to think that my relentless cross-examination can lead the scientists to a little rethinking, too.

History I did all myself. For 35 years, I read almost nothing but history and biography. I love the stuff.

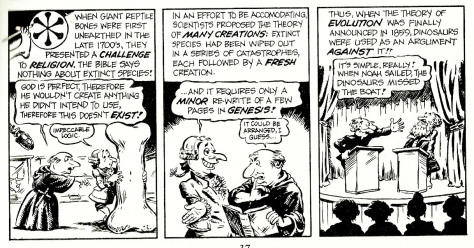

5) Something that really stood out to me when I was reading the first three volumes of ‘Cartoon History of the Universe’ was how deliberately you avoided falling into a Eurocentric narrative of history. The Islamic world, the Indian subcontinent and China all feature prominently in your account of world history, with attention paid to the Eurasian steppe and sub-Saharan Africa as well.This was a conscious decision, obviously. My original political impulses made me mistrust traditional approaches and seek new narratives and connections, and believe me, they were easy to find.

But in Vol 4 (rebranded by the publisher as Cartoon History of the Modern World, Vol 1) the focus shifts dramatically to Europeans, apart from a good account of Meso-American civilization and some coverage of the Inca. There’s still some coverage, but it isn’t at the level of the previous books. Why was that?That’s where the narrative leads. The European conquests in America, Africa, and Asia led to European domination of world politics. In retrospect, I may have included too much European dynastic stuff, but the religious wars certainly mattered, and the story of the United Provinces of the Netherlands has been too little told.

6) I know you’ve just finished a book, and there’s a question about that coming up. But do you have plans for any future ‘Cartoon History’ or ‘Cartoon Guide’ titles, or anything else?

I’m in the middle of The Cartoon Guide to Biology with Dave Wessner, a biology professor at Davidson College (Steph Curry’s alma mater. Go Warriors!). It will surely be the longest of all the science books. I’m also working on my first project explicitly meant for the classroom: a large series of quiz questions for beginning physics.

7) Looking at your website led me to the ‘Commoners’ series, which I read as short comics about the enclosure of different commons by transnational corporations. What led you to produce those?

An old friend and associate, the late Jonathan Rowe, who spent his life in activist writing, put me on to the idea and found some funding to support the strip.

8) Do you still make time to read comics? Have you read anything good lately?

I have the time to do it but little inclination. I mostly read novels, with a little non-fiction on the side. My problem with graphic novels is that they’re quick to read and you rarely want to go back. In this, they’re different from the great comic tradition of work like Pogo, which I re-read until all the pages fell out. I’m proud to say that the Cartoon Histories are books that people return to again and again. I realize this sounds dismissive, and in fact I still read comics. I love Kate Beaton’s Hark! A Vagrant and check in with Randy Monroe’s xkcd pretty often. Of more-or-less recent book-length pieces, my favorite by was Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

9) You’ve got a new book coming out in the winter: “Hypercapitalism?” Can you tell us a little bit about it? What moved you to write it?

Tim Kasser, a psychology professor at Knox College, approached me about doing a book on capitalism and responses to it. I thought, Hm, why not go back to my political roots? The time was right. I especially liked approaching the subject from an unconventional direction: the psychology of money-chasing and material gain and what it does to more humane values and pursuits like community feeling and care for the planet’s future. Tim insisted that we finish the book with a long section on what people are actually doing to address our out-of-whack values, and I’m hoping that the book will stimulate some productive discussion out there in the discussion-sphere.

10) Inevitably, interviewers miss an important question. If there’s a question you wish I’d asked but didn’t, feel free to pose it yourself and answer it here.

Q. What’s your Social Security Number, Larry? A. I prefer to remain a man of mystery.

Advertisements Share this: